Personal History and Artistic Training

When Millet was 18 (1833), he went to Cherbourg to study with the portrait painter Paul Dumouchel. He stayed here and studied with Lucien-Théophile Langlois, a pupil of Baron Gros, until 1837 when he moved to Paris. There he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts with Paul Delaroche, and In 1839 his first submission to the Salon was rejected.

When a portrait of his was accepted at the Salon in 1840, Millet returned to Cherbourg to work as a portrait painter. In 1841, he married Pauline-Virginie Ono, and they moved to Paris together. Multiple rejections at the Salon in 1843 and his wife’s death by consumption (tuberculosis) compelled Millet to return to Cherbourg. Millet moved to Le Havre with Catherine Lemaire in 1845, and he married her in 1853. Here he painted portraits and small genre pieces for several months, then returned to Paris.

In the 1840s in Paris, Millet became friends with Constant Troyon, Narcisse Diaz, Charles Jacque, and Théodore Rousseau. Like him, they would become associated with the Barbizon school. He also befriended the artist Honoré Daumier, and was influenced by his figure drawings, as well as Alfred Sensier, a government bureaucrat who would become Millet’s lifelong supporter and later the artist’s biographer. Millet’s first Salon success came in 1847 with the exhibition of a painting Oedipus Taken down from the Tree, and in 1848 his Winnower was bought by the government.

Millet’s most ambitious work at the time, The Captivity of the Jews in Babylon, was unveiled at the Salon of 1848. However, it was disliked and mocked by art critics and the public. The painting disappeared shortly afterwards, and historians believed that Millet destroyed it until 1984 when an x-ray of Millet’s painting The Young Shepherdess (c.1870) revealed that Millet had painted this work over Captivity. It is thought that he reused canvases when materials were scarce during the Franco-Prussian War.

His Time at Barbizon

Millet continued to paint commissions for the state and tried to please the salon until 1849, when he settled in Barbizon with Catherine and their children and started to favour a more personal and realistic approach to his painting.

Millet revolted against the academic idea that ‘dignified paintings must represent dignified personages’, and that workers or peasants weren’t fit for representation in scenes other than those in the tradition of the Old Dutch masters. Around 1848, a group of artists under the influence of Constable gathered in the French village of Barbizon to look at nature with fresh eyes. Millet decided to further to incorporate figures into this programme. He wanted to paint scenes from peasant life as it really was, to paint men and women working in the fields. This should have been considered as revolutionary at the time, since the art of the past mainly depicted peasants as comic yokels.

In 1850, Millet exhibited Haymakers and The Sower, at the Salon. This is considered his first major masterpiece, and is the earliest painting from his most famous three that would include The Gleaners and The Angelus.

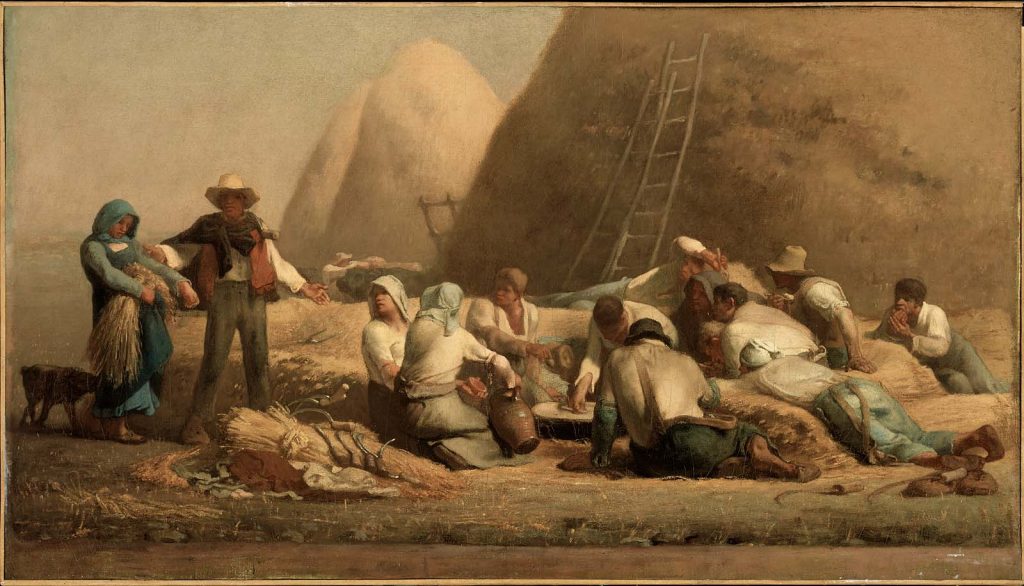

Millet worked on Harvesters Resting (Ruth and Boaz) from 1850-1853, the longest he would work on a painting. He considered this painting as his most important. It was made to rival the work of his inspirations Michelangelo and Poussin, and it was the piece that initiated Millet’s move from depicting symbolic imagery of peasant life to that of ‘contemporary social conditions’. This work was the only one he ever dated, and was the first painting of his to gain him official recognition in the form of a second-class medal at the 1853 salon.

His Impact on the Future

Millet and his work served as a source of inspiration for many artists and writers that came after him. Vincent van Gogh, especially in his early work, was very inspired by Millet. Van Gogh often mentioned the older artist and his work in his letters to his brother Theo. Millet’s later landscapes also served as reference to Claude Monet’s paintings of the coast of Normandy, and Millet’s ‘structural and symbolic content’ was an influence to Georges Seurat as well.

The main protagonist of Mark Twain’s play Is He Dead? (1898) is Millet, in which he is depicted as a struggling young artist who resorts to faking his own death to score fame and fortune. Most of the aspects of the play are fictional.

Edwin Markham’s famed poem “The Man With the Hoe” (1898) was inspired by Millet’s ‘L’homme à la houe’ . Markham’s poems in turn served as the inspiration for the later poet David Middleton’s collection The Habitual Peacefulness of Gruchy: Poems After Pictures by Jean-François Millet (2005).

Millet’s masterpiece the Angelus was often reproduced during the 19th and 20th centuries, and captivated the surrealist Salvador Dalí. He wrote an analysis of it, The Tragic Myth of The Angelus of Millet, in which rather than seeing the painting as a work of spiritual peace, he theorized it held messages of repressed sexual aggression. Dalí also thought that the two figures were actually parents praying over their burial site of their child, rather than to the Angelus. His fervour led to and x-ray being done of the canvas, the results of which confirmed his suspicions: the painting contains a painted-over geometric shape strikingly similar to a coffin. Millet’s intentions regarding the shape remain unclear.

Cited:

Wikipedia, Jean-François Millet: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Fran%C3%A7ois_Millet

Wikipedia: L’Homme à la Houe: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jean-Fran%C3%A7ois_Millet_-_L%27Homme_%C3%A0_la_houe.jpg

EH Gombrich, The Story of Art, pp. 508-510

Encyclopedia Britannica: Jean-François Millet: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Jean-Francois-Millet-French-painter-1814-1875

Coralie,

Excellent work on both Reynolds and Millet. I can’t say enough about your research and personal insight gleaned from that research. Your writing is exemplary, clear and informative. A pleasure to read. Keep it up.

Just a note that your post on #6 Impressionism and Post Impressionism are overdue.

Jeff

Whoops, just realized that my Impressionism blog post failed to upload because my images were too big. Thanks for letting me know, and I’m glad you’re enjoying the blog! 🙂