Introduction

As a woman author, my interests often lean towards investigating the lives of past female writers. I believe it is very important to know what came before you in order to truly appreciate what you are a part of today. The history of women authors, however, is not a very popular topic. The underrepresentation of women writers has been an issue since women’s work first appeared in print. Limitations and boundaries were drawn in regards to what women could read or write. In 1984, “only 31 percent of authors at that time were women” (Gerson 197). In 2013, “this number developed to be 45 percent” (197). Thus, clearly, the limitations of the past have diminished significantly today. But, how did we get from restriction to freedom?

The way women’s place in the writing community has evolved is an interesting process to observe. By bringing to light the struggle and success stories of women writers, especially in the Capilano community, we can understand and appreciate the dynamic that exists today between women and the publishing world. By narrowing down the history of female authors and focusing on our local magazines such as The Capilano Review, we are able to observe the gender hierarchies still present today.

To begin my project, I contemplated the perceptions people have had of female authors in the past by reading the history of Canadian women writers. As I continued with my investigation, I applied the past to help me understand the present. I analyzed the effects these perceptions have had on The Capilano Review female writers by interviewing past editors and analyzing The Capilano Review anniversary issues ranging from 1979 until 2012. This research allowed me to observe how much the Capilano community has contributed to the underrepresentation of women authors.

History

For my research, I found various scholarly sources that speak about how things were in Canada before for female writers. In Literary Culture and Female Authorship in Canada 1760-2000, Hammill writes that “arriving in Quebec in 1763, she [Frances Brooke] found virtually no literary culture in place” (Hammill 2). Afterwards, she proceeds to speak about how “there was little in the local society to encourage Canadian fiction in English” (2). Women in Canada were also limited as to what they could write and read.

In “Discovering Early Canadian Women Writers,” Julie Roy writes about the restrictions women faced when attempting to publish in the 18th and 19th centuries. In order to attract female readership, these authors published stories featuring extraordinary women, biographies, marriage, and etiquette. All of these published works had a moral dimension, however. Roy explains that “certain publishers went so far as to provide explicit assurances about the morality of the texts presented and their suitability for women” (“Discovering Early Canadian Women Writers”). Back then, there was a criterion to what women could read or write and, today, this criterion is not as present.

Even though a criterion is not present, judgments still linger. I realized this as I explored a more recent example of how women authors are portrayed. I read “Why Can’t a Woman (Writer) Be More Like a Man,” an article from 2011. Here, Stephen King’s opinion on early women writers and their nature is featured. When Weiner asks about women writers, King says that it is “true that men’s books are, still, almost always, taken more seriously.” A good example of this phenomenon is Joanne Rowling’s experience with her editor. When she was about to publish her first Harry Potter book, her editor advised her to change her name to J.K. Rowling in order for people to believe she was a man. This happened in 1997; however, things have changed since then and are still changing today. Weiner’s conclusion in her article was that, with time, everyone will have a safe space in the writing community. This space, as I later realized in my research, emerges from The Capilano Review.

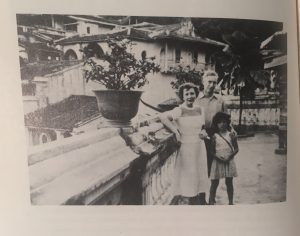

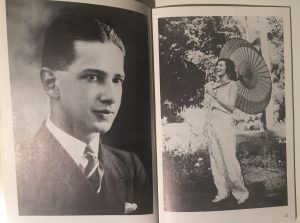

The past shone a light to how much progresses we have made, yet it also gave some context to frame my own experiences. An example that came to mind as I did research was my grandmother. She was an amazing writer and poet during the 1950s. As a child, I used to listen to her stories about the challenges she faced when she was an emerging author. She explained that my grandfather believed women belonged at home. One day, he went so far as to make my grandmother choose between either being a wife or being a writer. My grandmother believed in women’s rights, thus she decided to give up her life as a wife and be a writer instead. This inspiring memory made me realize how close people’s individual stories are to the issue of women authors and their underrepresentation.

When I interviewed Brook Houglum, one of the previous editors for The Capilano Review, this topic surfaced as well. She told me that her grandmother had experienced something similar. She was “an amazing knitter and had started her own company.” However, when she got married, all her personal projects halted and she had to dedicate her time to the family instead. As well, we spoke about how, today, people frown upon women staying at home. Together, we realized there is an imminent contrast between past and present perceptions. After a while, we concluded that the key is finding balance. Some women enjoy staying at home and some wish to work, but it is crucial for women around the world to be able to choose.

Findings & Local Examples

It is interesting to see the relationship between the research I found and The Capilano Review. To answer my research question, I chose four primary sources: The Capilano Review’s 1979, 1993, 2002 and 2012 anniversary issues. My goal was to explore whether there was an underrepresentation of women writers within these issues. As I read the past experiences of Canadian female writers, which ranged from the 1700s up to 2015, I thought I knew the answer to my research question. I believed that, if the number of women writers increased through history, the same would happen in The Capilano Review.

I was very confident when I began analyzing the anniversary issues. At first, I thought my assumptions were right since the 1979 anniversary issue was composed of 20% females and 80% males. Furthermore, the images that accompanied the writing in the 1979 issue portrayed women in “supporting” roles. Their clothing in these pictures suggested women often stayed at home while men went to work.

However, as I continued my research, what I discovered was unexpected. Just fourteen years later, the numbers had flipped completely. There was an overrepresentation of women in the subsequent issues rather than an underrepresentation. I was aghast as I recognized that, in the 1993 issue, the number of women writers had tripled. The contributors to this issue were 70% women and 30% men. My assumptions were wrong, I was expecting female gender inequality to be present in The Capilano Review issues, yet this inequality had vanished after 1993.

For the 2002 anniversary issue, the numbers evened out significantly. There were 55% women and 45% men, which showed me equality was becoming more evident. For the 2012 issue, a perfect balance had been reached: the number of male and female contributors had become even. Today, much more awareness is present around gender equality, and this was represented in my findings.

Thereafter, I asked myself “why?” This new discovery made me wonder what made The Capilano Review stand outside the norm. To satisfy my curiosity, I interviewed one of the former editors of the magazine, Brook Houglum. As I asked her what the most abrupt change was when she worked as an editor, she pointed out something unexpected. She said that what she noticed changing the most during her time as an editor was the “inclusion of many cultures and genders.” Thus, because of this, women were increasingly featured in The Capilano Review.

This showed me why The Capilano Review is an exception when it came to answering my research question. The magazine’s nature was always progressive and they stayed true to their image even when the world around them was different. Since 1979, the magazine was concerned with “what does ‘I’ mean” and on “private meaning” rather than gender (The Capilano Review 2). This same exploratory thinking is seen in the 2012 anniversary issue. Here, they “celebrate contemporary innovative writing and art” (The Capilano Review 5). This statement incorporates a diverse range of writers, including women. The fact that The Capilano Review had a divergent way of thinking since the beginning made them shine a light towards women authors when it was difficult to do so.

As we chatted all the more, Brook also pointed out that the “Vancouver writer’s community has always been experimental, particularly in the 1980s and the 1990s, which had a lot of really engaged, amazing and innovative women writers in it,” she said. Within these talented writers were Lisa Robertson, Catriona Strang, Christine Stewart and Nancy Shaw. Brook commented that “these women also built on the work of prior experimental women poets in Vancouver such as Daphne Marlatt and Maxine Gadd.” Daphne Marlatt’s writing is represented throughout the years, she was a part of the 1979, 1993 and 2012 issues. As well, an interview with Maxine Gadd is featured in the 40th anniversary issue. The contributions of these women writers to the poetic and experimental literary community in Vancouver was profound, and this was reflected in The Capilano Review and other magazines.

Conclusion

My lack of awareness was odd at first. I had not realized, but women authors have had to go through a lot to get to where we are today. This investigation shone a light in my mind to the struggles women writers have experienced in the past. My findings, even though they were unexpected, were uplifting. They prompted me to investigate even further and include this research in future projects. The history of women writers is fascinating and worth exploring all the more.

Regardless of there being many limits directed towards female authors, The Capilano Review stood true to their beliefs since the beginning and kept strong. Women contributors, such as Daphne Marlatt and Maxine Gadd, were an inspiration for me. Hope was sparked within me when I realized that there are exceptions to the rule and that, as long as there are some people thinking outside the box, there will always be a safe space for the unheard voices to break the limits and speak at last. I am thrilled to be a part of a community that has worked very hard to stand where they are today. As we work together, our voices will keep being heard. And, with time, we will inspire other generations of women writers to emerge and stand by our side.

References

Gerson, Carole. Canadian Women in Print 1750-1918. Wildfrind Laurier

Hammil, Faye. Literary culture and female authorship in Canada 1760 – 2000. Rodopi,

Houglum, Brook. Personal Interview. 27 Nov. 2017.

Houglum, Brook, et al. The Capilano Review. 3.17. 40th anniversary issue, 2012.

Roy, Julie. “Discovering Early Women Writers.” Periodicals: An Invaluable Resource on the History of Women. Unknown. http://www.canadiana.ca/women-magazines.

Sherrin, Robert, et al. The Capilano Review. Series 2, No. 10. 20th anniversary issue. 1993.

Thesen, Sharon, et al. The Capilano Review. 16/17. 2-3, 1979.

Thesen, Sharon, et al. The Capilano Review. Series 2, No. 37. 30th anniversary issue. 2002.

Weiner, Jennifer. “Why Can’t a Woman (Writer) Be More Like a Man?” The Huffington Post, TheHuffingtonPost.com, 12 Mar, 2009, www.huffingtonpost.com/jennifer-weiner.