by Aiden Macklin

The Data

While researching the relationship between “Stress” and “Mood or Anxiety Disorder Diagnosis” among low income areas in the Vancouver region, I noticed a stark contrast between the two lowest earning areas; Strathcona and Victoria-Fraserview. Despite being comparable in terms of income, they are polar opposites regarding mood disorder diagnosis. Strathcona has an average mood disorder diagnosis of 26%, the highest out of the Vancouver areas. Conversely, Victoria-Fraserview has an average mood disorder diagnosis of 9% (My Health My Community, 2014). But what does Victoria-Fraserview have that accounts for this significantly lower mood disorder diagnosis? Upon comparing the data regarding ethnicity, I may have found an answer.

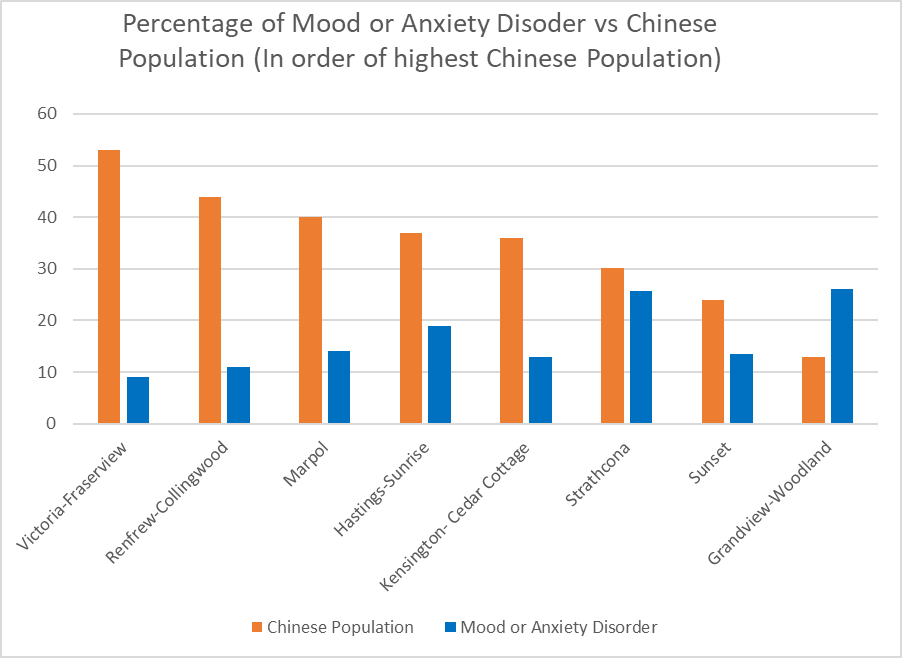

Victoria-Fraserview has the highest Chinese (53%) to Caucasian (23%) population difference when compared to any other region (My Health My Community, 2014). To verify whether there’s a correlation between mood disorder diagnosis and the Chinese population, I created a graph comparing these two variables using the eight lowest income areas in Vancouver, Strathcona and Victoria-Fraserview included.

With the exception of Sunset and Kensington-Cedar Cottage, the higher the Chinese population (orange) is in a given area, the lower the diagnosis is for a mood or anxiety disorders (blue). This is particularly emphasized when comparing the ends of the spectrum, in this case being Victoria-Fraserview and Grandview-Woodland.

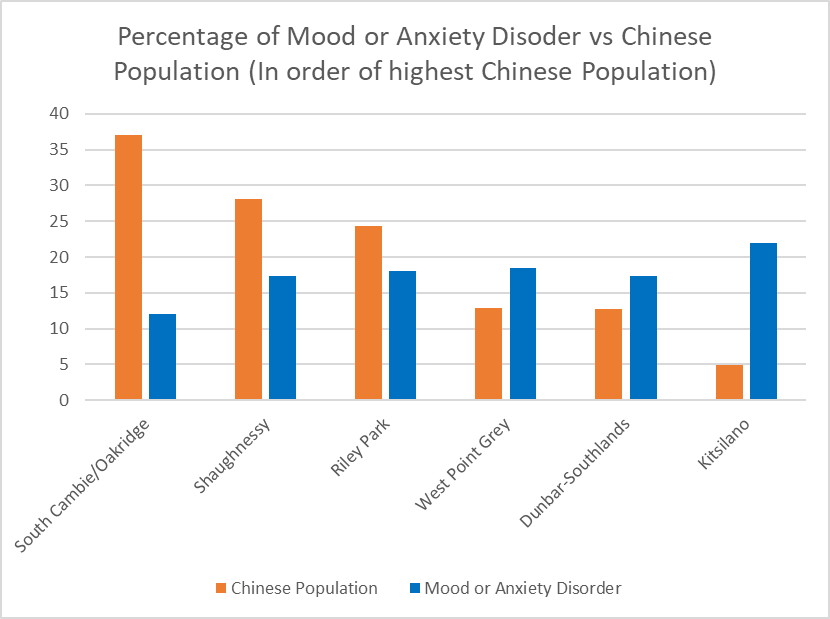

Yet this phenomenon isn’t unique to low-income areas.

This second graph compares the six wealthiest areas in the Vancouver region. As demonstrated with the low-income areas, the greater the Chinese representation in a population, the lower the reportability of mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis tends to be.

This then raises the question; Why is the Chinese population underrepresented regarding mood or anxiety disorder diagnosis? Are they simply less likely to experience a mood or anxiety disorder, or are there other factors preventing them from receiving a diagnosis?

Cultural Sensitivity Surrounding Mental Illness

Based on the research, it’s doubtful that the Chinese population of the Vancouver region are less likely to experience a mood or anxiety disorder. Instead, this discrepancy is likely due to the interaction between Chinese and Canadian culture, within the framework of mental health. The “western” method of mental health typically involves interacting with some variety of health care professional, who then provides a diagnosis based on the symptoms that the patient experiences. While this methodology may seem reasonable, there are a number of problems that can prevent Chinese individuals from receiving a diagnosis.

Perhaps the most obvious of these problems is the language barrier. Studies have shown that as many as 80% of older Chinese adults living in Canada exclusively spoke Chinese when at home. Furthermore, the language barrier has been reported as a risk factor for the underutilization of mental health services (Tieu & Konnert, 2014).

Typically, the first step to receiving a diagnosis for a mental illness is communicating that you’re experiencing symptoms. While this prosect may seem embarrassing for some, this hurdle can be quite problematic for a Chinese individual. Within Chinese culture there is the concept of Guanxi, which represents the personalized network of relationships that exchange support, resources and benefits. An important part of Guanxi is to preserve the family’s “face”, which is done by each family member upholding their reputation as a good and moral human (Chen et al., 2013). Unfortunately, this often comes at the expense of individuals that experience mental illness, who are often stereotyped as having unpredictability, incompetence, and a failure to achieve full moral standing in adulthood. Further issues arise when exclusively looking at the older Chinese population. Research indicates that the 65+ Chinese demographic is less able to correctly identify depression, more likely to favour traditional Chinese remedies over psychiatric services, and to attribute traits of depression to failures of character, rather than as a medical problem (Tieu et al., 2010).

Chinese culture, and its values that include Guanxi, fall under the umbrella of the “Collectivist Culture.” These cultures, when compared to individualistic cultures, tend to value compliance to the social norm, interdependence, and group harmony. Because symptoms of mental illness typically fall outside the social norm, it is subsequently devalued and stigmatized (Papadopoulos et al., 2012).

The Chinese demographic probably isn’t exceptionally resistant to mood or anxiety disorders. Instead, they may just not feel as comfortable as other ethnic groups to disclose mental health problems due to cultural norms and expectations. Or, in the case of older adults, a lack of understanding as to how we define and treat mood disorders, which is further compounded by language barriers.

References

Chen, Lai, G. Y.-C., & Yang, L. (2013). Mental illness disclosure in Chinese immigrant communities. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032620

Papadopoulos, C., Foster, J., & Caldwell, K. (2012). ‘individualism-collectivism’ as an explanatory device for mental illness stigma. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(3), 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-012-9534-x

My Health My Community. (n.d.). My Health My Community Atlas. My Health My Community. Retrieved June 6, 2022, from https://myhealthmycommunity.org/explore-results/results-by-community/dashboard/

Tieu, & Konnert, C. A. (2014). Mental health help-seeking attitudes, utilization, and intentions among older Chinese immigrants in Canada. Aging & Mental Health, 18(2), 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.814104

Tieu, Konnert, C., & Quigley, L. (2018). Psychometric Properties of the Inventory of Attitudes Toward Seeking Mental Health Services (Chinese Version). Canadian Journal on Aging, 37(2), 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980818000041

Tieu, Konnert, C., & Wang, J. (2010). Depression literacy among older Chinese immigrants in Canada: a comparison with a population-based survey. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(8), 1318–1326. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610210001511

Recent Comments