by Lauren Fitschen

The level of emotional maturity in kindergarteners is evaluated based on scores within four different sub-scales: prosocial and helping behaviours, aggressive behaviours, hyperactive and inattentive behaviours, and anxious and fearful behaviours. There are many different factors that can contribute to why a child may develop a vulnerability within areas of their development, in this case, emotional maturity. The environment that the child is exposed to has a significant impact on their emotional development. Exposure to violence, the impacts of poverty, caregivers not meeting the child’s emotional needs, or being raised in a household where caregivers around them are unable to regulate their own emotions and therefore are unable to demonstrate healthy emotions, are all examples of environmental impacts that will impact a child’s ability to regulate their emotions and affect development. Epigenetics refers to the relationship between genetics and the environment, and how a combination of those two factors contribute to one’s development (Berk, 2021). Pertinent environmental exposures are actually able to interact in a way that alters gene expression in an individual, and this alteration can be passed down through generations. A child growing up with developmental vulnerabilities may be experiencing the effects of negative epigenetic modifications from generations past that can impact the child’s resiliency against adversities. Resiliency in this case refers to the child’s ability to adapt and adjust when faced with a threat to their development. We can help children counter these negative epigenetic modifications by building up their resiliency through carefully designed interventions (Berk, 2021).

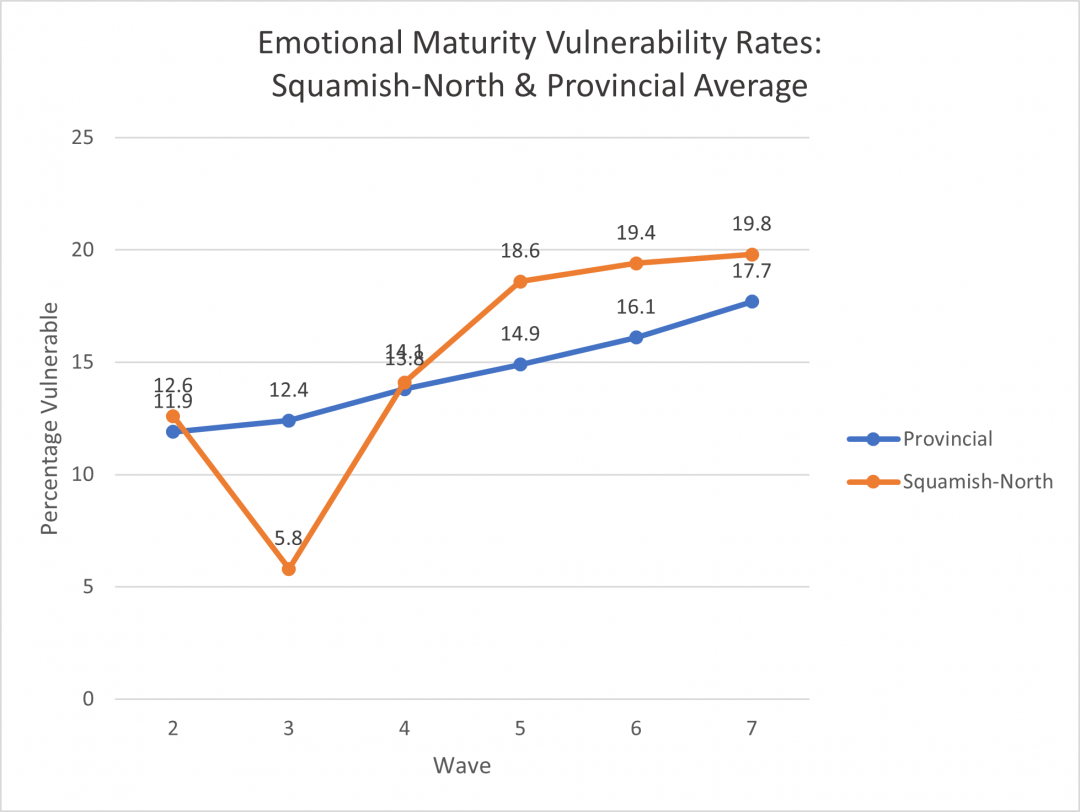

The University of British Columbia (UBC)’s Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP) has been using the Early Development Instrument (EDI) to collect data on child development. Data published from HELP’s EDI Wave 2 (2004-07) to Wave 7 (2016-19) were used to create the graph in Figure 1 below, comparing rates of children presenting with emotional vulnerabilities in Squamish-North vs the provincial average. The children of Squamish-North are 2.1% above the provincial average as of Wave 7.

The children reflected in the Figure 1 data above may display a variety of behaviours from the aforementioned four emotional maturity sub-scales. Behaviours such as, frequent crying, separation anxiety, sad/depressed disposition, difficulty sitting still or fidgety, easily distracted, difficulty following directions, temper tantrums, disobedience, taking belongings from others, bullying, and physical fighting (HELP, 2019) are common among children that struggle with emotional maturity and in particular self-regulation. 1 in 5 children in the Squamish-North neighbourhood are entering kindergarten with vulnerabilities in emotional maturity, and without help, many of these children will continue to struggle with this area of development throughout their lives. Second Step Early Learning Program (SSEL), is a short-term intervention (28 weeks) that builds resiliency in children by helping children develop long-term self-regulation skills (Committee for Children 2011, as cited in Alfonso & DuPaul, 2020), treating the three subscales: anxious & fearful behaviours, hyperactive & inattentive behaviours, and aggressive behaviours. The Second Step Early Learning Program involves short lessons (7-8 min) administered by teachers. The curriculum focuses on impulse control, “socially just decision-making”, and general social skills (Alfonso & DuPaul, 2020). Studies demonstrate an improvements in behavioural inhibition, cognitive control, task persistence, decision making, and in critical self-regulatory abilities that resulted in better social interactions between adults and peers (Blair & Raver, 2015; Razza et al., 2012, as cited in Alfonso & DuPaul, 2020). With the implementation of evidence-based short-term interventions like the SSEL, it is possible that we will avoid the need for more serious interventions in the future for these children as they grow.

References

Alfonso, V. C., & DuPaul, G. (2020). Healthy Development in Young Children: Evidence-Based Interventions for Early Education. American Psychological Association.

Berk, L. E. (2021). Infants and Children: Prenatal Through Middle Childhood (9th ed.). Pearson.

Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2015). School readiness and self-regulation: a developmental psychobiological approach. Annual review psychology, 66, 711-731. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814015221

Committee for Children (2011). Second Step Learning.

Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP). EDI BC. EDI Waves 2-7 (SD,LHA,NH,BC). November 2021.

Human Early Learning Partnership (HELP) (2019). Early Developmental Instrument 2019. EDI BC. 2016-2019 Wave 7 provincial report. http://earlylearning.ubc.ca/media/edibc_wave7_2019_provincialreport.pdf

Razza, R. A., Martin, A., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2012). The Implications of early attentional regulation for school success among low-income children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 33(6), 311-319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2012.07.005

December 17, 2021 at 12:47 pm

Hi Lauren, thanks for sharing! It is quite concerning to read that there has been a rise in at risk children in the context of emotional maturity development. Reading that the Squamish-North area was above the provincial average was also concerning. I really enjoyed the solutions and possible interventions you came up with though to address these concerns. Great read!