Built in 1851 for the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, London, the Crystal Palace was one of the most innovative buildings of the 19thcentury. Many historians have credited its construction to be a precursor to modern architecture (Charney, 1998).

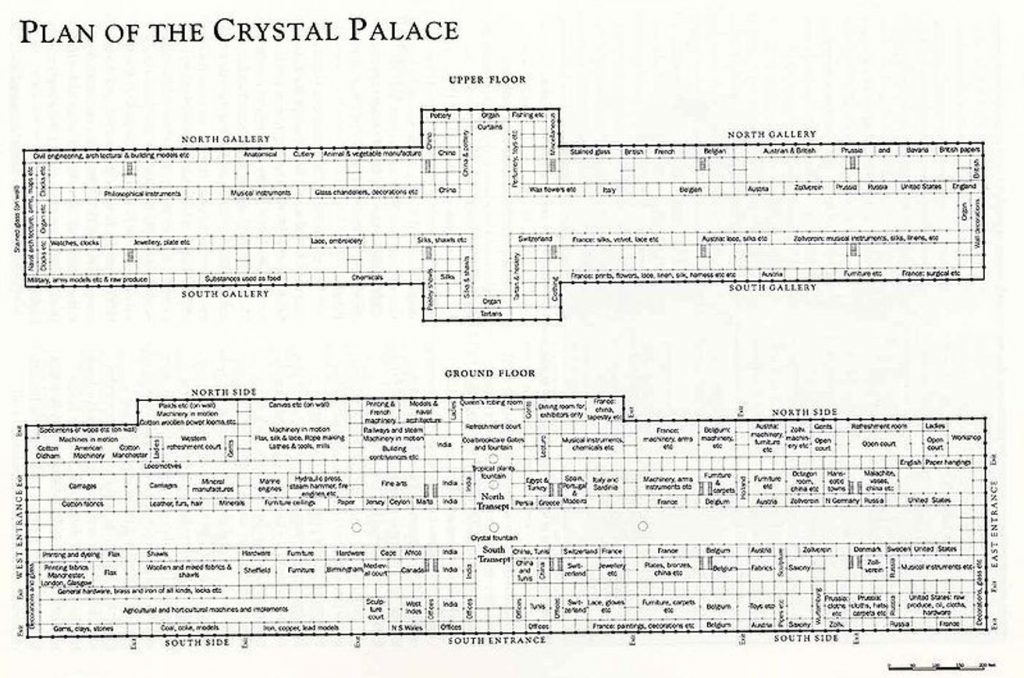

The idea for the exhibition was proposed by Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, in 1849. The Royal Commission overseeing the project called for a building that needed to cover 800,000 sq. ft. on a £100,000 budget, making it the largest building ever constructed at the time and cheaper than any other building built before it (Addis, 2006).

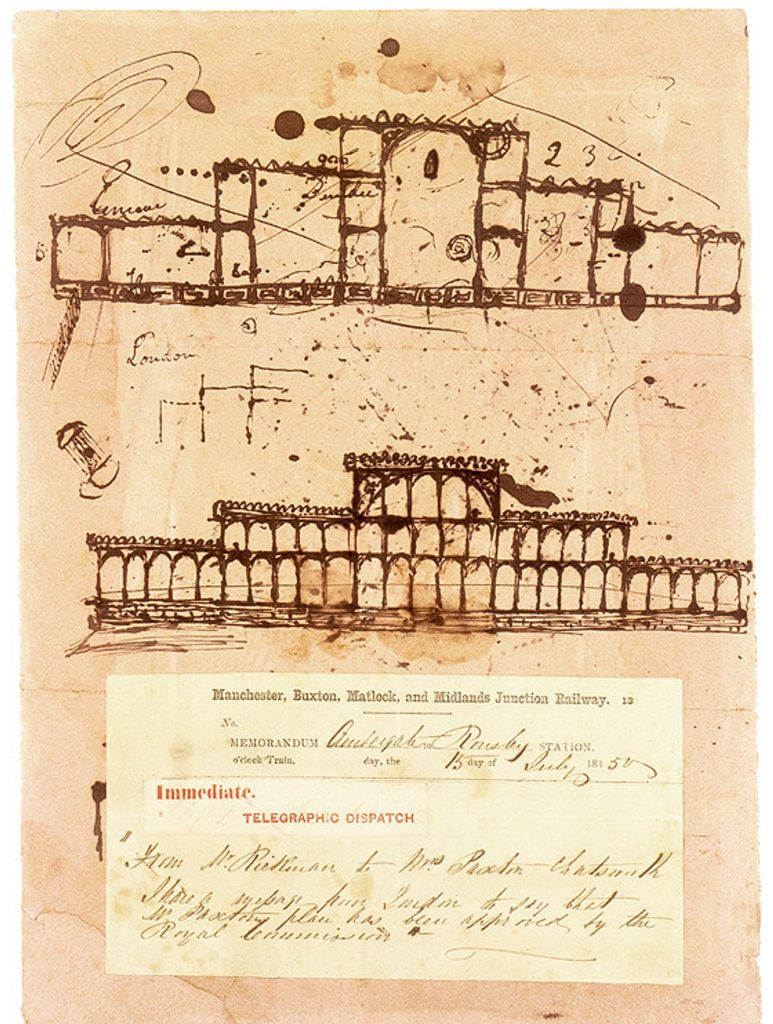

The building had to be ready by the time the exhibition was scheduled to open on May 1st, 1851, so a design competition was announced on March 13, 1850, with a deadline of April 8th (Addis, 2006). Within 3 weeks, 245 entries were received, but were all rejected. As a last-ditch effort, the committee tried to come up with their own design, but it was highly criticized and ridiculed by the public (Lancaster, 1998). It was only after this that Paxton showed interest in the project (Merin, 2013).

Joseph Paxton was a horticulturist best known for being the gardener for the Duke of Devonshire. The design for the Crystal Palace was modeled after a house he built for the Duke to house an Amazonian lily he brought back to England (Miller, 2017).

Paxton’s Crystal Palace involved several breakthroughs in that the design was the first to make use of the cast plate glass method invented in 1848, which made it possible to produce large sheets of glass at a lower cost. The largest sheet of glass that could be made at the time was 10 inches wide by 49 inches long, so Paxton designed his building around those specifications (Miller, 2017).

The resulting design allowed London to build the largest building in the world in only eight months, reaching over 560 meters in length, to which 14,000 exhibitors gathered in a single space (Another Studio, 2014).

After the Exhibition, the structure was dismantled and relocated to Sydenham, South London, where Paxton made some adjustments to accommodate the larger area. It eventually re-opened in 1854 to become a ‘Palace of the People’ and hosted numerous shows and exhibitions over the years (The Strawberry Post, 2021).

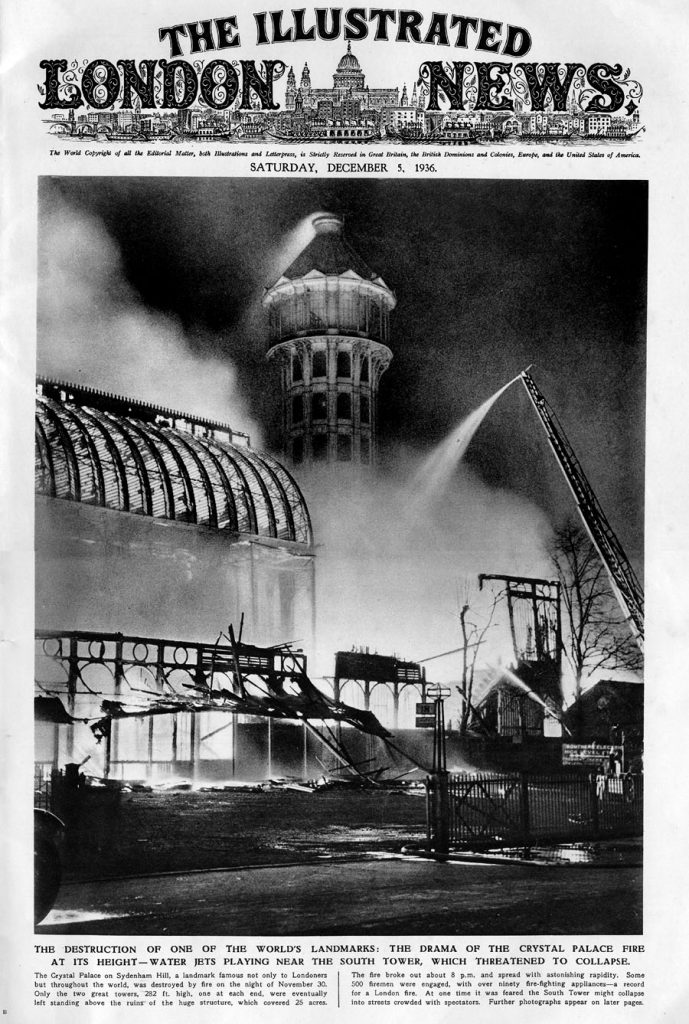

Unfortunately, on November 30, 1936, the Crystal Palace was destroyed by a massive fire. As much as 100,000 people gathered that night to witness the destruction. Among the onlookers was Winston Churchill, who reportedly watched with tears in his eyes and said, “This is the end of an age” (as cited in Clark, 2016), while Sir Henry Buckland, the general manager for the Crystal Palace, told reporters the structure would continue to “live in the memories not only of Englishmen, but the whole world” (Exploring London, 2021).

References

Addis, Bill. (2006). The Crystal Palace and its Place in Structural History. International Journal of Space Structures. 21. 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1260/026635106777641199

Another Studio. (2014, May 29). The Crystal Palace, A Lost Building. https://www.another-studio.com/blogs/news/the-crystal-palace-lost-buildings

Charney, W. M. (1998). Materializing through the Skylight: How the Crystal Palace Acquired its Architectural Significance. Oz, 20, 28-53. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2378-5853.1323

Clark, N. (2016 November 28). What happened the night the Crystal Palace burnt down? Express. https://www.express.co.uk/news/history/737044/Crystal-Palace-fire-1936

Exploring London. (2021, November 1). A Moment in London’s History – Crystal Palace burns… Exploring London. https://exploring-london.com/tag/crystal-palace/

Kihlstedt, F. T. (1984). The Crystal Palace. Scientific American, 251(4), 132–143. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24969462

Lancaster, D. (1988, October). History of the Crystal Palace (Part 1). The Crystal Palace Foundation. The Valuer. http://www.crystalpalacefoundation.org.uk/history/history-of-the-crystal-palace-part-1

Merin, G. (2013, July 5). AD Classics: The Crystal Palace / Joseph Paxton. ArchDaily. https://www.archdaily.com/397949/ad-classic-the-crystal-palace-joseph-paxton

Miller, M. (2017, May 17). How A Glorified Greenhouse Became Modernism’s Most Influential Building. Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/90125522/how-a-glorified-greenhouse-became-modernisms-most-influential-building

Sreekanth, P. S. (2011, June 10). Joseph Paxton – Crystal Palace – Detailed Analysis. The Archi Blog. https://thearchiblog.wordpress.com/2011/06/10/joseph-paxton-crystal-palace-detailed-analysis/

The Strawberry Post. (2021, November 30). The Fire That Destroyed the Victorian Crystal Palace, 85 Years Ago Today! https://thestrawberrypost.wordpress.com/2021/11/30/the-fire-that-destroyed-the-victorian-crystal-palace-85-years-ago-today/#comments

Tom R. (2019, November 28). Crystal Palace was “birth of modern architecture” says Norman Foster. Dezeen. https://www.dezeen.com/2019/11/28/norman-foster-crystal-palace-modern-architecture/