The Idealistic Storyteller

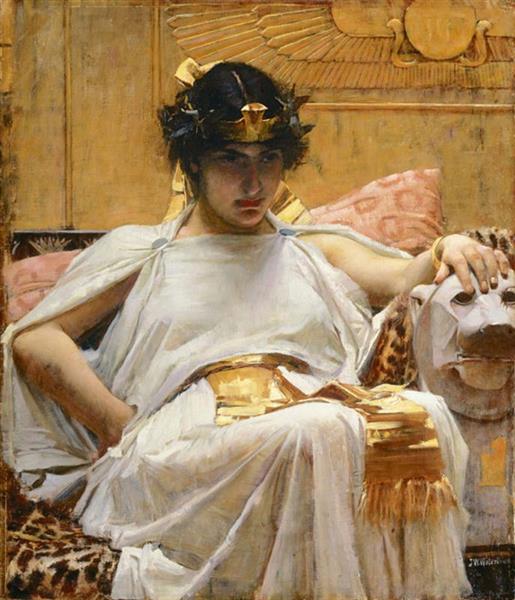

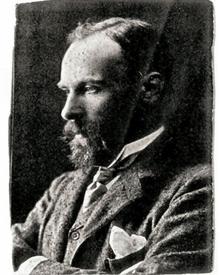

John Waterhouse has been called Pre-Raphaelite, but I think calling him a Romantic Classicist is perhaps more accurate. He had the Northerner’s love of legend and mystery, but his Italian birth lent him a warm personality to his renderings of classical myths, with people rendered as if they were superhuman beings. His work was no doubt influenced thematically by Pre-Raphaelites like Millais and Rossetti, among others.

Some of the Pre-Raphaelites, like Burne-Jones, managed to fix the image of pre-Raphaelitism in a mold of its own making – that of the long-haired girl in the long dress. But these girls are anonymous in most of his work and they lack the qualities of real people. Waterhouse’s paintings on the other hand, are sensitive and warm-blooded: they are actually the living models of his studio, with their own youth and their combination of modesty and sexuality imbued with the painter’s creative imagination. His characters reflect the perennial quality of the Greek legends, a strong Southern softness akin to Botticelli’s in which beauty is shared equally by good and evil and the only human differences are those of youth and age. There is no monsters in Waterhouse’s story-telling as in Dürer and even in some of the other Pre-Raphaelites and English Neoclassicists. He brought a refined sense of composition and the instant for the moment in the story at which everything seems to stands still. His art has a timeless quality, to a certain extent in accord with the fashionable taste both in his period and ours

John William was born in Rome and spent weeks of free wanderings and dwelling in Italian cities and country in his early years. He continuously returned during his life to experience anew the atmosphere of his boyhood. His father, William Waterhouse, was a Yorkshireman, an artist who practised with moderate success in prosperous Victorian society. Young William seemed to inherit his father’s talents. His mother, Isabella Mackenzie, and her younger sister Jane both exhibited portraits at the Royal Academy. At school in Yorkshire, a facility for drawing did not immediately prompt a career as an artist. It was a working apprenticeship in his father’s studio which eventually led to his entry to the Royal Academy Schools. His initial application to the Royal Academy Schools was rejected – specimens of drawings were to be submitted with the application and his drawing was rejected. He then decided to apply as a sculptor, submitting a model in clay and he was accepted in the Sculpture School in 1870.

It was the influence of a painter, F. R. Pickersgill, a Royal Academy member and his sponsor in the Academy, that was able to return the young Waterhouse to the field of painting.

Early Career

Early exhibition at the Winter Exhibition of the Society of British Artists in 1872 got Waterhouse noticed among the few whose pictures were accepted for their various qualities.

The following year the SBA’s Summer Exhibition included The Unwelcome Companion: A Street Scene in Cairo (1873). He used his friends and relatives, including his sister Jessie, as models. The Victorian compulsion to tell a story is quite obvious. He was developing the ability to compose a satisfying picture, but he had not yet acquired the combination of an appropriate setting with the pose and gesture of the figure which within a few years was to make him an outstanding illustrator of legends.

Some of these early pictures have no story to tell: they owe their charm to the sensitive painting of the female figure, as in La Fileuse, The spinner (1872) and An Eastern Reminiscence (1874). His paintings, however, continued to appeal by their individual subject matter. His favorite model at this time may well have been his sister. It should be recalled that all this took place while Waterhouse was still a student.

The Dudley Gallery’s Winter Exhibition of 1874 included Waterhouse’s In the Perystile. It showed the next major influence on him – that of Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who had settled in London with a European reputation. However, Waterhouse consistently painted on a larger scale than Alma-Tadema. His brushwork is bolder, his sunlight casts harsher shadows and his story paintings are more dramatic. Alma-Tadema’s careful research and the rendering of architectural interiors with their figures in classical dress were an inspiration to many students.

Waterhouse’s first Royal Academy exhibit, however, also in 1874 diverged from the classical theme and showed considerable depth of feeling. Sleep and his Half Brother Death relates quite certainly to family tragedy: his mother and his two younger brothers had succumbed to tuberculosis.

Waterhouse’s returned to Italy for periods of travel and study between 1876 and 1883 and produced a number of charming pictures, showing his interest in colour and the play of light. Typical is the picture of Two Little Italian Girls by a Village (1875). However, his thoughts were ever with the beings of history and mythology rather than with fisher folk and farmers. Examples of pictures of this period are After the Dance and A Sick Child brought into the Temple of Aesculapius (1877) which he exhibited at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1877.

No doubt the inspiration of those works came largely from Alma-Tadema, but the differences not merely in size but in depth of subject are already apparent, and Waterhouse finally decided to leave the train of the famous master at a peak of his own achievement. The 1882 Diogenes (82x53in), precise in its rendering of architecture and the texture of the marble linked to the figures of the girls so unaffectedly posed represent a perfect composition.

It was then that Waterhouse turned in 1883 to the old Empire for his first major exercise in history with The Favourites of the Emperor Honorius (46x79in). The emperor and his pets – the ‘favourites’ – occupy a space of their own, defined by the darkness of the carpet and his garments, The central figure of the attendant is stiffened in posture, turned away, reduced to the scale of the councillors, who wait tensely, with eyes anxiously fixed on the emperor. The moment of stillness captured on the canvas is a clear mark to Waterhouse’s artistic genius.

Of this period are also: Consulting the Oracle (47x78in), which established Waterhouse as a classical painter, with use of classical, geometrical structures of Greek temples, and St Eulalia (74x46in). The whole force of the picture is centered in the pathetic dignity of the outstretched figure, beautiful in its helplessness and serenity. The potent and effective simplicity, its direct and touching language needs no interpreter.

Later Career

Waterhouse was elected to Associate of the Royal Academy in 1885 and in 1893 he was proposed for full Membership. In 1895 he was elected as full Academician. Waterhouse was now firmly established in the ranks of the Royal Academy and in favour with both critics and public. Hylas and the Nymphs belongs to this period, also Pandora, which appeared in the Academy exhibition of 1896. The following year he showed Mariana in the South at the New Gallery, a haunting picture of Tennyson’s desolate maiden. Waterhouse’s lovely girl conveys all the heartfelt message of the lines: ‘Low on her knees herself she cast’, And on the liquid mirror glow’d/The perfection of her face’.

The Rose Bower, Penelope and the Suitors, The Sorceress and The Danaides are some of the latest Waterhouse’s works.

The patronage of the Henderson family, the financier and his brothers, was perhaps the most important of Waterhouse’s career. Portraits of members of the Henderson family: Lady Violet Henderson, Miss Margaret Henderson and Mrs A. P. Henderson are witness of the genuine friendship of Waterhouse with the Henderson family.

Waterhouse’s paintings have a virtually universal appeal: they are inhabited by beautiful people and recall well-known stories of personal situations. In spite of his Italian birth and sympathies, his paintings are strongly English in spirit. Over and above the question of style, is Waterhouse’s narrative ability. He was in tune with the tales he chose as to extend their literary imagery by his own invention filling the spaces of our imagination in a manner so natural that we feel it could hardly be otherwise.

Sources

- “John William Waterhouse – Style and Technique’. www.artble.com

- www.john-william-waterhouse.com

- Gunzburg, Darrelyn (2010) ‘John William Waterhouse, Beyond the Modern Pre-Raphaelite’, Art Book 17

- Trippi, Peter (2002) ‘J.W.Waterhouse’, New York, Phaidom Press

- Images: https://www.wikiart.org/en/john-william-waterhouse