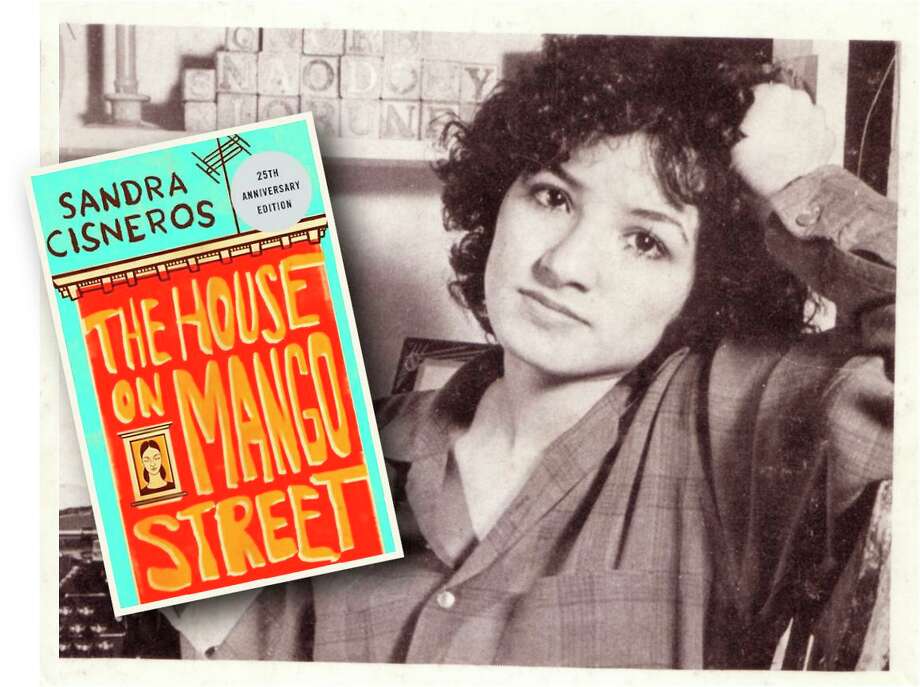

The final assignment for this class consisted of writing a book review on one of the course materials or authors. I selected Sandra Cisnero’s “The House on Mango Street” after we read “My name” essay in class because I felt identified with the author’s self-reflective voice, cultural background, and thematic interests. I also felt compelled by her ability to authentically write in a much younger voice than her own.

The House on Mango Street

Esperanza is a Mexican-American girl who lives in a house in Mango Street with her parents, brothers and sister. They have always lived in cohabitated spaces and Mango Street’s house is the first one they own and don’t need to share, but it’s not what Esperanza expected. By writing about the neighbours, friends, and the experiences she grew up with, in the last year on Mango Street, Esperanza finds a way to set herself free from all that she doesn’t feel like she belongs to while acknowledging she’ll always need to return for the ones that don’t get to escape their own reality. Her name, which she despises, ironically becomes what Esperanza is made of; her self-proclaimed destiny and responsibility towards her community: hope.

At glance, the House of Mango seems to be a pleasant compilation of sweet and innocent childhood memories told by the vibrant voice of a child in its purest form of expression and perception of the world around her. “Cats asleep like donuts”, laughter that sounds like “a pile of dishes breaking”, a “muddy colour” name, an old-man-soul’s garden that eats everything on top of it, and the perfect tree for the “First Annual Tarzan Jumping Contest” (Cisneros, 1997).

But as you keep reading, digging deeper into Mango street’s houses and their inhabitants, the underlying issues emerge. These are tales of shame, of scarcity, of fear, of nostalgia, of needing to pretend to fit in or dream of a different reality. Even when the speaker is not completely aware of the dangers and struggles that this place pose and its people –especially adults– go through, she knows there’s something particularly off with it and that is why the author chooses her as a speaker, an innocent but bright child who is able to say without really saying, through symbolism, metaphor, subtext, or a very literal and synesthetic description that enriches the world-building, while keeping the “language of speech” (Cisneros, 1997).

Every short story Esperanza tells works both as a self-reflection on a theme and as a portrait of the character it is about, creating a collage of complex humans that we see through Esperanza’s eyes and connect with beyond the superficial stereotype. It’s not just the childish woman out-of-touch-with-reality who lives with her mother, or the young Latino criminal that steals cars to impress others, or the crazy-delusional cat-lady on the attic, or the beaten-up-by-her-dad child, or the Rapunzel-like woman imprisoned by her husband, or the dead immigrant (XX) whose family can’t be traced. For Esperanza, they are Ruthie (Edna’s daughter), Louie’s cousin, Cathy Queen of Cats, Sally, Rafaela Who Drinks Coconut & Papaya, and Geraldo No Last Name (Cisneros, 1997). By naming them, Esperanza protects their humanity. By letting us know, not only their issues but how they feel about the situation they live in, their likes, fears, desires, regrets, longings… they become three-dimensional characters that we can understand and feel empathy for. And that is why Esperanza –and Cisneros, as the writer– bases her storytelling on the names of the people she describes, which in most cases give the title to the story. Some of the people appear more than once. Having to follow the intertwined stories of these characters obligates the readers to shift their view from a discriminative shallow visit to a precarious neighbourhood to a full submersive experience into Esperanza’s community.

What started as a memoir by Sandra Cisneros turned into a collective fictionalization of the truths experienced by “Others”; those who weren’t portrayed often and even less had a voice in the literary world when the author was growing up and when she finished her book (1982). Which, according to Junot Díaz hasn’t changed that much (Díaz, 2014). The author explains in the prologue why Esperanza narrates these tales we can all identify with and question our own identity from: “writing in a younger voice allowed me to name that thing without a name, that shame of being poor, of being female, of being not quite good enough, and examine where it had come from and why, so I could exchange shame for celebration” (Cisneros, 1997). That major theme of identity, and transformation from the shame of being “Other” into the celebration of being free, is shared with Ivan Coyote’s Rebent Sinner. Another thing both books have in common is the narrative structure, which goes from the narrator’s innocent childhood memories –getting gradually deeper into the social conflicts they’re denouncing– to a more self-aware present in which they can imagine a brighter future for themselves and the generations to come.

I was drawn to this book since we read the “My Name” story in class. It made me remember the way I spoke to myself and reflected about life when I was a child, when I started writing stories that I illustrated with play-dough, when I did gestures I hoped no one else watched because they wouldn’t get it, when I heard adults joke about things I didn’t understand but made them uncomfortable when I asked about them, when I heard my grandma gossip about the neighbours she later encountered and smiled to, when I kept a locked diary and hid the key in a box that I locked and placed that other key in a faraway drawer. I don’t even remember what I wrote about but I remember the shame I felt, the shame somehow I learnt to make mine. Some of us were lucky to live a relatively good and safe childhood that allowed us to be innocent for longer, but we all grew with some kind of internalized shame that holds us back until we learn how to harvest our own power from it. We might not be called Esperanza but we are all Esperanza and, as Cisneros reveals in her prologue –and The Three Sisters reminds us later–, we cannot forget who we are. (Cisneros, 1997).

Works Cited/ Consulted

Cisneros, Sandra. House On Mango Street. Jane Schaffer Publications, 1997.

Coyote, Ivan S. Rebent Sinner. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019.

Díaz, Junot. MFA VS. POC. The New Yorker, 30 April 2014. https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/mfa-vs-poc