by Rose Nah

The Physical health and well-being of the Early Childhood Instrument (EDI) includes physical readiness, physical independence, and gross and fine motor skills. Examples of physical health and well-being include holding a pencil, how much energy levels for school activities, running outside, or independence in looking after one’s own needs, and daily living skills. The questionnaires for physical well being asks about if the child is late to the school, if they independently goes to the washroom, what their ability to manipulate objects, climb stairs, proficiency at holding a pen, crayons, or a brush.

Resilience factors such as family problems, health problems, school problems, workplace problems, or financial problems could all affect a child’s development. Developmental systems approach’s (DST) essential idea is that both biological and behavioral traits come together and make a single complex system. DNA, cells that make up our body, hormones, neurotransmitters, organ systems, societal factors, and environmental features and own behavioral history.

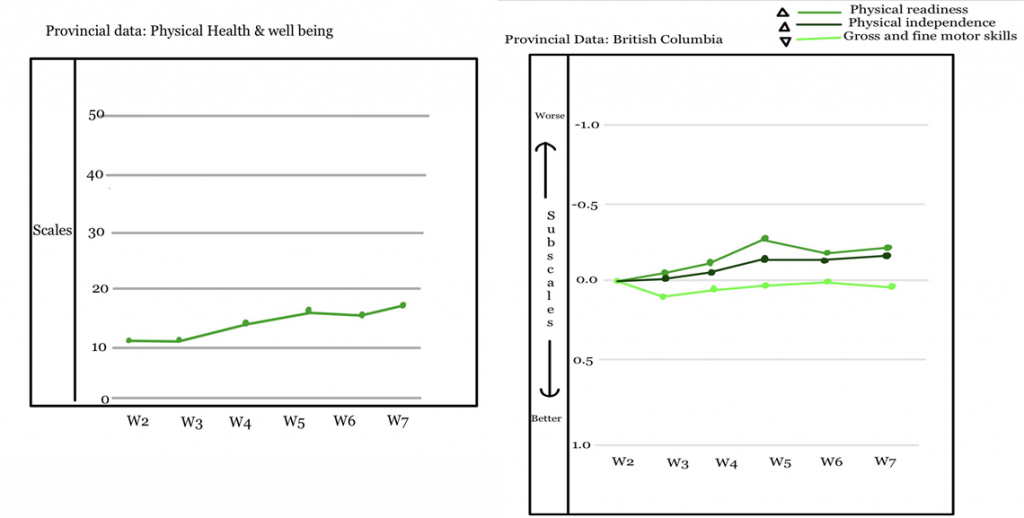

- British Columbia

- Physical well being vulnerability rate for wave 7 (15.4%) was significantly higher than wave 2 (12.0%)

- Both physical readiness and physical independence sub scales are in overall worsening trend

- Gross and fine motor in sub scale shows a stable trend overtime

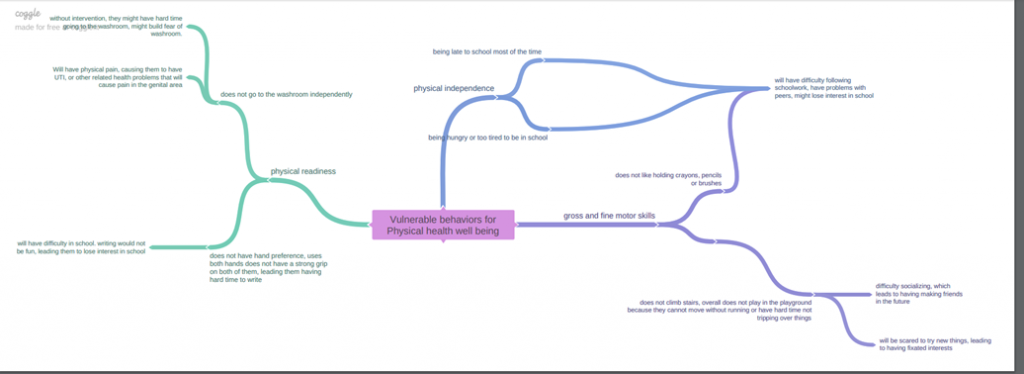

Examples of vulnerable behaviors for physical health well being

Interventions

- Toileting Intervention

- Priming and modeling: watching a video before doing the program increases the speed that the child learns the skills.

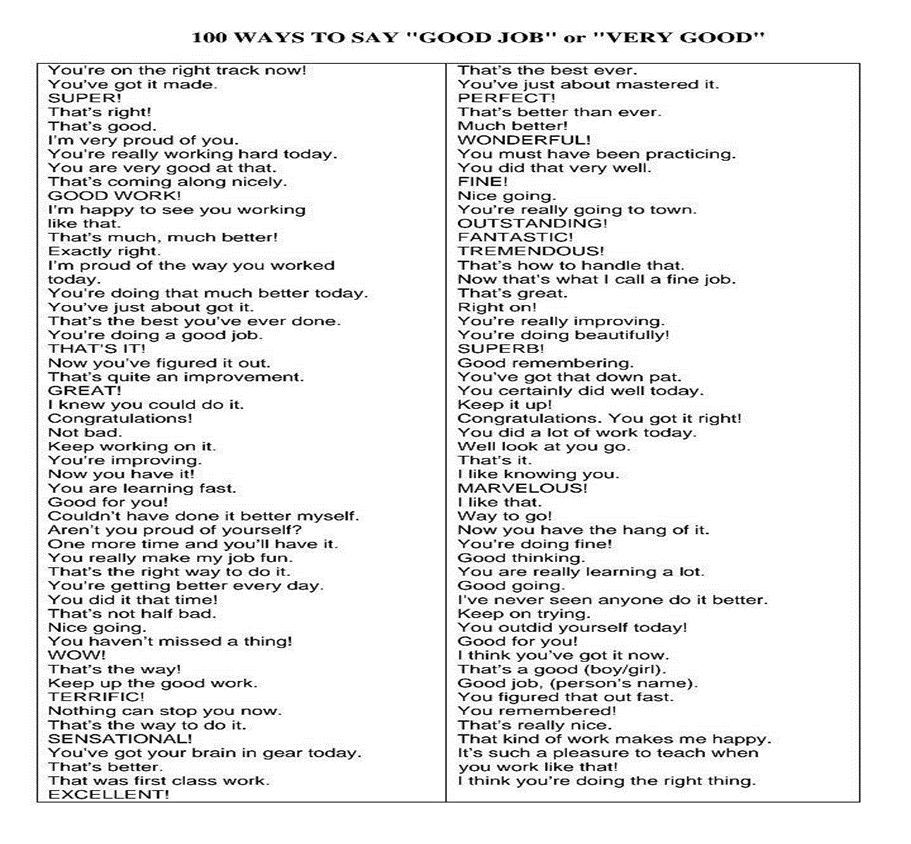

- Positive reinforcement : Social praises (e.g., Good job!, Nice work, Fantastic) is a reward for the child and reinforcements increase the desired behavior. Desired food could be a positive reinforcer as well. It is important to give positive reinforcements right away after the desired behavior happens.

- Schedule sitting: Before starting the program, first observe the behavior of the child in the washroom. Next, make a schedule (e.g., every 10 minutes or 60 minutes) and increase as it goes on. Then, place the child on or near the toilet. After they show desired behavior- which is going to the toilet independently- give reward and allow them to leave the washroom.

- Hydrations: This involves increasing the fluids that the child prefers. As they drink more, there are more chances that the child would go to the toilet.

When children have difficulty going to the washroom independently, it can heavily impact children’s lives when in school. It will also impact their physical health, such as pain in genital area and getting UTI. Using these methods will increase the frequency of children going to the washroom independently and decreasing undesired behavior.

- Physical independence

- Visual schedule: Having personalized schedules, and using the baseline data and seeing what they are capable of doing, we can make a visual schedule for the day to increase the productivity of the children. Time of waking up to time to go to bed will make them have increased sleep and have more energy for school. Having expectations throughout the day would make the children know what it expected in a day.

- Timers

- Sleep schedules: If the child is having difficulty sleeping, having a sleep schedule helps them have a better sleep in the long run. Sleep schedule is not letting them have naps throughout the day, but having sleep only at scheduled times. This will increase the quality of sleep as well.

- Motor imitation/ object imitation

- Using different materials like playdoh, fake sand, and games, prompt them to follow what you are doing

- For pencil holding and practicing having a grip, use different tools to increase probability to use them correctly

Don’t forget while using these interventions, using positive reinforcement is very important. Social praise increases the desired behavior. It is also important to note that positive reinforcer should come right after they performed desired behavior.

References

Bale, T. L. (2015). Epigenetic and transgenerational reprogramming of brain development. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(6), 332‐344. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3818

Cherry, K. (2020, March 16). How Genes Influence Child Development. Verywell Mind. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://www.verywellmind.com/genes-and-development-2795114

Conradt, E. (2017). Using principles of behavioral epigenetics to advance research on early‐life stress. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 107-112. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12219

Heim, C. M., Entringer, S., & Buss, C. (2019). Translating basic research knowledge on the biological embedding of early-life stress into novel approaches for the developmental programming of lifelong health. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 105, 123-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.12.011

Moore D. S. (2016). The Developmental Systems Approach and the Analysis of Behavior. The Behavior analyst, 39(2), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40614-016-0068-3

Berk, Laura E. (2021). Infants and Children: Prenatal through Middle Childhood (9th ed.). Pearson

Human Early Learning Partnership. EDI (Early Years Development Instrument) report. Wave 6 Community Profile, 2016. Burnaby (SD41). Vancouver BC: University of British Columbia, School of Population and Public Health; October 2016.

Human Early Learning Partnership. EDI BC. Early Development Instrument British Columbia 2016-2019 Wave 7 provincial report. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, Faculty of Medicine, School of Population and Public Health; 2019 Nov. Available from http://earlylearning.ubc.ca/media/edibc_wave7_2019_provincialreport.pdf

Human Early Learning Partnership. EDI (Early Years Development Instrument). W7 EDI Subscales Community Profile, 2020. Burnaby (SD41). Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia, School of Population and Public Health; January 2021.

April 26, 2022 at 3:51 pm

Hi Rose, nice post, I especially liked your suggested program as it is very detailed and covers several aspects of physical wellbeing. And it’s nice that you use a lot of examples to illustrate what physical wellbeing in children looks like. Something I really liked about your post is that you used a lot of graphs and pictures, but one of them (the one with the concept map) is a bit difficult to read. And one small thing, is it possible you meant risk factors, not resilience factors when talking about family problems, health problems, school problems, etc.?

April 27, 2022 at 11:16 am

Hi Rose, I appreciate the amount of detail you put into your interventions section, you really broke down each component effectively. Also great use of images to make the blog post come alive. This was definitely not an issue I would have viewed as very significant, but understanding the various physical and mental strains it can put on children definitely got me thinking. Great post!