by Leilani Brown

Social competence refers to the students’ ability to interact and work cooperatively with their peers, follow classroom routines and expectations, explore their environments with interest and curiosity, and engage in self-management behaviours (The Five Scales of the EDI: Social Competence, 2019, p. 13). Both environmental and genetic influences affect a child’s social competence development. For example, gene-environment interactions demonstrate that students will respond differently to things that happen in the environment because of their genetic makeup (Berk, 2021). In addition, cultural and gender differences play roles in temperament through gene-environment correlations. For example, strong emotions would be discouraged in cultures where calm and community-minded values are prevalent and encourage behaviours that benefit the group (Berk, 2021). The more relaxed environment promotes a more secure attachment and temperament. Children are more likely to be secure in their attachment and curious, which sets the stage for demonstrating social competence skills.

Risk Factors

Erratic and stimulating environments can contribute to slower cognitive development and aggressive behaviour. Externalizing behaviours would inhibit the child’s ability to cooperate with peers and maintain social-emotional regulation. Gender differences also indicate a genetic component, as they can be observed in infancy (Berk, 2021). Boys are often more active, emotionally expressive, and engage in more risky behaviours. Girls tend to be more compliant and more hesitant. Gender stereotyping also contributes to these behaviours persisting, suggesting a gene-environment correlation.

Protective Factors

Marsten and Barnes (2018) identified some protective factors promoting resilience in children as sensitive and supportive parenting, close relationships and emotional security, motivation to adapt, family flexibility and problem-solving, co-regulation, positive familial roles, positive family outlook, values, family routines, quality schools, and active community participation (p. 6). A healthy and supportive environment can offset genetic risk factors that impede the child’s healthy development and promote resilience. From a social competence perspective, a child’s emotional reactivity and sense of security to explore are essential skills influenced by their genetic makeup, the family environment, and the parent-child relationship.

Burns Lake Demographics

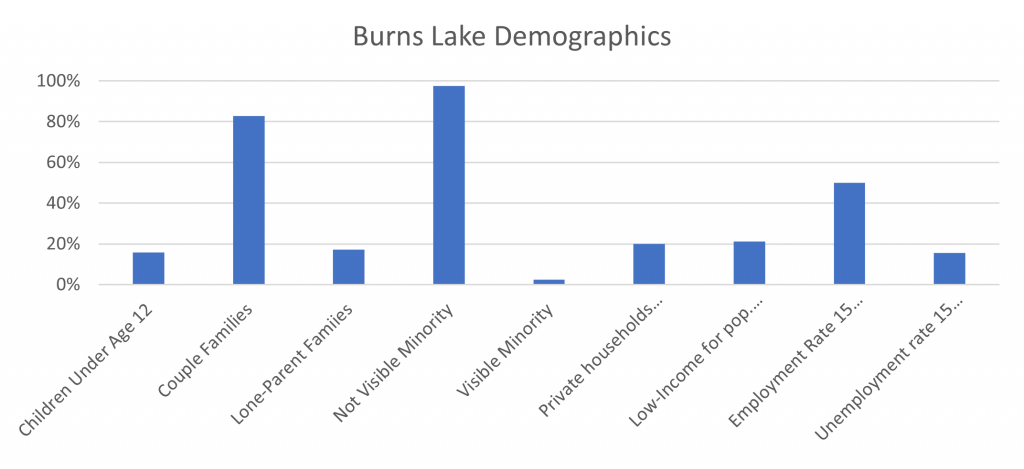

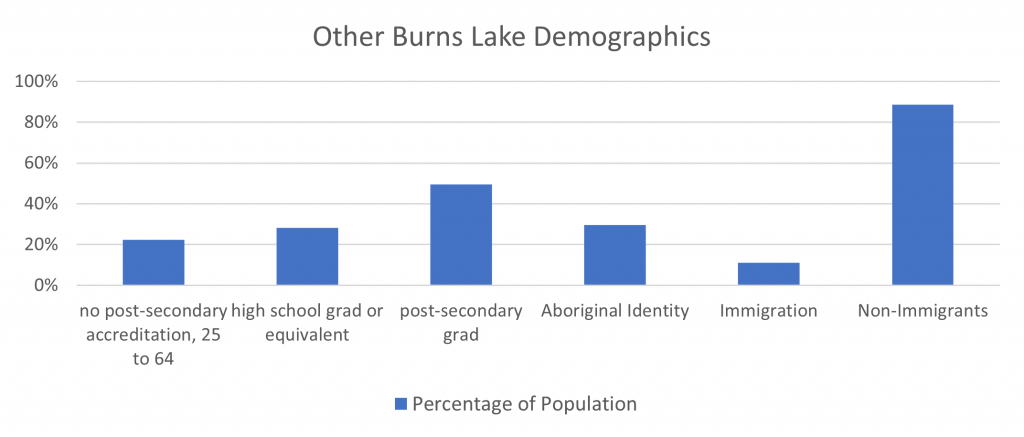

Burns Lake has a small population consisting of primarily non-visible minority people with two-parent households. Almost a quarter of the population is 19 and under (NHS, 2016). The macrosystem of the child and socioeconomic class, living conditions, and employment for caregivers can be indicators that resilience may need to be promoted (Jones et al., 2015). Being a person who is a visible minority could be a factor playing a role in children’s risk levels, as they would be such a small percentage of the population (NHS, 2016).

Nechako Lakes is considered more disadvantaged from a socioeconomic standpoint (p. 36). Cultural differences may be demonstrated as influencing different outcomes from Western upbringing (Berk, 2021). Socioeconomic status can be primarily determined by education level, technical skills and years of job experience, and how much money the caregiver makes through unemployment (Berk, 2021, Socioeconomic Status and Family Functioning, para. 1).

Social Competence Data

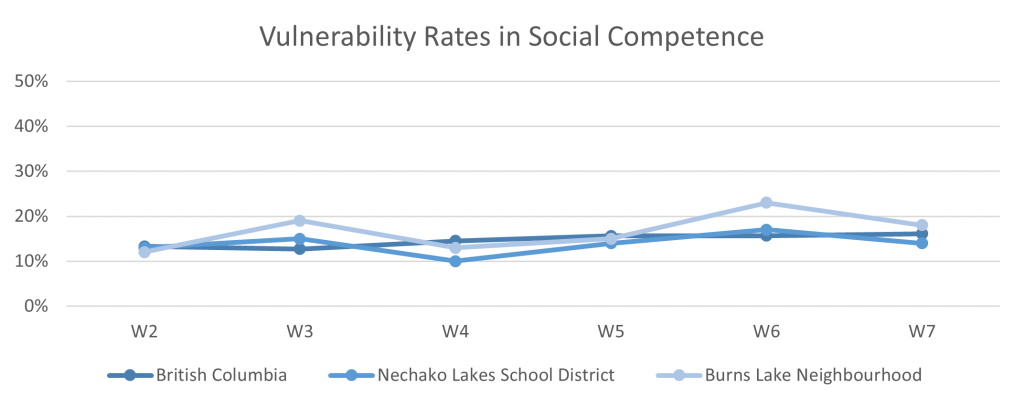

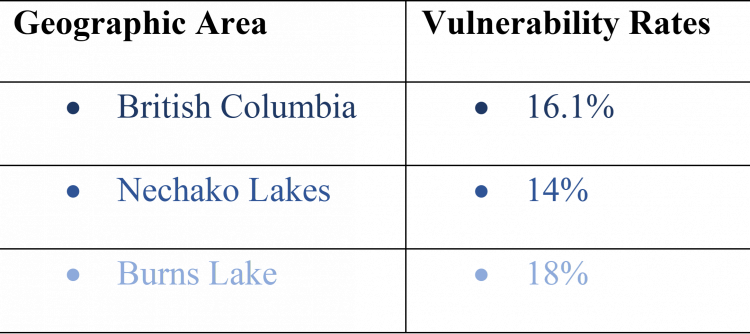

EDI Scale: Social Competence Vulnerability Rates

The provincial average of 16.1% demonstrates that Burns Lake is a neighbourhood at risk for social competence vulnerability. This data suggests a need for interventions to address this neighbourhood’s components negatively impacting the children’s social competence skill development (Wave 7 Community Profile, 2019. Nechako Lakes School District; SD91).

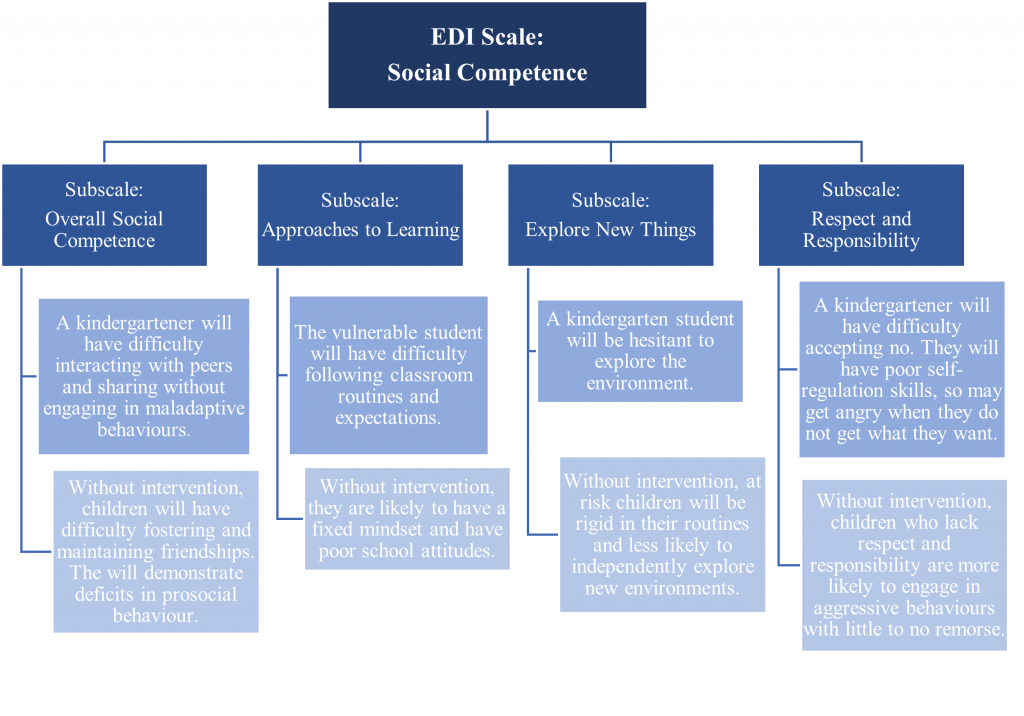

The social competence subscales, identified as Overall Social Competence, Readiness to Explore New Things, Approaches to Learning, and Respect and Responsibility, indicate a worsening trend in three of the four subscales. Readiness to Explore New Things is the only domain demonstrating an accelerating improving trend in the long-term (Early Development Instrument British Columbia, 2016-2019 Wave 7 provincial report).

Behaviours of Vulnerable Children and Intervention

Evidence-Based Interventions for Children Vulnerable to Social Competence Deficits

Children at risk for social competence are likely to have a difficult temperament. These children often receive less support and experience more hostile adult-child interactions, causing a bidirectional toxic relationship that worsens the child’s and the adult’s attitudes. By focusing on strategies for responsive and sensitive interactions with the child, the effect of the temperament can be weakened for more positive interactions. The parent-focused intervention aims to create a home environment that promotes resilience in these preschool children (Masten & Barnes, 2018). Using video modelling, the parent can learn about the concepts, see them in action, practice it, and discuss outcomes during the weekly check-in.

The intervention is based in the classroom addressing self-management skills. Self-management skills include problem-solving, self-regulation, dealing with conflict positively, winning and losing without maladaptive behaviours. Social Skills involve communicating emotions, asking for help, perspective-taking, interacting with peers, inhibiting negative behaviours (Mihic et al., 2016). Teachers would be trained to deliver the lesson to the children and contrive opportunities to practice these skills in the natural environment, outside of teaching (Mihic et al., 2016). Children need to recognize their emotions and the language to communicate them to trusted people in their community and their peers. In addition, they need to learn strategies for emotional regulation, which helps with conflict resolution and fosters stronger friendships as they grow older.

References

Bale, T.L. (2015). Epigenetic and transgenerational reprogramming of brain development. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16, 332-344. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3818

Berk, L. E., (2021). Revel Infants and Children: Prenatal Through Middle Childhood, 9e. Pearson.

Case-Smith, J. (2013). Systematic review of interventions to promote social-emotional development in young children with or at risk for disability. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67, 395–404. http://dx.doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2013.004713

Human Early Learning Partnership. EDI BC. Early Development Instrument British Columbia, 2016-2019 Wave 7 provincial report. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, Faculty of Medicine, School of Population and Public health; 2019 Nov. http://earlylearning.ubc.ca/media/edibc_wave7_2019_provincialreport.pdf

Human Early Learning Partnership. Early Development Instrument [EDI] report. Wave 7 Community Profile, 2019. Nechako Lakes School District (SD91). Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, Faculty of Medicine, School of Population and Public Health; February 2020. Available from: http://earlylearning.ubc.ca/media/edi_w7_ communityprofiles/edi_w7_communityprofile_sd_91.pdf

Human Early Learning Partnership. EDI (Early Years Development Instrument) W7 EDI Subscales Community Profile, 2020. Nechako Lakes (SD91). Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, School of Population and Public Health; January 2021. Available from: http://earlylearning.ubc.ca/media/edi_w7_communityprofiles/edi_w7_subscale_communityprofile_sd_91.pdf

Human Early Learning Partnership Early Development Instrument Data Library. Census and National Household Survey, 2016. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia; June 2018. Available from: http://earlylearning.ubc.ca/media/2016_census_for_uploading_to_datalibrary_13june2018.xlsx

Human Early Learning Partnership Early Development Instrument Help Data Library EDI Waves 2-7. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, February 2020. Available from: http://earlylearning.ubc.ca/media/vulnerablity_waves_2_through_7_2019_forweb.xlsx

Jones, D.E., Greenberg, M., & Crowley, M. (2015). Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. Journal of American Public Health, 105(11). pp. 2283-2290. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302630

Masten A.S. & Barnes, A.J. (2018). Resilience in children: Developmental perspectives. Children, 5(7), 98, pp. 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5070098

Mihic, J., Novak, M., Basic, J., & Nix, R. L. (2016). Promoting social and emotional competencies among young children in Croatia with preschool PATHS. International Journal of Emotional Education, 8(2), 45–59.

Parents: What is the EDI? (n.d.). Early Developmental Instrument. https://edi.offordcentre.com/parents/what-is-the-edi/

Thomson, R., & Carlson, J. (2017). A Pilot Study of a Self-Administered Parent Training Intervention for Building Preschoolers’ Social-Emotional Competence. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(3), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0798-6

December 13, 2021 at 5:19 pm

Great writing! You made it super clear to understand with the graphs and tables that were included. I think it would be a great idea to implement self-management skills in the school environment. Teachers can give homework assignments to practice these skills outside of the education setting and can apply them to the real world.

December 16, 2021 at 11:23 pm

Hi Leilani,

Wow, very well organized writing and great use of graphs. Developing social interaction skills when you are young really helps you later on in life, it seems like a great intervention for young socially vulnerable kids. Targeting social skills involving communicating emotions is an interesting idea, I think it would be especially important for certain demographics of young boys who are socially vulnerable and on top of that faced with large gender-typed forces discouraging particular emotional expressions, maybe a more specific intervention could be built for that particular issue. Great write-up, really well done!