Discovery

In 1900 British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans (1851-1941) began excavating a dig site at Knossos, located on the island of Crete. He discovered what he believed was the ruins of King Minos’ palace, which according to legend, contained the labyrinth that housed the Minotaur.

In the ruins, he uncovered thousands of clay tablets written in a script that bore no resemblance to hieroglyphs, cuneiform or the later Greek alphabet (Robinson, 1995). This script was named Linear B.

Linear B would eventually go on to become the oldest form of written Greek that we know of today, but this knowledge eluded scholars from around the world for over 50 years until it was deciphered in 1952 (Cook, 2014).

Despite his efforts, not even Evans was able decipher Linear B during his lifetime, but he did make several observations in his research.

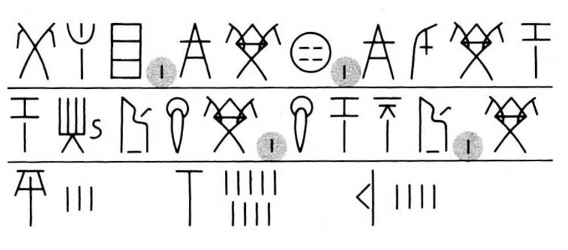

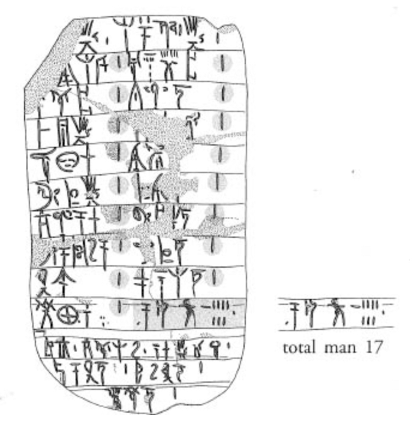

He identified the short upright lines that recurred between characters to be word dividers:

He identified a numerical system of counting:

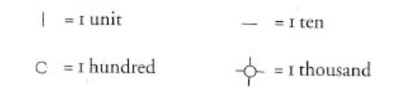

He also figured out that many of tablets were inventories, with a total at the bottom, often depicted in the form of a pictogram:

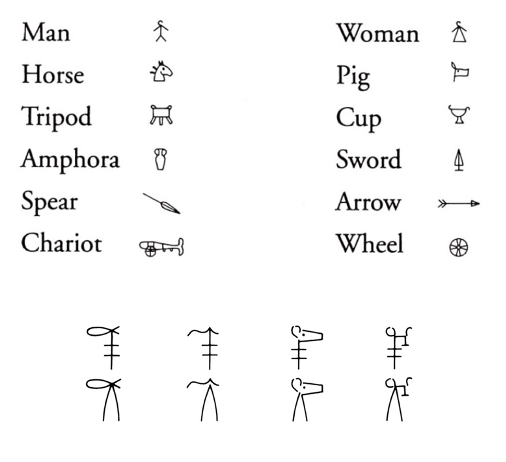

Other pictograms were more obvious in representing words, many of which had two forms, presumably to differentiate between male and female:

Evans and other linguists also deduced the script to be syllabic, with each character representing a syllable, as opposed to a sound or word (Craddock, 2014).

Cracking the Code

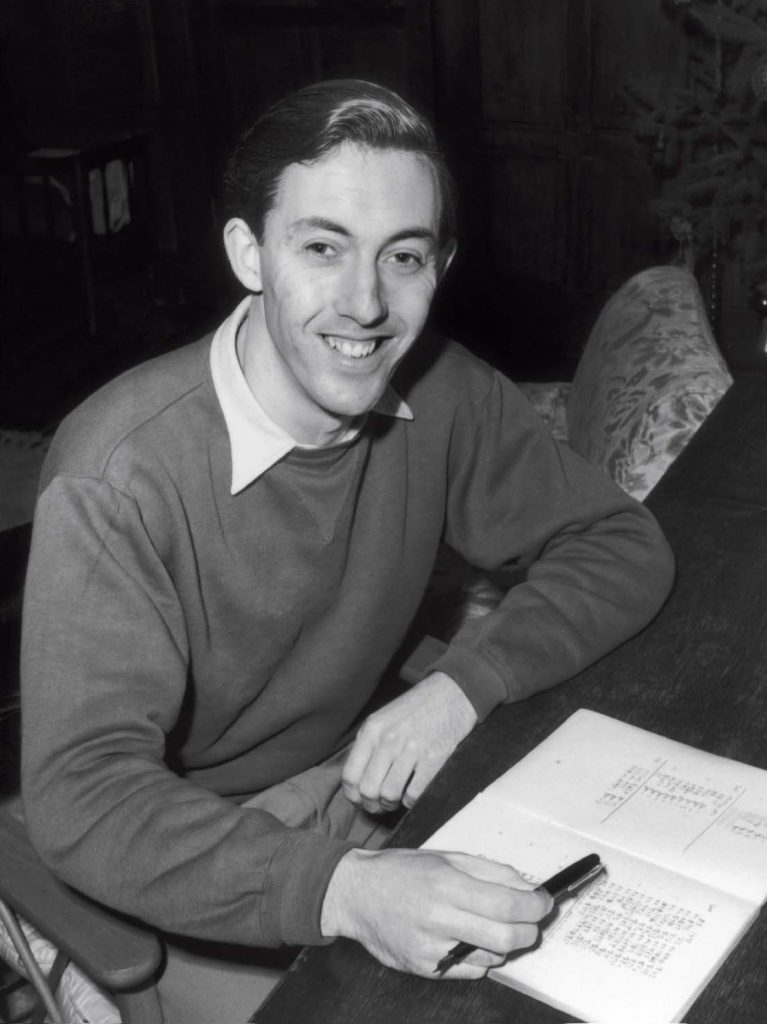

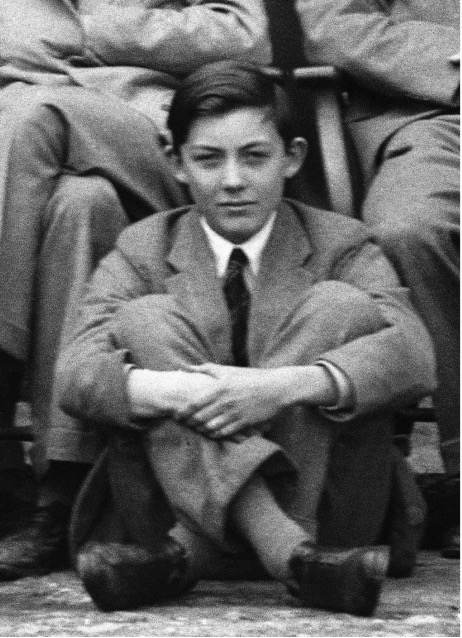

In 1936, while attending an exhibition in London where Sir Arthur Evans was speaking, a 14-year-old Michael Ventris became inspired by Evans lectures to decipher Linear B himself.

(Photo R. & H. Chapman, courtesy Tony Meredith) (Robinson, 2002, p. 31)

Ventris was born on July 12, 1922. He grew up to be an architect by profession and served as a navigator in the Royal Air Force during World War II (Craddock, 2014).

In 1952, he successfully deciphered Linear B.

The eventual decipherment of Linear B, in 1952, by a British architect, Michael Ventris, ranks second only to that of Jean-François Champollion’s decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs in 1823. (Robinson, 1995, p.109)

Despite this accomplishment, it’s worth noting that Ventris’ success may not have been possible without the help of a few others.

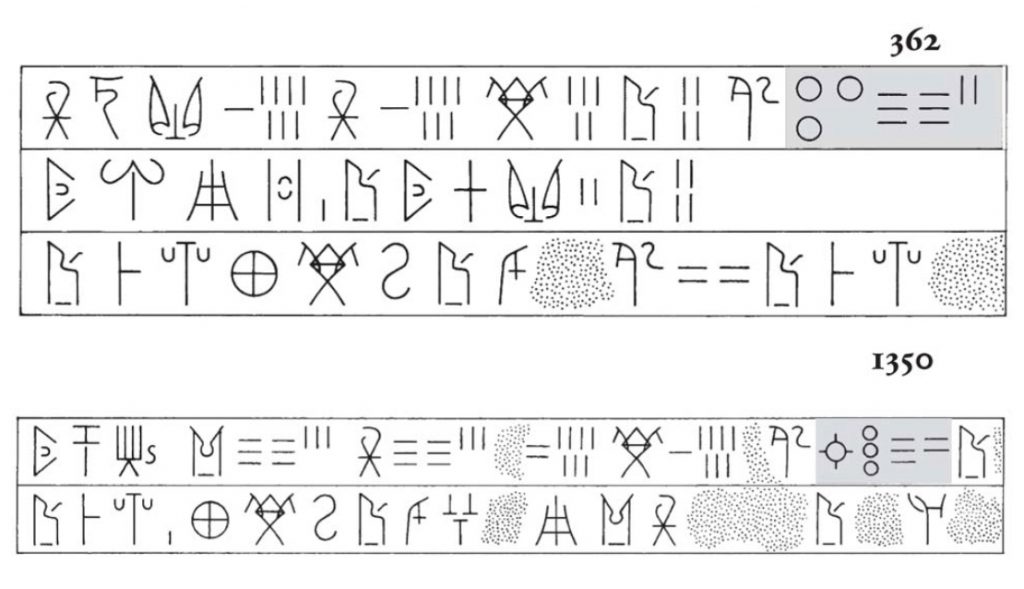

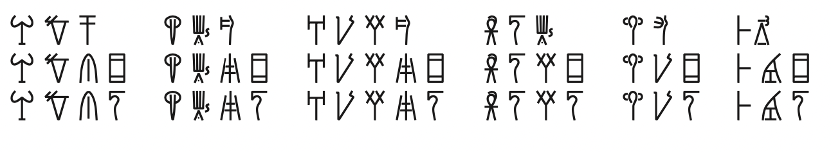

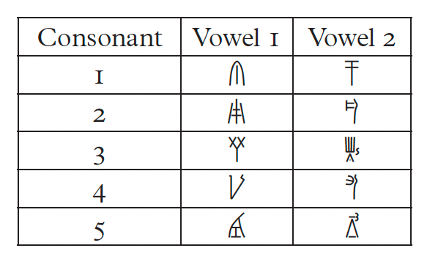

Alice Elizabeth Kober was an American linguist and scholar, who laid out much of the groundwork that would help Ventris in deciphering Linear B (Craddock, 2014). Kober was able to identify examples of inflection in the script, in which the same word would appear with different endings in different contexts:

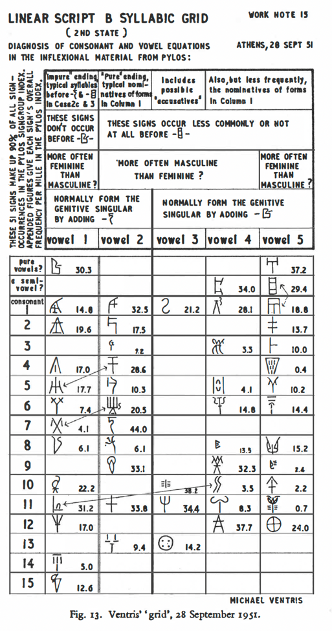

From this information, Kober constructed a grid to identify the relationships between these signs:

Using Kober’s findings, which Ventris aptly named ‘Kober’s triplets,’ he was able to construct a grid of his own to identify additional consonants and vowels. This eventually led to his discovery that the characters on the Knossos tablets were place names (Galanakis, 2017).

Despite his findings, however, he remained skeptical of Linear B being anything other than Greek. It wasn’t until 1951, with the help of John Chadwick, an expert in early Greek, were they were able to fully decipher the script and identify the language as an archaic dialect of ancient Greek. (Waskey, 2016).

Evidently, Linear B was derived from another script classified as Linear A, which still remains undeciphered to this day (Sacks, 2015).

References

Alice Kober. (2014). In J. Craddock (Ed.), Encyclopedia of world biography (2nd ed.). Gale. Credo Reference: https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galeworld/alice_kober/0?institutionId=6884

Chadwick, J. (1970). The Decipherment of Linear B. The Syndics of the Cambridge University Press

Dashwood, R. (2002). A Very English Genius – Michael Ventris – BBC Documentary 2002. YouTube. www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Fn9wVPAYAo.

Michael Ventris. (2014). In J. Craddock (Ed.), Encyclopedia of world biography (2nd ed.). Gale. Credo Reference: https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galeworld/michael_ventris/0?institutionId=6884

Cook, J. W. (2014). Linear B. In J. W. Cook, Encyclopedia of ancient literature (2nd ed.). Facts On File. Credo Reference: https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/fofal/linear_b/0?institutionId=6884

Fagan, J. (1970). The Great Archaeologists. Thames & Hudson.

Gallafent, B. M. (2014). Alice Kober: Unsung Heroine Who Helped Decode Linear B. BBC News. www.bbc.com/news/magazine-22782620.

Galanakis, Y. (2017). Codebreakers and Groundbreakers. The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge

Palaima T.G. (1993). Michael Ventris’s Blueprint: Letters reveal how a British architect and two American scholars worked to decipher a Bronze Age script and read the earliest writings in western civilization. Discovery: Research and Scholarship at the University of Texas at Austin. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/63628/palaima_1993.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Robinson, A. (1995). The Story of Writing. Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

Robinson, A. (2002). The Man Who Deciphered Linear B: The Story of Michael Ventris. Thames & Hudson Ltd, London

Sacks, D. (2015). Linear B. In D. Sacks, Facts on File library of world history: Encyclopedia of the ancient Greek world (3rd ed.). Facts On File. Credo Reference: https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/fofancient/linear_b/0?institutionId=6884

Waskey, A. J. (2016). Linear a and B. In Facts on File (Ed.), World history: a comprehensive reference set. Facts On File. Credo Reference: https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/fofworld/linear_a_and_b/0?institutionId=6884