Overview

In the early 20th century the Western art world was completely redefined by the wave of avant-garde that flooded across Europe and North America. This period was a time of immense change; advances in technology and industry, world war, politics, and plague affected every aspect of life. Artists reacted to this change by rejecting logic, reality, and tradition; they became pioneers themselves, seeking to create a form of art that reflected their new world. The Modernists, as they came to be known, were made up of various groups, each with their own distinct aesthetics and philosophies; some became political, some were philosophical, or spiritual, but the one thing they had in common was that they were all experimental. Each group played off of the others; adopting or rejecting new ideas and aesthetics, building upon or paring down concepts.

Modernists believed that everything in life could be defined and categorized and that by specifying, abstract concepts became easier to understand. They wanted to convince, convert, shock, inspire, and sometimes, even offend. One tool in particular became very popular amongst this generation of creatives, and that was the artist’s manifesto.

Manifesting A Definition

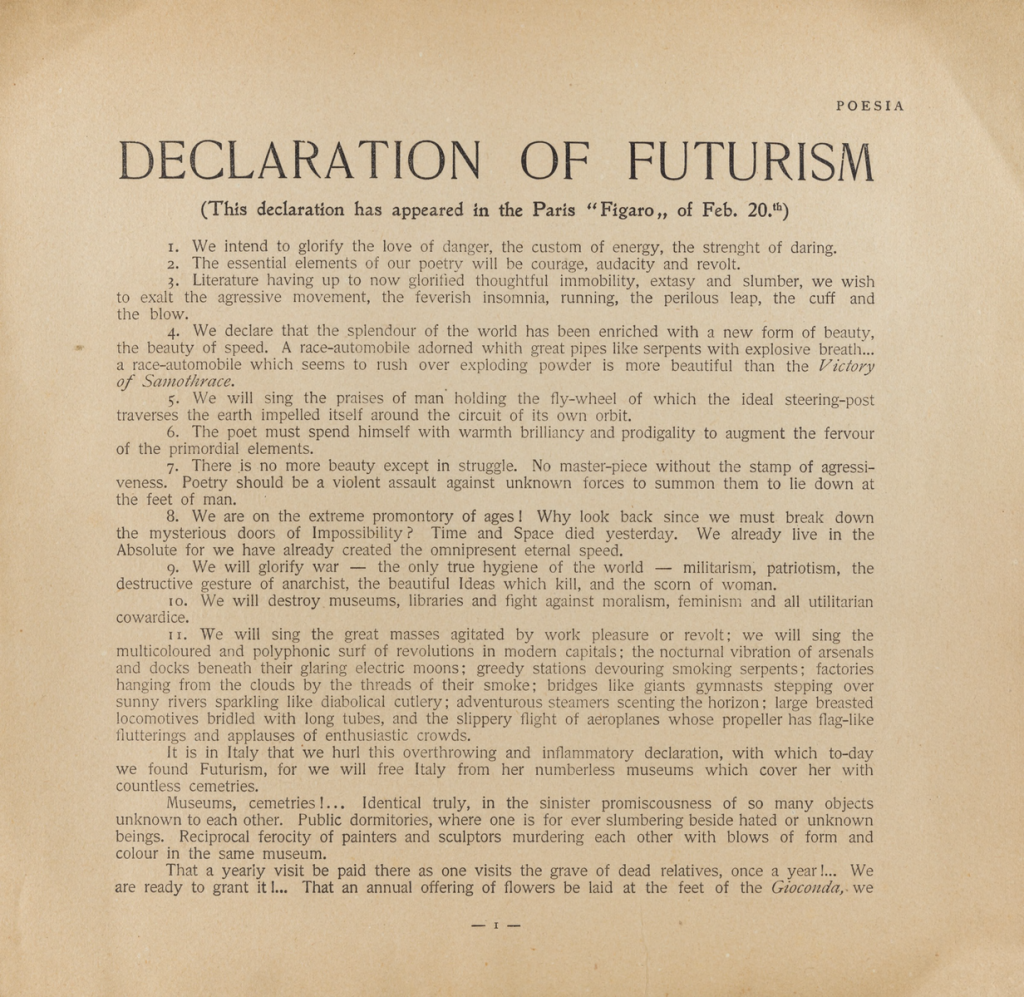

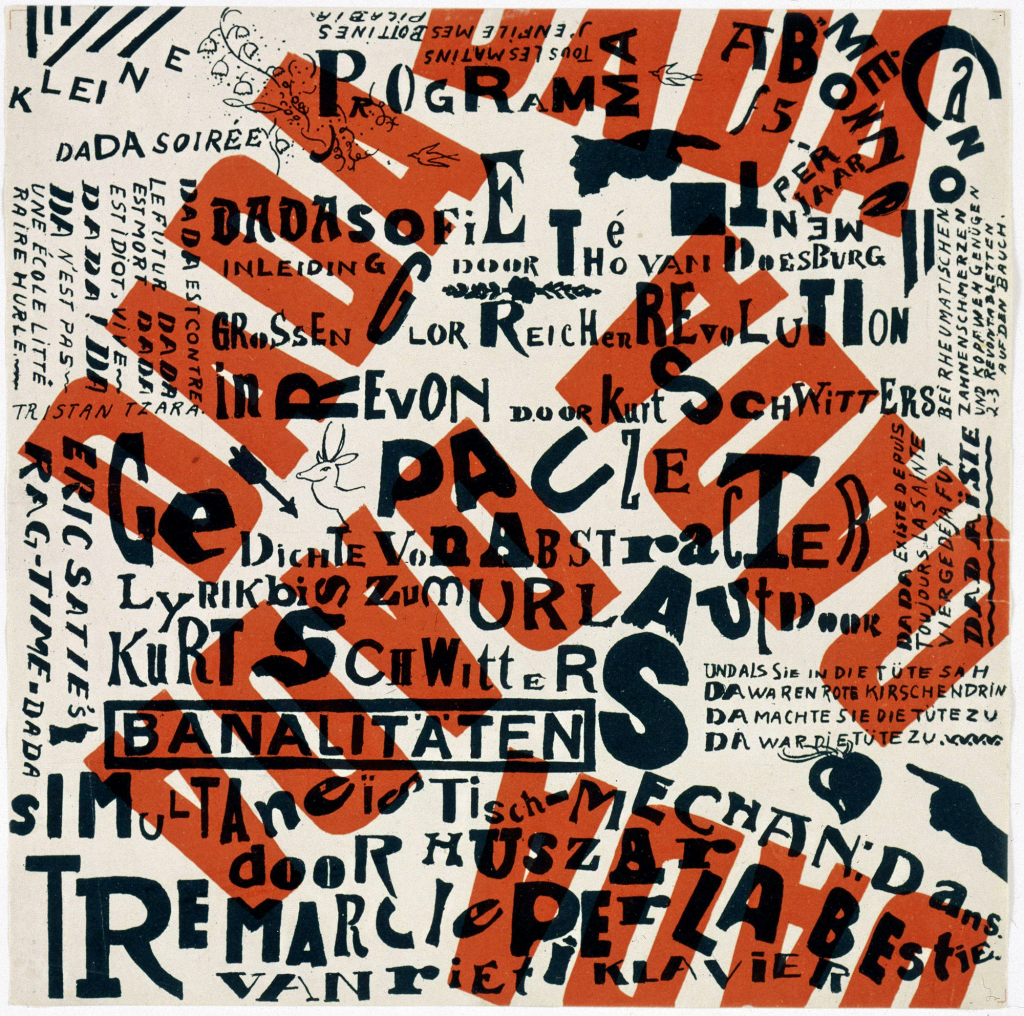

A number of groups and individuals associated with the Modernist movement took to creating these manifestos, which were public declarations used to aid their art movements by defining their intentions, motives, or views. Manifestos were intended to be works of art themselve; usually they were published in magazines or newspapers relying heavily on graphic design, although some were created with the intention to be used in performance art.

Manifestos had a number of uses; they were often used to define and criticize a pattern in contemporary art, and then define a set of aesthetic values to counter this pattern. Sometimes they would also address wider issues, such as the political system, a need for revolution, or freedom of expression. They usually consisted of a number of statements, which notably, did not always follow logically.

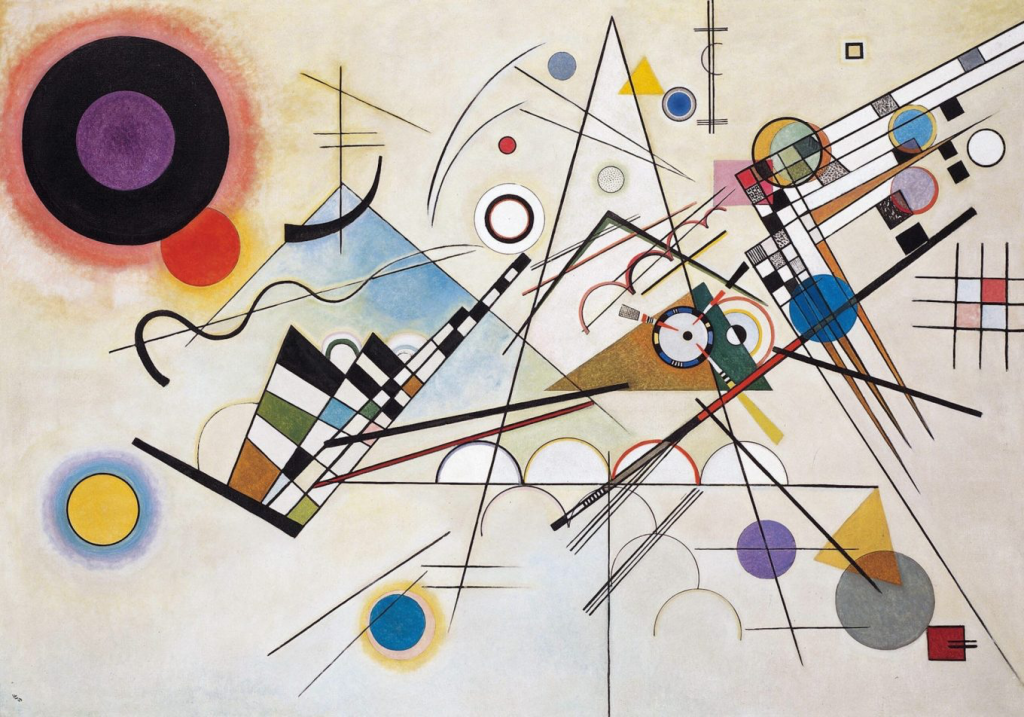

A few of the most influential movements of the 20th century that created manifestos were the Futurists, Cubists, Suprematists, DADAists, the De Stijl, the Bauhaus (specifically Wassily Kandinsky), as well as the Constructivists, Purists and Surrealists.

“Every artist, as child of his age, is impelled to express the spirit of his age (this is the element of style) — dictated by the period and particular country to which the artist belongs (it is doubtful how long the latter distinction will continue to exist).” – excerpt from “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”, which was Kandinsky’s personal manifesto

The Next Minute

The period between 1900 and into the 1930s came to be known as the “minute of manifestos”; although art manifestos continued to be created following WWII, and are still occasionally used to help define the intentions of specific artists today, they have mostly fallen out of practice with the rise of Post Modernism and the promotion of individualism. Contemporary artists now tend to embrace the idea of chaos and uncertainty; they believe that to truly categorize a concept is impossible, and absolute knowledge inaccessible, very unlike their predecessors, who sought to explain everything they did.