When I was growing up in high school, I was introduced to tons of different art movements through my classes or by my own discovery. The special few that I became inspired by were the surrealist movement and Dadaism in the 1910s-20s as well as the Avant-garde movement of the 20s. I was entertained by the ideas of uplifting your artistic potential with concepts of attentive dream theories, absurd whimsy, and the respectfully unorthodox and experimental. I believe that’s something that Kurt Schwitters of the 1920s alternative artistic scene did very well to portray in his work.

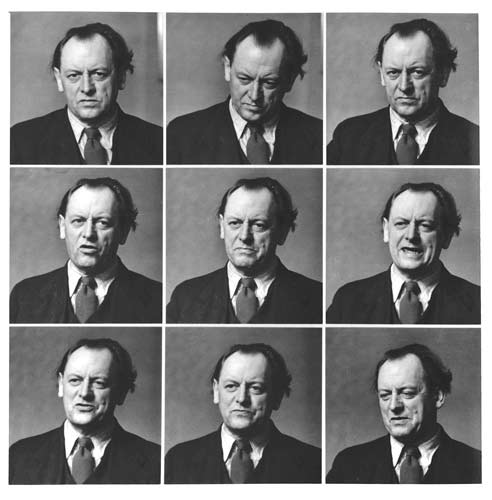

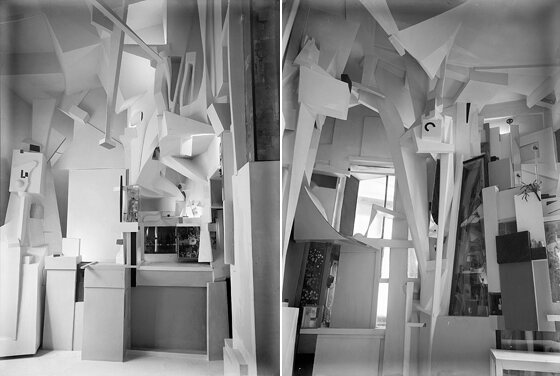

Kurt Schwitter (1887-1948) was a German Dada artist, poet and publisher that always worked to express his passion for the arts of any kind. It was the interest in collage making that inspired the Merz movement. The term he invented for his magazine is from the name of his most characteristic work in 1919, “DAS MERZFIELD” to call the collages he made from newspaper advertisements. Ultimately, Schwitters would use this medium to all his art activities and to the magazine he founded in Hannover in 1923. His style was made from collecting trinkets, junk, articles, old newspapers, pictures, string, wire etc and told his story of his feelings about art at the time. Schwitters also invented the Merzbau, which was a series of multimedia paper construction built into rooms of his house to look like an artistically surreal new world. Schwitters wrote many poems and articles in Merz. Some of them he called Merz Fairy Tales, which focused on ideas of full artistic freedom. art and stories in Merz desired to be creatively free from all restraints to shape things the way you intend to shape them artistically. Schwitter’s magazine also represented the idea that art can be anything and can have any kind of limitation, as long as the artist knows how to create.

He became highly appraised in the dadaist and surrealist movements, His old enemy finally debarred him from Dadaist activities and they became friends. As for the Nazis, when they came to power in 1933, they were offended by Schwitter’s visual artworks All of Schwitters’ fairy tales were considered provocative because the Nazis saw his work as “degenerate,” displaying as too abstract, too modernist and non-representational of any true German feeling or thinking.

That wasn’t the end of Merz yet. The magazine continued to live on in Europe where Kurt lived as a refugee from the regime. For a short time, Schwitters lived in Lysaker near Oslo in 1937, where he worked on a new Merzbau house (all of the Merzbau projects were unfortunately destroyed by the Nazis.) Later, when the Nazis again invaded him, he spent a short time in a nazi internment camp, then he fled to London, England in 1940 . Schwitters spent the last years of his life writing Merz Fairy tales and making more and more collages. He was highly regarded by the avant garde artists there and was immediately welcomed when he immigrated over. There he began work on a third Merzbau space, but it was far from completion when he died at 61. Today, art historians consider the work of the Merzbau and Merz magazine, a developed sub-genre of Dadaism.

References:

- “Schwitters Kurt (1887 – 1948).” A Biographical Dictionary of Artists, Andromeda, edited by Lawrence Gowing, Windmill Books (Andromeda International), 2nd edition, 1995. Credo Reference,https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/andbda/schwitters_kurt_1887_1948/0?institutionId=6884 . Accessed 23 Nov. 2022.

- Zipes, Jack. “Schwitters, Kurt (1887–1948).” The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales, edited by Jack Zipes, Oxford University Press, Inc., 2nd edition, 2015. Credo Reference, https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/oupoft/schwitters_kurt_1887_1948/0?institutionId=6884 . Accessed 23 Nov. 2022.

- “Merz.” A Dictionary of the Avant-Gardes, Richard Kostelanetz, Routledge, 3rd edition, 2019. Credo Reference, https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/routa/merz/0?institutionId=6884. Accessed 23 Nov. 2022.

- http://www.designishistory.com/1920/kurt-schwitters/

- Kłos, Anna. “Merz – Kurt Schwitters’ Combination of Art and Life.” Retroavangarda, Retroavangarda – International Project Promoting Artists Worldwide, 10 Dec. 2020, https://www.retroavangarda.com/merz-kurt-schwitters-2/.

- Shipe, Timothy. “Kurt Schwitters 1887-1948.” Encyclopedia of German Literature, edited by Matthias Konzett, Routledge, 1st edition, 2000. Credo Reference, https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/routgermanlit/kurt_schwitters_1887_1948/0?institutionId=6884. Accessed 24 Nov. 2022.

- Burns, Lucy. “Degenerate Art: Why Hitler Hated Modernism.” BBC News, BBC, 6 Nov. 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24819441.