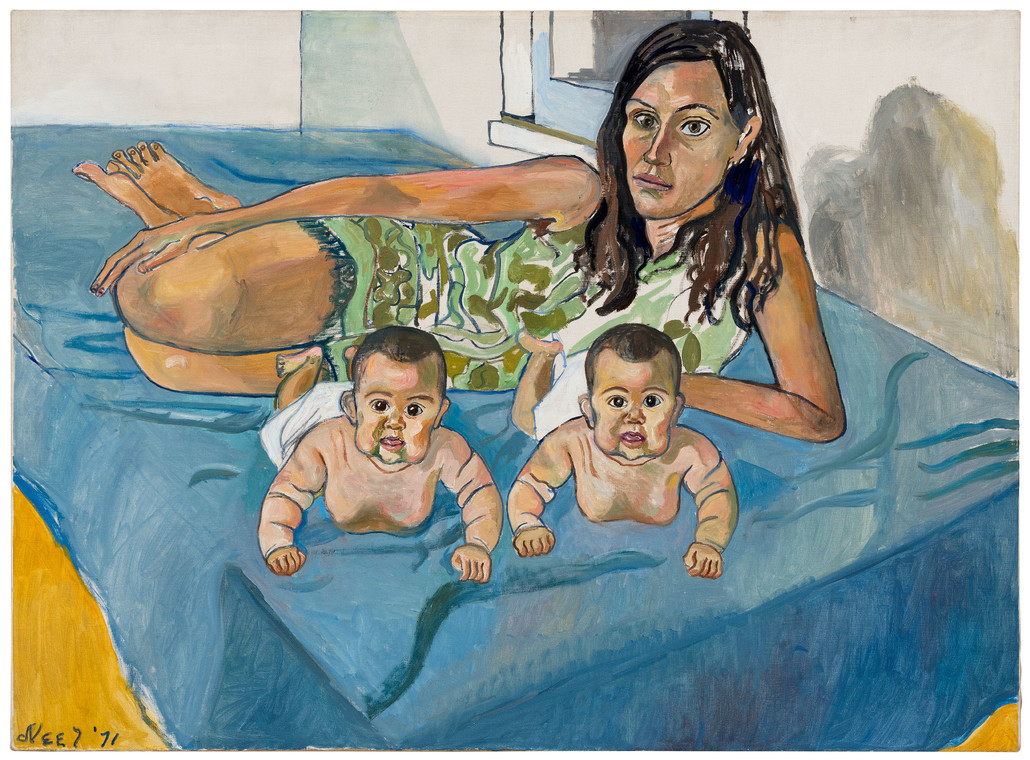

Promotional poster for Alice Neel: A Biography.

Alice Reel’s artistic career and personal life is indeed fascinating. She was born in Merion Township, Pennsylvania on January 28, 1900, the fourth of five children. Her father George Washington Neel, was an accountant and her mother, Alice Concross Hartley was a descendant of politically distinguished ancestors. When Alice was still a toddler the family moved to Colwyn, Pennsylvania, a small town outside Philadelphia in Darby Township where she attended primary school and high school. As part of her high school curriculum Alice took some secretarial courses and after graduating from high school in 1918, she took a secretarial job with the Army to help support her family. She worked there for three years while taking evening classes at the School of Industrial Art in Philadelphia.

After saving some money and with the help of scholarships, she enrolled at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women. She was an exceptional student winning a multiple awards for the work she did. She studied under two well known American artists: Henry Snell, associated with the New Hope, Pennsylvania School of landscape painting, a painter of coastal scenes, and Rae Sloan Bredin, of the Pennsylvania school of impressionists, known for his portrait paintings and summer landscapes with groups of women and children. Alice received extensive art instruction in landscape painting and portraiture from those artists, a training that was to define Neel’s future art career.

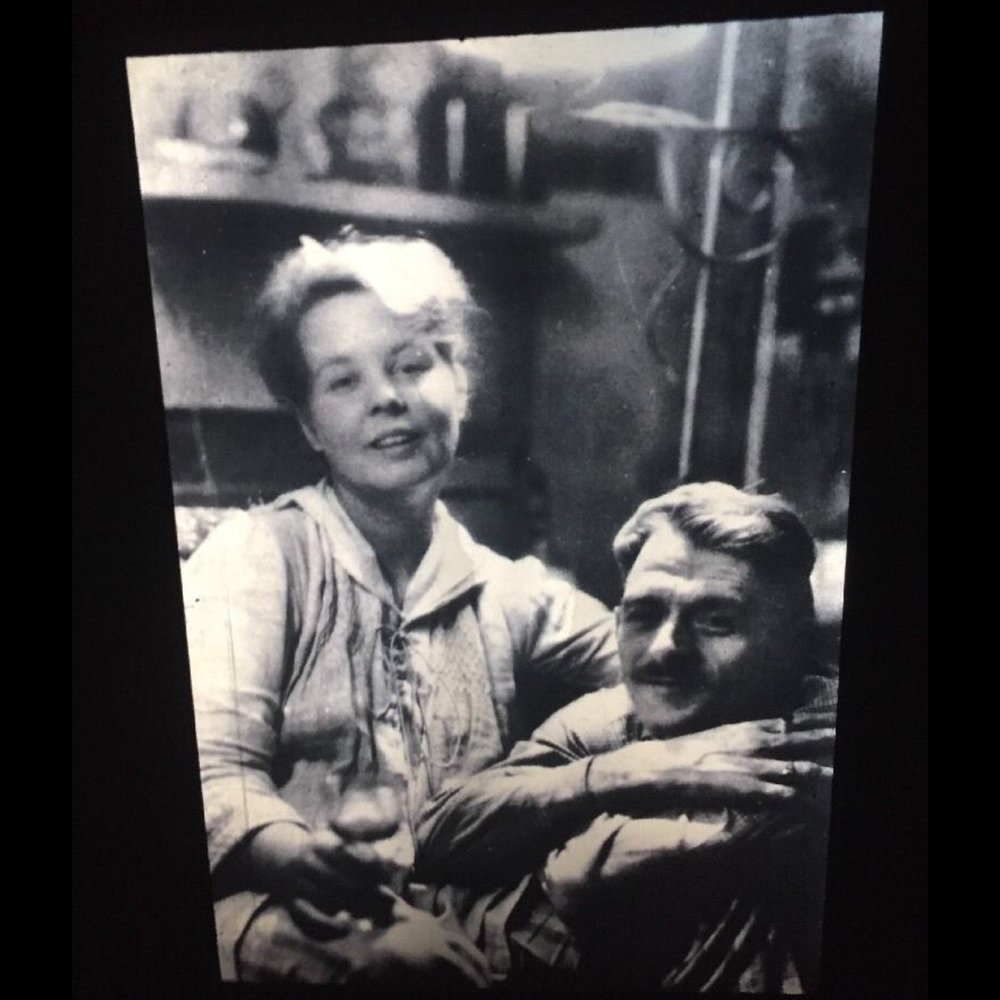

1924 was the year that radically changed Nell’s personal life. She attended a summer school program with the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Chester Springs, Chester County, Pennsylvania, and it was there that she met a Cuban wealthy student, Carlos Enriquez. She fell in love with him and they got married soon after in Colwyn in 1925. At the end of the year they moved to Havana, Cuba.

In 1926 Neel had her first solo exhibition in Havana. She also had her first child, Santillana del Mar, who succumbed to diphtheria soon after, while still an infant. Neel’s experience in Havana between 1926 and 1927 forged her ideas about art. The political situation in Cuba under the dictator Gerardo Machado was precarious at best. Although Enriquez’s parents lived in a prosperous suburb of Havana, Carlos and Alice took trips into the city to paint portraits of people from the lower classes. After a while they left Carlos’ parents household and moved to a deprived neighbourhood, La Vibora, where left-wing writers and artists lived. Here Neel had a chance to meet some of those writers like Nicolás Guillén, Marcelo Pogolotti and Alejo Carpentier. She discovered through their writings that art could be used as a political messenger. She became aware of the power of art and literature to affect society in the process of change. She discovered through their books how American foreign policies in Latin America had impacted the lives of people and prompted Neel to share their anti-American sentiments.

Carlos and Alice ended up moving back and forth for a while between Havana and the US but they eventually decided to settle in the US. They moved to Manhattan Upper West Side and they had another child Isabetta. They thought about moving to Paris for a while but that never materialized. However, for some reason, Carlos, unexpectedly, decided to move to Paris and took Isabetta with him and leave her with his family in Europe. Neel had a nervous breakdown and was briefly hospitalized. She went to Europe to find her husband in an attempt to save the marriage. After realizing the relation was over she attempted suicide several times and ended in a psychiatric hospital for treatment. She never saw Carlos again and Isabetta only a few times in her life.

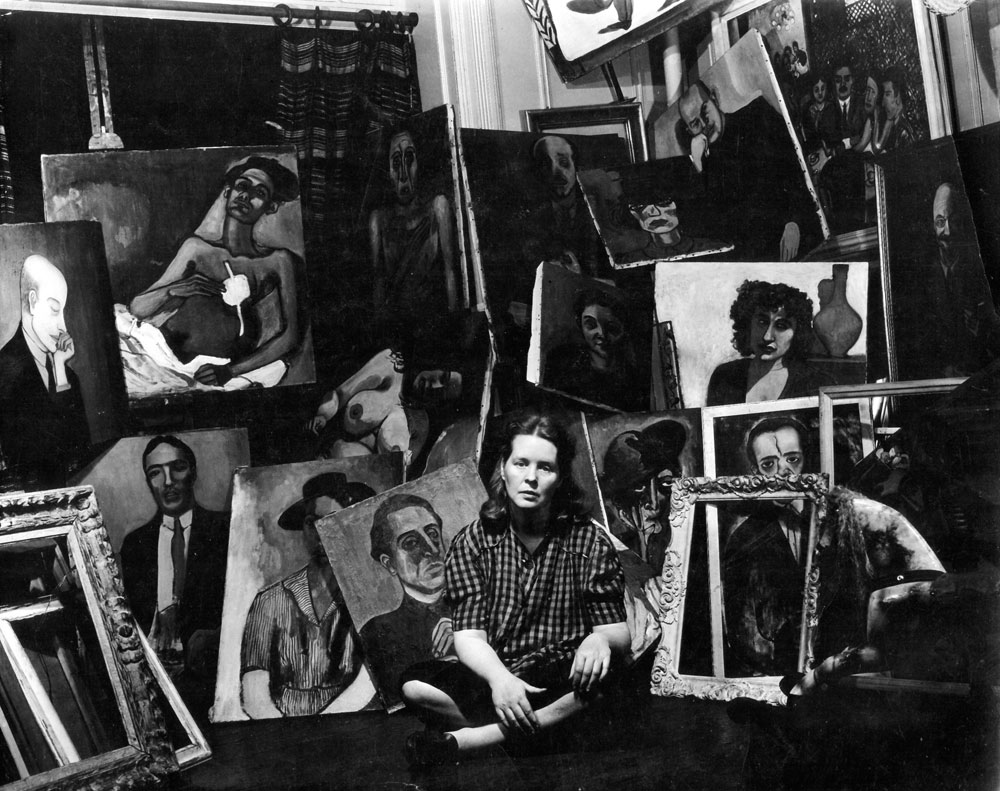

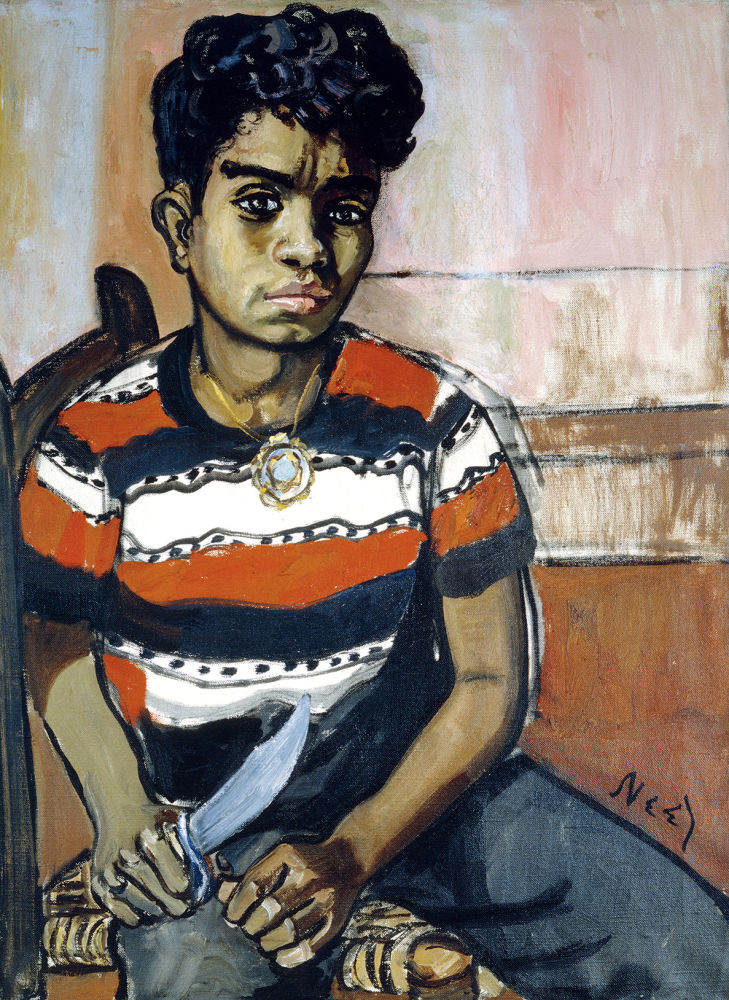

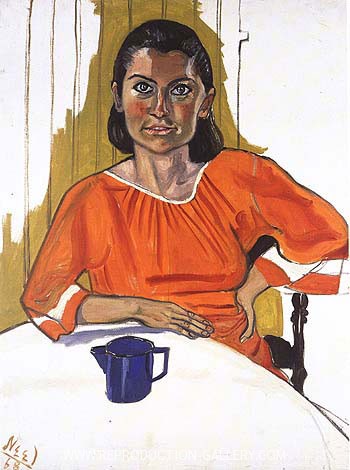

Back in the United States, Neel moved to Greenwich Village. 1931 was an interesting time to live in this part of town. She made efforts to reintegrate into the art world. As a consequence of the Great Depression a lot of intellectuals and writers who lived through it became interested in Marxism and became politically active. It was in this urban setting that Neel started to produce “revolutionary art”, mostly portraits. A departure connected with the turn to Marxism of writers and intellectuals of her acquaintance, and became involved with the Artists’ Union, an organization of radical artists and writers to further cultural opportunities for the American working class In 1935 she became a party member and although she remained committed to Expressionist techniques, she used them in conjunction with a documentary conception of arts function that had a wide acceptance on left circles. She left Greenwich Village for Spanish Harlem in 1938 to get away from the rarified atmosphere of an art colony. She painted the Puerto Rican community, neighbours and people she encountered in the streets. Neel’s primary impulse behind ‘pictures of people’ was to serve as a social and historical record of her times. Her works recall American documentary photographers like Berenice Abbot, Dorothy Lange and Hellen Levitt.

From 1951 to 1955 she was under investigation by the FBI who described her as a “romantic Bohemian type Communist”. Two agents visited Neel’s house in 1955 to interview her. The accepted anecdote is that after the interview, Neel supposedly asked them to sit for a portrait but they declined.

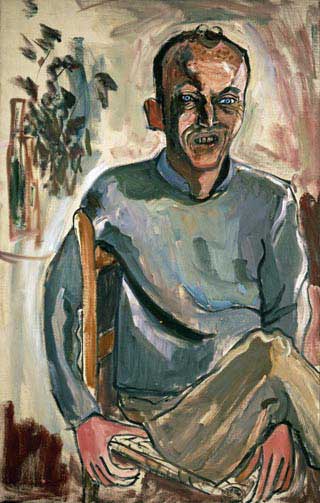

The chosen subjects for her portraits consisted mostly of leading Communist figures like ‘Mother’ Bloor (Ella Reeve), founding member of the Social democracy of America, proletarian writers like Sam Putnam, Joe Gould and Max White and her artistic friends, journalists and poets. For Neel, the Communist activists she painted were heroes.

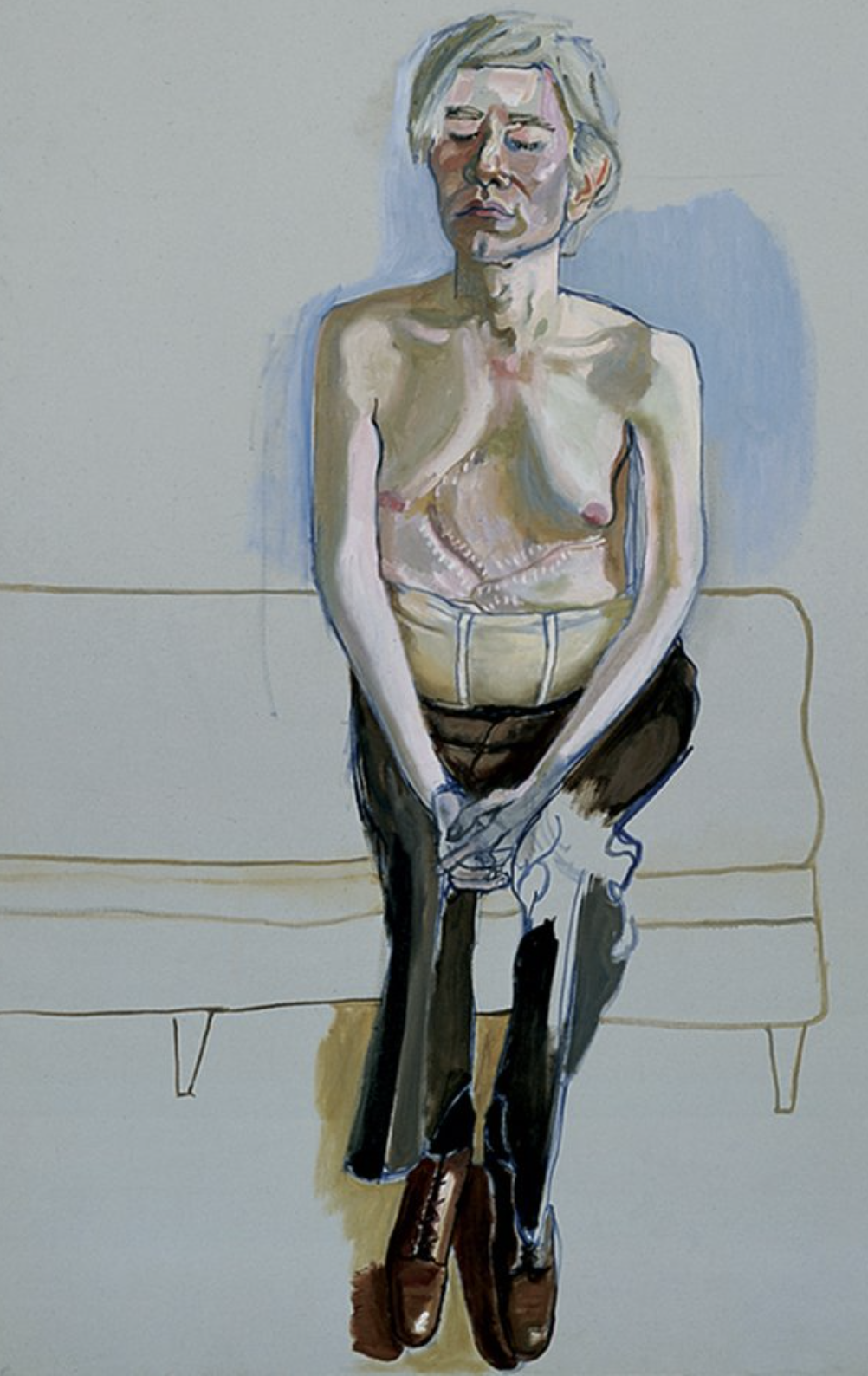

In the 1960s she moved to the Upper West Side and made efforts to reintegrate again into the art world. From this time are the portraits of artists, curators and gallery owners, among them Frank O’hara, curator at MOMA, Andy Warhol and Robert Smithson, political personalities like Ed Koch, mayor of New York and also political activists and supporters of women’s movement.

She continued to live in New York and thanks to the Works of America Project, she received funding in 1933 through one of the initiatives enacted under President Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Works Progress Administration (WPA). During the Depression Neel became an activist for left-wing political causes and the WPA continued to support her until 1943. Thereafter, she really straggled to make ends meet for the rest of the 1940s. In 1944, she even bought back some of her own paintings that were sold to a Long Island junk dealer. At one point she had to depend on welfare to be able to survive.

In the 1950s and 1960s Neel saw the rise of the Abstract Expressionism in New York (Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline) but she remained wholly committed to representational work. She was interested in real people, not just bohemians and fellow artists. Her portraits of the 1950s capture the characters of her friends and neighbours in New York’s Spanish Harlem with careful expressionistic detail.

To a reporter of Daily Worker – the newspaper published by the American Communist Party, she declared:’ I am against abstract and non-objective art, because such art shows a hatred of human beings …and I am on the side of people there, and they inspire my paintings…’2

She believed that once the subject was at ease in front of the easel he/she would adopt their most characteristic attitudes: ‘…before painting, when I talk to the person, they unconsciously assume their most characteristic pose, which in a way involves all their characters and social standing – what the world has done to them and their retaliation’3. Her sitters in the portraits always appear in the almost neutral space of the studio, with no sign of their status or social selves but their choice of clothes and their physical features. Neel worked with great detail on their faces because in her view the face shows everything: their inheritance, their class and profession, their feelings and their intellect. All that is happening to them in life. What is really impressive about the portraits of people like the labour journalist Art Shield and the Ford union organizer Bill McKie, is that they almost look like homages to van Gogh

She saw her ‘pictures of people’ as opposing the process of dehumanisation and that is how her exhibits of 1950-51 were presented in the Party press. So many of the painting she showed in those years represented the working class of Spanish Harlem, where she lived from 1938 to 1962. Neel’s primary impulse behind those ‘pictures of people’ was to serve as social and historical records of her time. They recall the pictures of the American documentary photographers of the 1930s and 1940s: Berenice Abbott, Dorothea Lange and Helen Levitt.

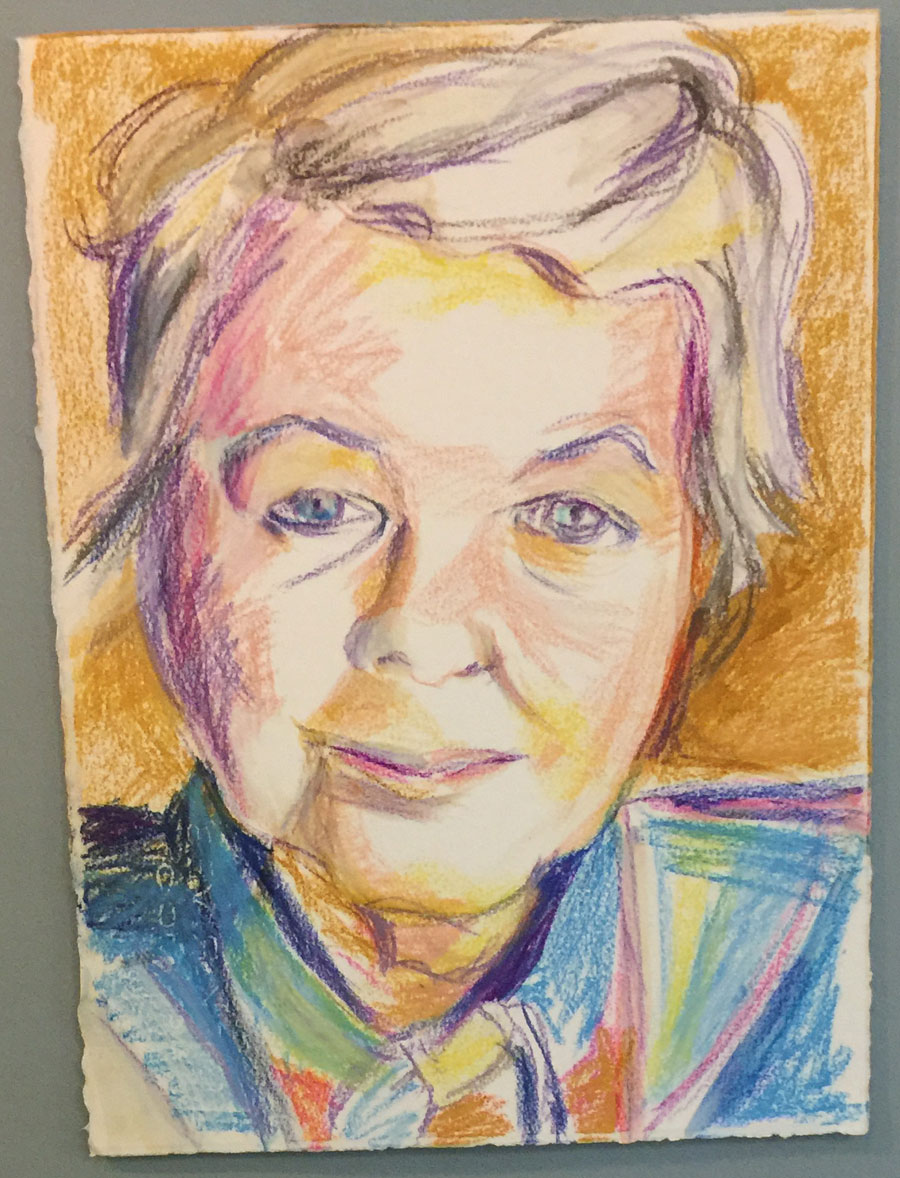

She developed her own variant of Expressionism with a particular use of colour and lines, in part to present herself in later life as one-of-a-kind Expressionist artist. She achieved a consistent level of professionalism without sacrificing the original qualities of her work when her career took off in the early 1960s. Although Neel saw herself as a realist, she also self consciously saw herself as a modern. In 1977 she declared: ‘I never followed any school and I never imitated any artist’4.

Andy Warhol by Alice Neel (1970)

In 1955 Neel began attending meetings of the Club, an artist discussion group founded by artists who had rejected the traditional art practices. In 1959 Neel acted along a prominent writer of the Beat generation, Allen Ginsberg in ‘Pull my Daisy’, a shot film based on a play by Jack Kerouac. She maintained the friendship through the years.

She remained an artist of the left, like some of the other artists and writers, and her reputation as an artist suffered in part because of her Communist politics. Also that commitment of artists and writers to a ‘humanistic art’ however, put them at odds with their times, their attachment to the human figure made them appear as upholders of traditional artistic skills no longer in vogue and somehow followers of old-fashioned aesthetics. However, after the Cold War thawed sufficiently, and the ‘red scare’ subsided, her merits and the importance of her contributions to a socially concerned art in the US were finally acknowledged.

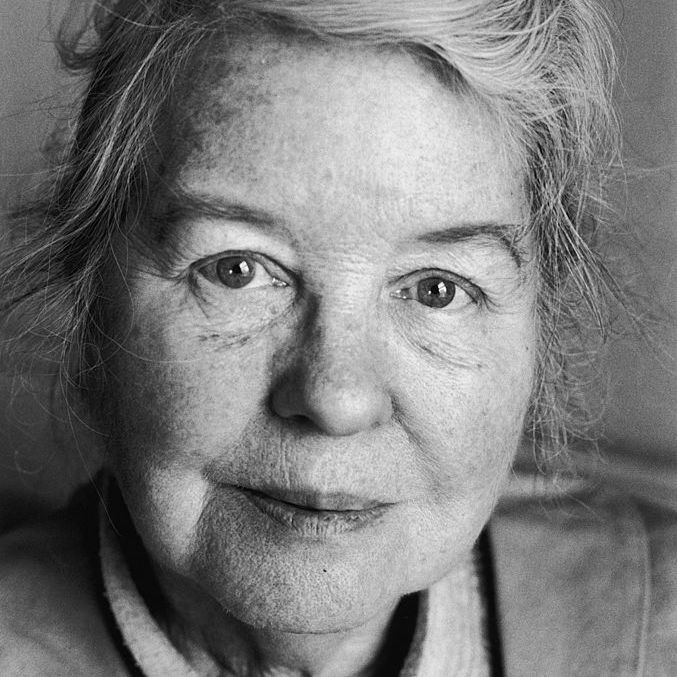

She has done the work of a whole generation of artists who were afraid for their lives as artists if they were to portrait the conditions of the society they lived in. It is worth noticing that Neel was virtually unknown and had only a few solo shows prior to 1970. In the last two decades of her life however, she had sixty.

In 1981, eighty-five of her works were shown at the Union of Artists of the USSR exhibition hall in Moscow. Interesting enough, an exhibition display partially financed by her.

She was underappreciated for years, but by the end of her life she had gained a bit of fame and public recognition. In 1979 she was given an award by President Jimmy Carter, for outstanding achievement and in 1982 she became the first living American artist to have a major retrospective exhibition in Moscow.

Neel was extremely well read (Auden, Proust, Joyce, Hemingway…). Her breath of intellectual interests, literary, .philosophical and artistic help explain the number of writers, art historians, and critics she befriended and painted throughout her artistic life. Artists Andy Warhol, Duane Hanson, art historian Mayer Schapiro and Linda Nochlin. Composer Virgil Thompson and Nobel Prize laureate Linus Pauling.

Alice Neel passed away on October 13, 1984, her legacy well established and fully acknowledged by both the public and the art world. At the memorial service for Neel, Allen Ginsberg performed the first public reading of his poem ‘White Shroud’ as a tribute to her.

“I have always believed that women should resent and refuse to accept all the gratuitous insults that men impose upon them.” -Alice Neel

Footnotes:

- Hemingway, A. (op.cit.) p.248

- Hemingway, A. (op. ct.) p.250

- Auerbach, F. (op.cit.) p.93

- Lewison, J. ‘Beyond the Pale’

Sources:

Adams, Tim, “Meet the neighbours: Alice Neel’s Harlem portraits“, The Observer, April 29, 2017.

Auerbach, Frank “Artist Appreciations”, in Alice Neel: Painted Truths, eds. Jeremy Lewison and Barry Walker. New Haven: Yale University Press 2010, p.93

Bauer, Denise. Alice Neel’s Feminist and Leftist Portraits of Women. Feminist Studies v.28.

Hemingway, Andrew. ‘Artists on the Left’. American Artists and the Communist Movement 1926-1956. New Haven and London: Yale University Press 2002, p.247-52

Lewison, Jeremy. ‘Painting Crisis’, ‘Alice Neel, Painter of Modern Life’, exhibition catalogue, published by Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Yale University Press, 2010

Lewison, Jeremy. ‘Beyond the Pale’, ‘Alice Neel and her legacy’, Arts & Australia, vol.48 no.3, February 2011

Stamps. Laura. ‘Alice Neel, a Marxist Girl on Capitalism’, Alice Neel, Painter of Modern Life, exhibition catalogue, published by Ateneum Art Gallery, Finnish National Gallery, Brussels 2017.

Tamar, Garb. “The human race turn to pieces: the Painted portraits of Alice Neel ”, in Alice Neel: Painted Truths, eds. Jeremy Lewison and Barry Walker. New Haven: Yale University Press 2010, p.18

Alice Neel latest solo exhibitions:

2000 Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

2004 A Chronicle of New York. Victoria Miro, London.

2005 Alice Neel’s Woman. National Museum of Women’s in the Arts, Washington, DC.

2007 The Cycle of Life. Victoria Miro, London.

2007 Pictures of People. Aurel Scheibler, Berlin.

Documentary:

2007 Alice Neel: A biography – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZObd29Jv8ks

Latest group exhibitions:

1999 In memory of my Feeling: Frank O’hara and American Art. Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

2001 The Human Factor: Figuration in American Artt. Contemporary Art Centre of Virginia, Virginia Beach.

2007 Wack ! Art and the Feminist Revolution. The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, Los Angeles.