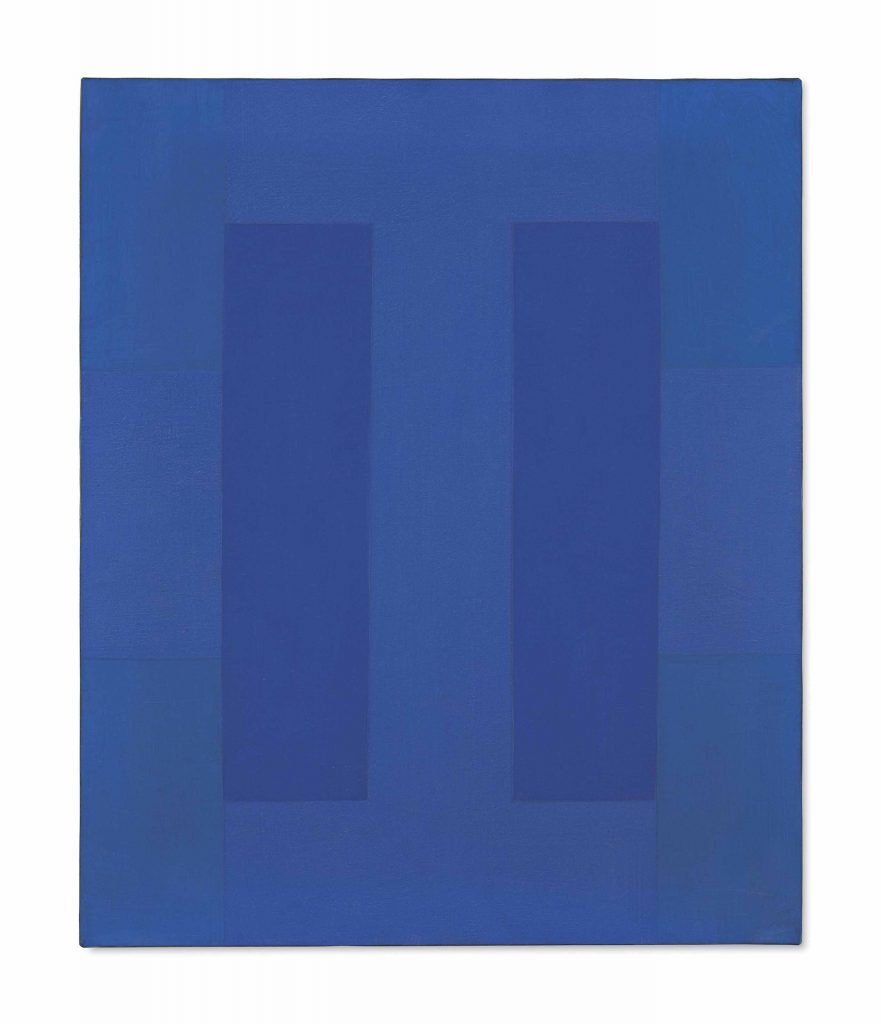

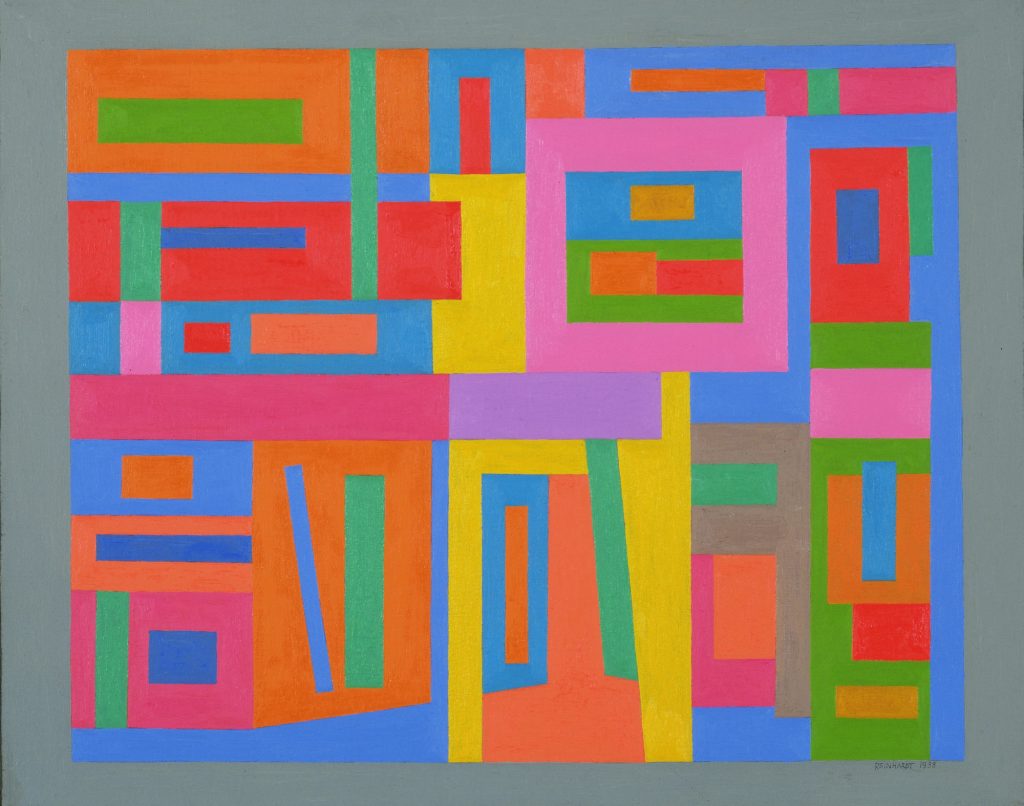

Adolph Frederick “Ad” Reinhardt, a New York-based abstract artist who lived from 1913 to 1967. He was a member of the American Abstract Artists and part of a movement that was eventually coined Abstract Expressionism. Due to his extensive work, he had a major influence on conceptual, monochromatic, and minimal art painting. Two of these types of painting, monochromatic and minimal, came about around the 1940s and 1950s respectively as his work started to gain more and more traction in the artistic community.

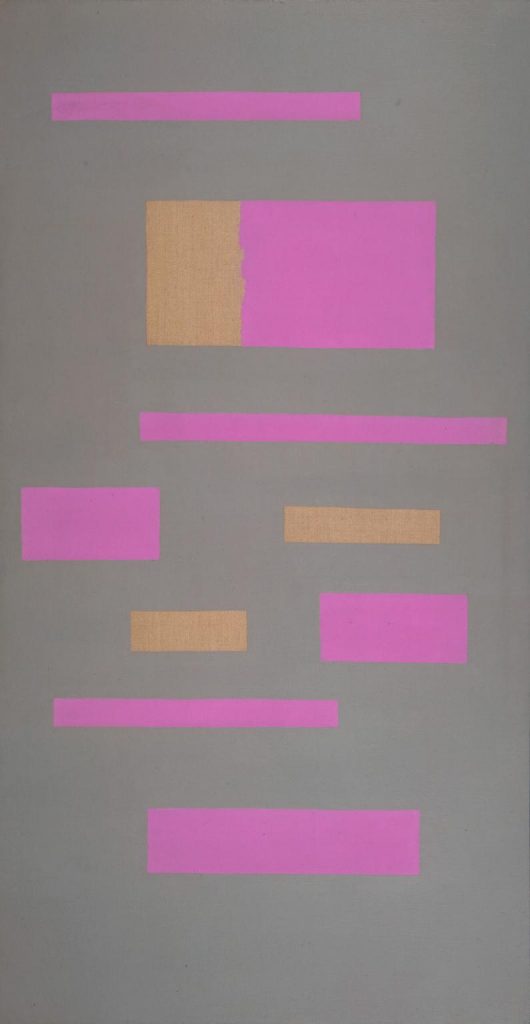

This painting is amongst his monochromatic paintings that secure their place in history. It’s part of a series of paintings called The Black Paintings. To the untrained eye, it may just look like a canvas caked in black paint, however, little did I personally know, that it is composed of many different shades of black. His reasoning is that it causes the viewer to ask if there is such thing as an absolute, even in black which most viewers don’t consider a colour.

For myself, I don’t really care for it. I’m sure there is a hidden meaning behind this and most of his work, but I just don’t see it.

Abstract Painting c.1951-2 Ad Reinhardt 1913-1967 Purchased 1972 http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T01531