Originating from Italy in the 1900s, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti founded Futurism, a movement which sought to destroy the past in art and society. During the life of the Futurists, they managed to spread their influence well past the scope of Italy into countries all around the world where Japanese writer Ōgai Mori is believed to be the first to bring Futurism into Japan. Since then, Futurism in Japan expanded to philosophy as well as art where several painters adopted aspects of the Futurist movement.

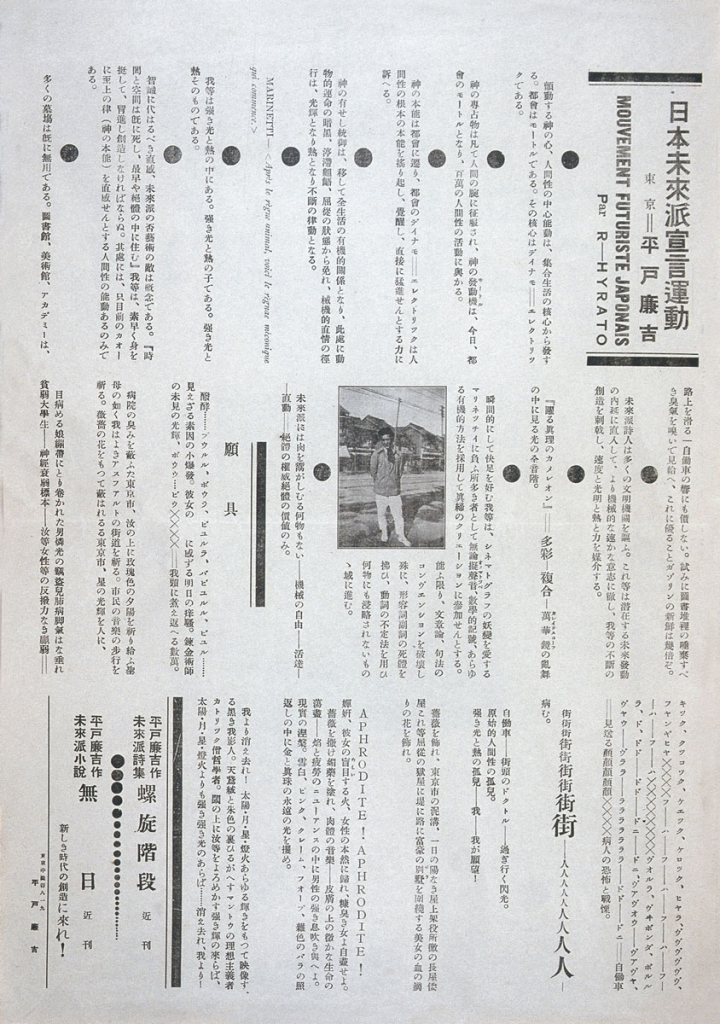

Westerners often perceive Japan as a futuristic country with all of it’s technological advancements and depictions in media. However, the country is very traditional in its history and beliefs even in the modern era. Thus, Ōgai’s translation and writing on Futurism was neglected for years until the topic came up again after Futurist exhibitions brought more international attention to the movement in 1912. There are several articles which covered the works in these exhibitions, as well as original Japanese Futurist Manifestos.

As Japanese art was transitioning from Impression to Post-Impressionism young painters became interested in the Futurist and Western painting style as a whole. Some of these artists made contact with Marinetti himself through writing or visiting Italy and wrote several articles which feature Futurist works and information sent by Marinetti.

One of the major painters of the time was Seiji Tōgō, famous today for his female portraits that feature surreal elements. He got his start through Italian Futurism and Cubism as did many other avant-garde painters at the time. Many of the important elements of Futurist paintings like movement, energy, and dynamism are present in his portraits. This is an implementation of those elements that are unseen in the Italian works and Tōgō was praised by Marinetti for those works. Tōgō incredibly greeted the audience at a Futurist event but later came to distance himself from the movement.

Well respected printmaker Yoshirō Nagase also attempted to implement the Futurist ideas in some of his earlier works. He also made a sketch which imitated some of the Futurist painting elements for his essay “Fyūchirisuto no gutaiteki kaishaku” (Concrete Interpretation of the Futurists) published in the September 1913 issue of a Tokyo magazine. He sought to create a portrait of his friend utilizing the Futurist style but created a mix of Cubism, Neo-Primitivism, and Futurism and many critics do not believe that it is befitting of the Futurist style.

Sources:

Berghaus Günter, and Pierantonio Zanotti. “38 Japan.” Handbook of International Futurism, De Gruyter, Berlin, 2019, pp. 628–645.

Defining Futurism | Art History Unstuffed. https://arthistoryunstuffed.com/defining-futurism/.

Magazine, Smithsonian. “Futurism Is Still Influential, despite Its Dark Side.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 24 Apr. 2012, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/futurism-is-still-influential-despite-its-dark-side-74098638/.

Zanotti, Pierantonio. “A Popular Japanese Cartoonist Tries His Hand at the ‘Italian Futurists’ Painting Style’ (1913).” International Yearbook of Futurism Studies, De Gruyter, 2016.

Renkichi, Hirato. “Manifesto of the Japanese Futurist Movement: Hirato Renkichi.” CABINET /, https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/13/renkichi.php.

Leave a Reply