Introduction & Overview

Officially called the Republic of Korea (ROK), South Korea has a population of 51,418,100 people, with 81.4% living in urban areas and an annual the rate of urbanization of 0.3% (CIA, 2019). In the early 1960s, South Korea’s economy was mostly agricultural and had a very low level of GDP per capita (Bamber, 2015). Through a policy of export-oriented industrialization, a series of economic development plans rapidly transformed the nation.

This led to great success: with annual export growth of 30% and annual GDNP growth of more than 8% (Bamber, 2015), South Korea gained entry into the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 1997 (CIA, 2019). The government’s policies were responsible for determining how financial capital would be allocated and how industrial technologies would be applied. This promoted chaebol (conglomerates) as partners of its development, such as Hyundai and Samsung (Bamber, 2015). These chaebol continue to hold dominant positions in Korea’s economic structure today.

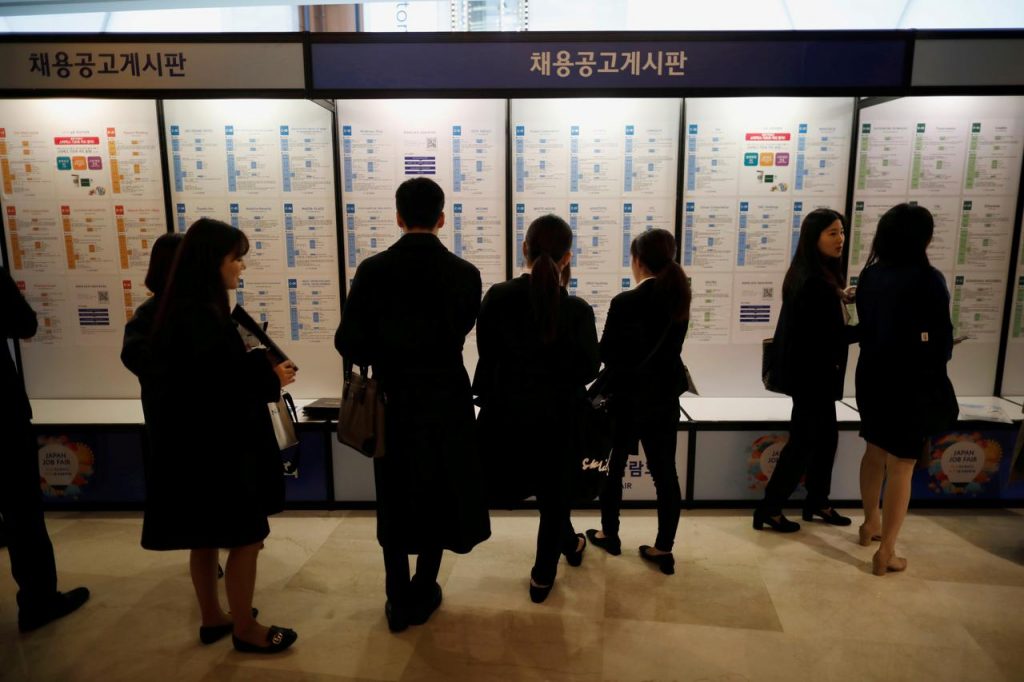

Education is highly valued in South Korea: two-thirds of those between the ages of 25 and 34 hold a college degree (Tai, 2018). This workforce is well educated, has high career expectations, and prioritizes opportunities for career development and advancements (Strother, 2012). Because so much of its population is so highly qualified, the environment is very competitive for those seeking top-tier jobs. To help ensure jobs for its citizens, the government has designed programs to place South Koreans in jobs outside the country, particularly to Japan (Yang and Kim, 2019).

Recruitment Practices

According to the Labour Standards Act, employers may not discriminate against workers by their nationality, religion, social status, gender, or age (Brown, 2012). Gender equality is further addressed in the Equal Employment Act (EEA), detailing the terms of employment, wages, and working conditions. Violations of the EEA can result in a fine of 10 million Won or prison time; however, discrimination against women still persists. For example, women in non-agricultural industries earned 63% of what male workers earned in 1999. Within the manufacturing sector, women earned 55% of male earnings.

Referral Network

It is common to recruit through relationships and networks, particularly yongo, which are informal networks based on shared school affiliation, regional origin, and family (Horak, 2017). Aside from school-based ties, membership within each yongo is exclusive and based on predetermined circumstances. Those without an influential yongo have fewer chances to improve their careers and economic situations, which is why there is such a strong demand for higher education. However, the importance of these networks has been changing because of the increased need for skilled employees with specialized competencies (Horak, 2017). Smaller companies tend to rely less on external recruitment and more on yongo, especially for blue-collar workers and in rural areas of the country (Chandrakumara, 2013).

Recent Graduates

Many companies prefer to hire new graduates and will not consider those who have graduated even two or three years earlier. There is a belief that young and inexperienced employees will be easier to train, can learn faster, and will be able to stay with the company for longer (Gross and Connor, 2018). The top Korean universities will typically host two student recruitment sessions per year at their campuses (Gross and Connor, 2018).

Selection Practices

Many white-collar jobs in South Korea require applicants to pass extensive employment exams (Tai, 2018). According to an individual looking to work in journalism, the company asked for a completed application, two essays, and a two-hour test on subjects including sociology, economics, politics, and Chinese writing (Tai, 2018). There was even a test to examine the applicant’s behaviour after having an alcoholic beverage with the hirer. After advancing to the next level, job seekers must pass another series of tests. Applicants are not compensated for their time and are not guaranteed employment.

Within the government, hiring targets have been established regarding gender, disabilities, and lower levels of income (OECD, 2012). For example, if less than 30% of one gender has passed the recruitment examination, additional applicants from that group will be added. There is also a 1% quota for new recruits to be from lower income backgrounds and 3% for people with disabilities.

Miscellaneous Information

Despite the mismatch of supply and demand for high paying white-collar jobs, there is also an acute shortage of blue-collar workers, as they are perceived as low-level and degrading (Yang and Kim, 2019). In order to bridge this gap, foreign workers are brought in from the Philippines, China, and Vietnam.

Bibliography

Bamber, G. (2015). International and comparative employment relations. 6th ed. London: SAGE, pp.266-290.

Brown, R. (2012). East Asian labor and employment law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chandrakumara, P. (2013). Human resources management practices in small and medium enterprises in two emerging economies in Asia: Indonesia and South Korea. In: Annual SEAANZ Conference. [online] Sydney: Small Enterprise Association of Australia and New Zealand, pp.1-15. Available at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1417&context=gsbpapers [Accessed 16 Oct. 2019].

CIA (2019). Korea, South — The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency. [online] CIA. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ks.html [Accessed 25 Oct. 2019].

Freepik (n.d.). Seoul city view. [image] Available at: https://www.freepik.com/premium-photo/sunset-63-building-seoul-city-south-korea_2269565.htm [Accessed 25 Oct. 2019].

Gross, A. and Connor, A. (2008). HR, Recruiting Trends in South Korea. [online] SHRM. Available at: https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/global-hr/pages/hr,recruitinginsouthkorea.aspx [Accessed 20 Oct. 2019].

OECD (2012). Korea. Human Resources Management Country Profiles. [online] OECD. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/OECD%20HRM%20Profile%20-%20Korea.pdf [Accessed 13 Oct. 2019].

Reuters (2019). South Korea’s latest big export: Jobless college graduates Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-jobs-kmove-insight/south-koreas-latest-big-export-jobless-college-graduates-idUSKCN1SI0QE [Accessed 25 Oct. 2019].

Reuters (n.d.). Young Koreans looking at bulletins. [image] Available at: https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.reuters.com%2Farticle%2Fus-southkorea-japan-jobs%2Flabor-pains-japanese-jobs-for-south-korean-graduates-dry-up-amid-trade-row [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

Strother, J. (2012). Drive for education drives South Korean families into the red. [online] The Christian Science Monitor. Available at: https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Asia-Pacific/2012/1110/Drive-for-education-drives-South-Korean-families-into-the-red [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

Tai, C. (2018). Why South Koreans are trapped in a lifetime of study. [online] South China Morning Post. Available at: https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/society/article/2173414/schools-never-out-why-south-koreans-are-trapped-lifetime-study [Accessed 24 Oct. 2019].

University & Aid (n.d.). View of university in Korea. [image] Available at: https://scholarshipsandaid.org/2017/09/08/2018-korean-government-fully-funded-scholarship-program-for-study-in-korea/ [Accessed 19 Oct. 2019].

Yang, H. and Kim, C. (2019). South Korea’s latest big export: Jobless college graduates. Reuters. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-jobs-kmove-insight/south-koreas-latest-big-export-jobless-college-graduates-idUSKCN1SI0QE [Accessed 25 Oct. 2019].