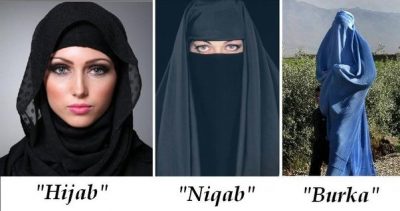

When I was thirteen years old, I presented a self-written and researched speech to over one hundred people titled “The Rights of Women in Islamic Countries.” The speech opened with a translated verse from the Quran: “And say to the believing women that they should lower their gaze and guard their modesty; that they should not display their beauty…” The speech focused on the Niqab and the Burka as symbols of female oppression. I won second place for my speech in the final round.

When I was thirteen years old, I hadn’t yet learned the concept of cultural relativism or of ethnocentrism.

I was right, they were wrong, and they needed help.

Approaching the issue of women’s oppression in Islam with cultural relativism is imperative; while veiling might be degrading to me, to my Muslim sister veiling might be the paramount symbol of modesty.

The first person who encouraged me to approach this issue from a different perspective was an ex-boyfriend when I was eighteen years old. Ali, an Iranian-born, Canadian-raised, non-practicing Muslim, explained his perceived “pros” of the legally-enforced head scarf for women in Iran:

[paraphrased] In Western culture, women are taught to dress and act to appease men sexually. The opposite is true in Iran. In Canada, women are hyper-sexualized, as evident by the bombardment of images of nearly-naked women in the media, and the clear correlation between a woman’s popularity and her promiscuity or provocativeness (think Kim Kardashian – infamous for a sex tape and for the sexualization of her body). In Iran, the veil protects women from this exploitation and depravity. In Iran, women are not forced to sexually compete for men as they do in the West, rather, this is thought of as grossly immoral.

There were three clear flaws that I recognized in Ali’s argument: (1) his overgeneralizing of women in Western culture, (2) his lack of recognition for the idea of choice of dress – something that I have, and that women living under the forced implementation of any coverings do not, and (3) simply because one culture is oppressive to women because it encourages their sexualization, does not mean that another culture that forbids public spectacles of female sexualization is not oppressive.

It is easy then to assert all coverings that are enforced through legal, religious, and violent means are not just a symbol of female oppression but an overt instrument of female oppression. Let ‘oppression’ here be defined as the exercise of control over women by men, through sexist laws and or violence in any given culture.

The problem with this argument is of course that coverings are not forced unto all Muslim women, and that there exist multitudes of Muslim women who elect to wear some form of covering.

However, despite these sect-culture counterexamples of Muslim women who have choice, there exists overwhelming anti-female rhetoric in Islam, which is exemplified by the disproportionate amount of violence against Muslim women by Muslim men.

It is clear then that the issue of female oppression in Islam does not exist simply within, for example, a hijab, but rather within the patriarchal culture that defends and encourages the systematic oppression of women with religious doctrine. The issue of the veil, or other coverings, is then irrelevant, and discussions of the oppression of women in Islam should be more focused on reforming the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes.

Whether Muslim women need saving is up to Muslim women; as the best advocate for Muslim women is Muslim women themselves.

Food for thought…

In a report, the Canadian Council of Muslim Women stated: “Since, for Muslims, the Qur’an is God’s word, the pervasive view is that God ‘himself’ gives men the license to control or ill-treat women.” Does this statement assert that all Muslims, men and women, are inherently anti-feminist?

Here’s a full version of the film Osama:

This film inspired my ongoing curiosity about the issue of women’s rights in Islamic countries. The film follows a mother and daughter through their tribulations under Taliban rule in Afghanistan.