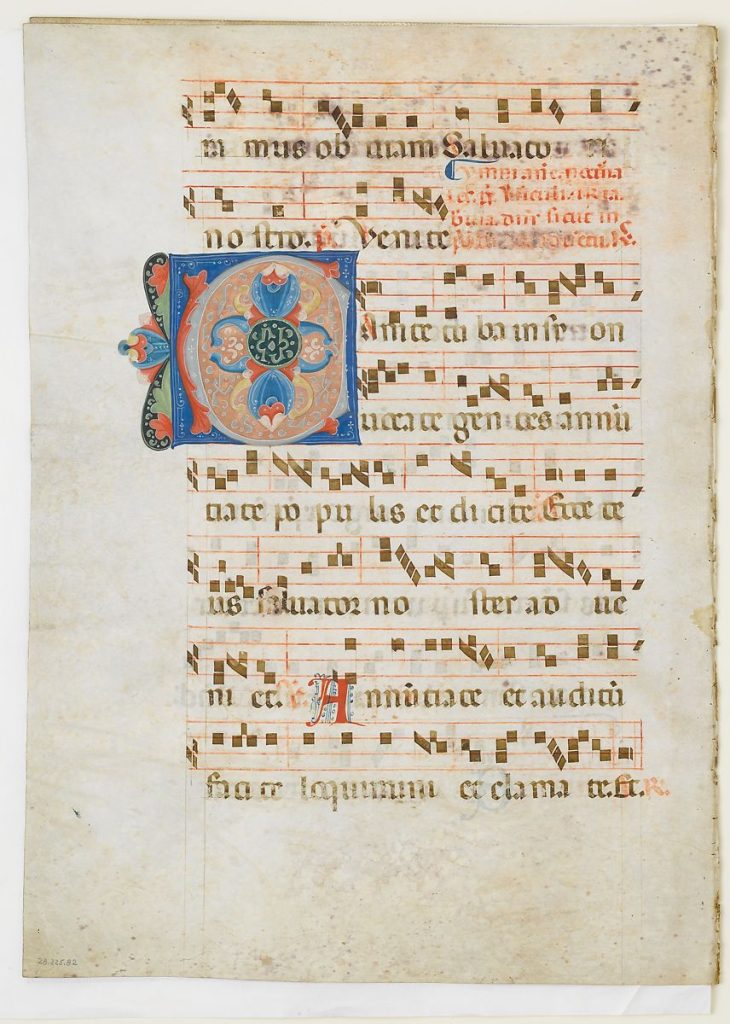

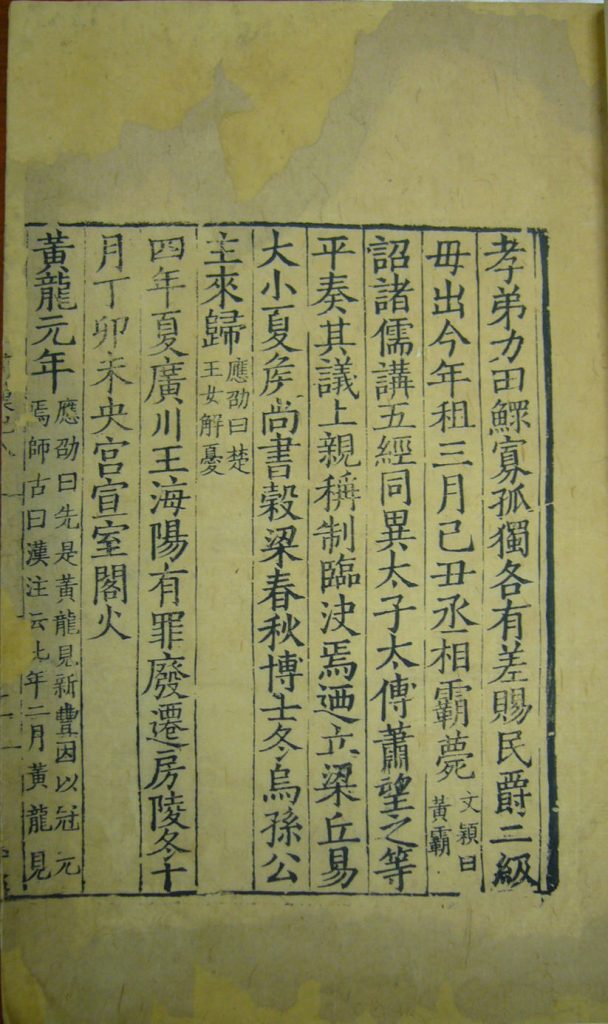

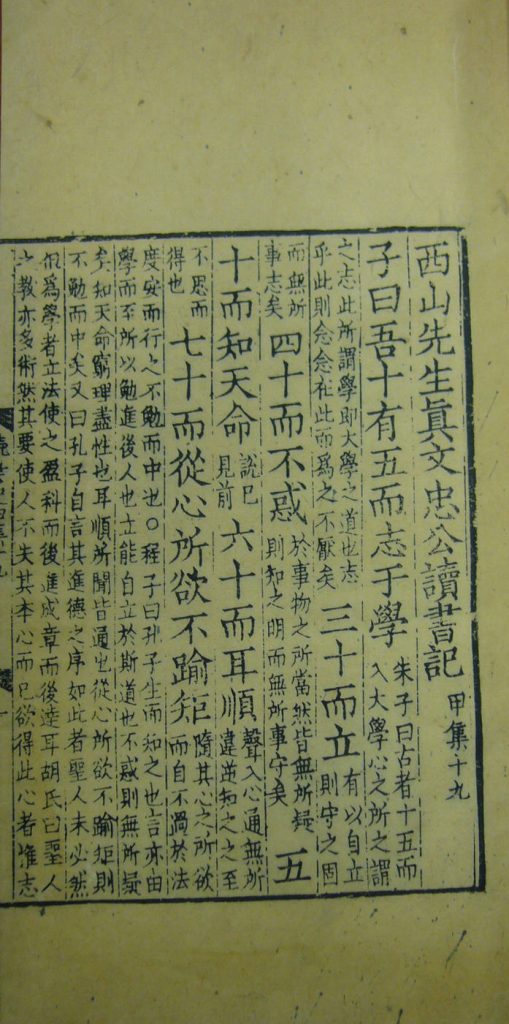

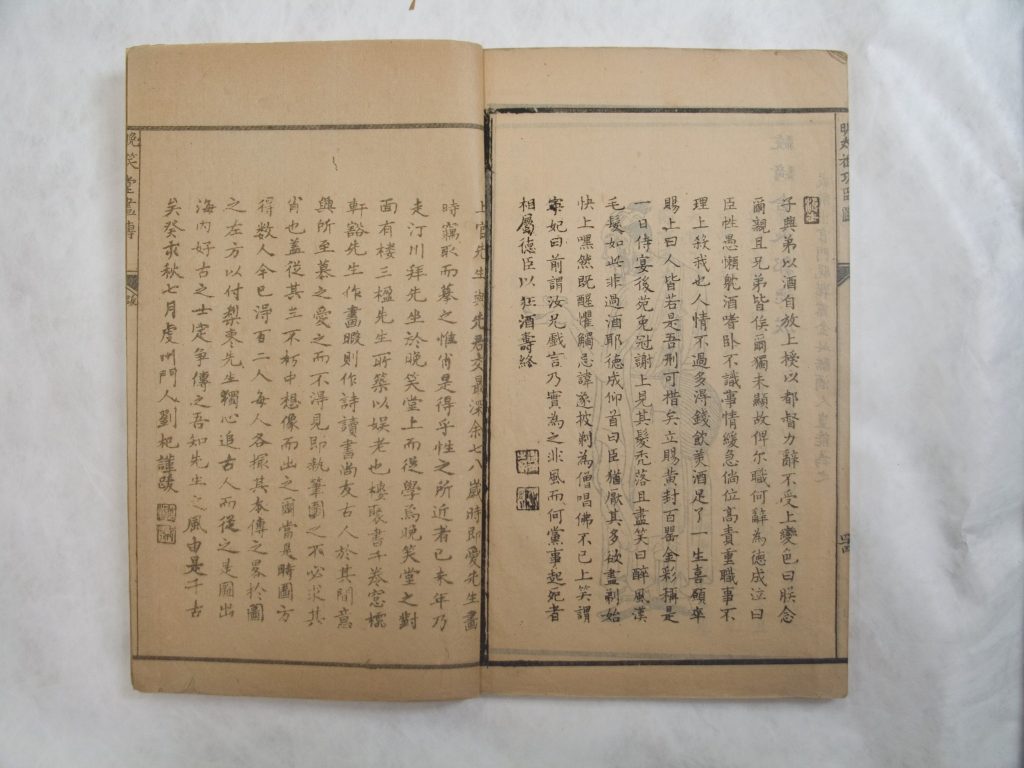

Modern craftsman carving wooden block print - http://www.seeyangzhou.com/2019-11/18/c_425092.htmPrintmaking in China was started around the seventh or eighth century with the creation of xylography, the art of wood carving. Originally, Chinese printmaking was made to spread Buddhist script, but was later adopted by commercial publishers and the state. Early Chinese printmaking flourished thanks to the government of the Song dynasty (960-12766). The Song dynasty government funded printing projects for Confucian classics and the civil service examinations. These exams were important in Song culture, as a means to climb the social ladder through literacy and education.

The printing press used cheap material and labor, since literacy was not required for wood carving. In comparison to the Gutenberg printing press (1450) where the initial investment was more expensive for the metal material and labor, the low investment price for Chinese printing allowed for an increased variety and abundance of books and genres. Chinese genres included: medical manuals, almanacs, calendars, dictionaries, and more. Although it is important to note the speed and quantity at which the Gutenberg printing press was created was greater than the early Chinese printing press.

Another key difference is that moveable script was not popularly used in China, although it was invented by Bi Sheng in the 11th century. Bi Sheng’s moveable type was made out of delicate porcelain. A later rendition of the moveable type was made of small wooden blocks by Wang Zhen. Korea later added on to this technology with metal casted moveable type in the early 1200’s. The moveable script was not popular because it was expensive to produce. In comparison to Romanized script, Chinese script had thousands of characters that would need to be made for a single set. The great amount of characters needed to be made to start the Chinese printing press was most likely much higher simply because of the thousand more characters needed to be made.

Why was Gutenberg credited for the printing press when printmaking started in China centuries before Europe?

It can be argued that Gutenberg gets credit for the invention of the printing press because of the innovative speed, quantity, and widespread use. Meanwhile, the Chinese printing press preferred traditional xylography because of the extensive character count and high expense of moveable print. Though East Asia did create moveable text before 1450, the lack of use could account for the lack of credit.

Continue reading “Before the Gutenberg Printing Press”