Band-Aids can’t fix this problem

We’ve all seen them, bought them and worn them. Band-Aids have always been a part of our lives, unless you were born before 1920. Most people even know the iconic chant “I am stuck on Band-Aid brand’ cause Band-Aid is stuck on me”. Band-Aids have always come to our savings. They are iconic and a staple in every household.

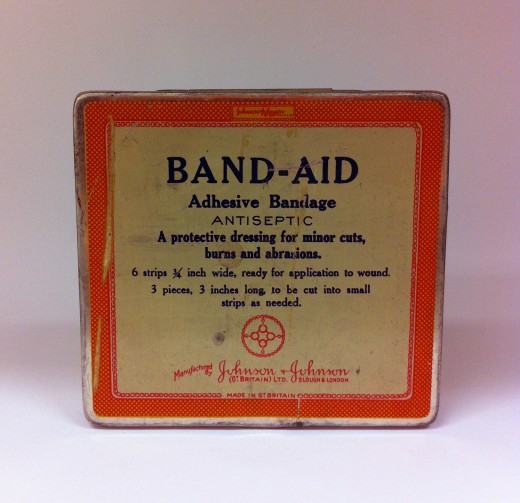

Band-Aids (fig.1) were invented by Earle Dickson in 1920, an employee at the time at Johnsons and Johnsons Co. The idea came to mind when Dickson noticed his wife struggling to constantly apply new bandages to her hands and fingers as she constantly burned herself while cooking dinner. Bandages before Band-Aid consisted of a separate gauze attached with tape. Both had to be cut and placed by an individual. Bandages never stayed tacky for long and could be removed with the slightest touch of water.

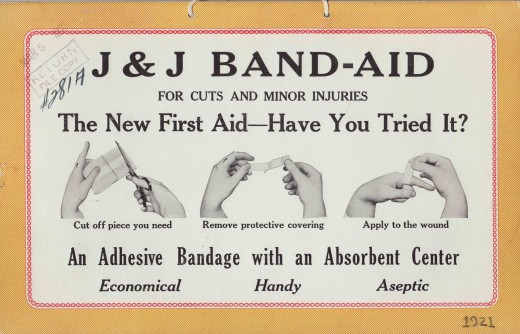

Earle decided then to reinvent bandages by creating a ready-made product, easy to apply and long wearing. By doing so, he also re-invented the process (fig.2). He invented the Band-Aid by attached a gauze the centre of a strip and sterilized it. After the approval of the first prototype by Johnson and Johnson, Band-Aids were sold all across America. Contrary to what many might think, Band-Aids didn’t sell well. So the marketing team led by Harry Webber sold them to Boy Scouts and used that as a publicity stunt. Soon Band-Aids were flying off the shelves.

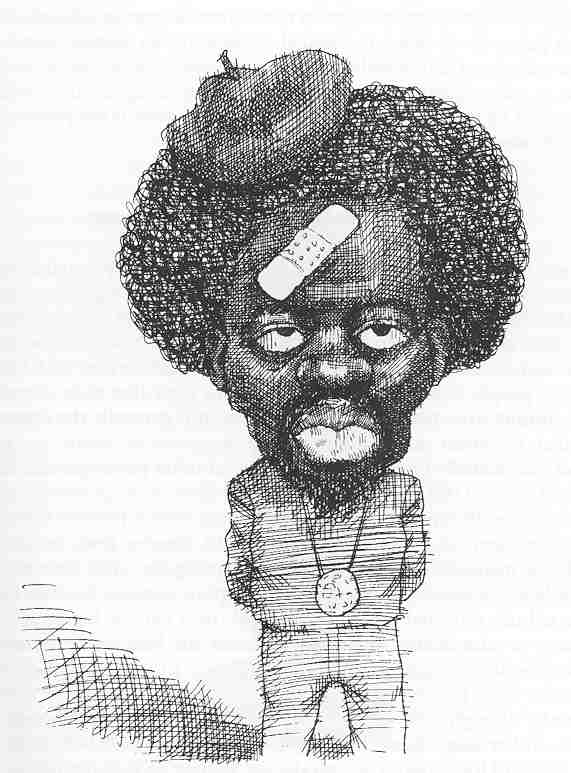

Band-Aids were sold as “Neat, Flesh-Colored, Almost Invisible” (fig.3) which polarized and discriminated people of colour. They were flesh coloured and almost invisible to only white people. This did not go unnoticed. Many began to protest Johnson and Johnson lack of inclusivity and the blunt and racist disregard for humans of skin tone other then light pink. Artist like Preston Wilcox mocked the brand.

Even with all the backlash received, Band-Aid did not change or add any other skin tone. Harry Webber described the problem as a “non-issue” due to the fact that Johnson & Johnson were directing their products to a majority demographic. To this day, with the many varieties of Band-Aids Johnson & Johnson have produced, not one was fit to cater to darker skin tones.

Work Cited

“Band-Aid.” The American Heritage Dictionary of Medicine, edited by Editors of the American Heritage Dictionaries, Houghton Mifflin, 2nd edition, 2015. Credo Reference, https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/hmmedicaldict/band_aid/0?institutionId=6884. Accessed 06 Nov. 2019.

Bellis, Mary. “History of Band-Aids: From Earle Dickson to Boy Scouts.” ThoughtCo, ThoughtCo, 2 Mar. 2019, www.thoughtco.com/history-of-the-band-aid-1991345.

Malo, Sebastien. “The Story of the Black Band-Aid.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 7 Feb. 2018, www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/06/the-story-of-the-black-band-aid/276542/.

“ Our History.” BAND-AID® Brand Adhesive Bandages – Brand Heritage, web.archive.org/web/20130615114556/http://www.band-aid.com/brand-heritage.

Images and Video

Fig.1 Margaret, et al. “BAND-AID® Brand Adhesive Bandages Tins!” Kilmer House, 19 Apr. 2013, www.kilmerhouse.com/2013/04/collect-a-piece-of-johnson-johnson-history-band-aid-brand-adhesive-bandages-tins.

Fig.2 Margaret, et al. “BAND-AID® Brand Adhesive Bandages Tins!” Kilmer House, 19 Apr. 2013, www.kilmerhouse.com/2013/04/collect-a-piece-of-johnson-johnson-history-band-aid-brand-adhesive-bandages-tins.

Fig.3 “Band-Aid Plastic Strips Commercial (1955).” YouTube, 1995, www.youtube.com/watch?v=MX8aK0ZsQHo.

Fig.4 Malo, Sebastien. “The Story of the Black Band-Aid.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 7 Feb. 2018, www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/06/the-story-of-the-black-band-aid/276542/.