This is an interest piece I decided to do because it fits into life/culture, fashion, and geopolitics but I didn’t get assigned to any of those, so I chose to do this on my own time, and maybe it’s of interest to anyone who happens on my blog.

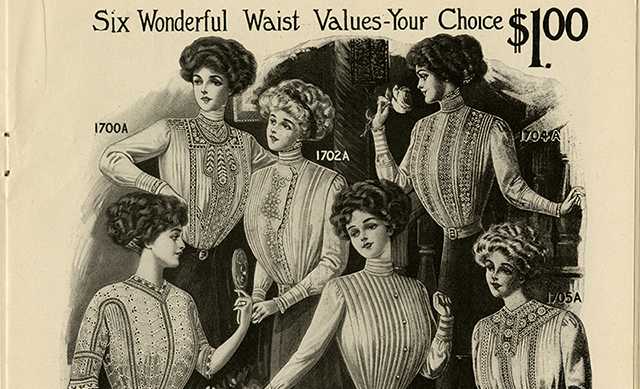

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was one of the many industrial factories in New York City. Residing in Greenwich Village, the Triangle Shirtwaist Company’s factory specialized in making Shirtwaists, which is a type of blouse that was worn by women in the 19th and 20th centuries, and could often be seen as an indication of women’s liberation, due to its allowance for freedom of movement in comparison to the restrictive nature of previous clothing items designed for women.

The factory was owned and operated by Issac Harris and Max Blanck, who were frankly, the worst. They provided employment for hundreds, but the conditions in which these people worked in were abysmal to say the least. Fabric was piled under tables and into corners, as though waiting to be lit. Workers were not permitted to smoke on the job but it was not regulated and many did anyways. There were about 500 employees crammed into the 8th, 9th and 10th floors of the Asch Building, working 52 hours a week, minimum.

Many of the staff were vastly underpaid, somewhere between $3-6/hour (adjusted for inflation). This was due to the fact that many of them were women, and migrant women at that. A good many of them had children to care for, or were children themselves, and came to New York to follow the American dream, working in the factory to survive.

On Saturday, March 25th, around 5pm, a fire started on the 8th floor. The fire alarm was only rung after a passerby from the street noticed smoke pouring out of the windows. The 8th floor employees were able to reach the 10th floor staff via telephone to warn them about the fire, but there was no way to contact the 9th floor. Yetta Lubitz, a survivor of the fire said that the fire itself was the only warning that they got, and they found out about it once it got there.

The fire is speculated to have started from a cigarette being extinguished in a pile of scrap fabric that had accumulated over two months. There were also theories by newspapers at the time that the fire was actually a case of arson, as it wasn’t uncommon for the owners of textile factories to use back door connections to burn down their own factories after their products went out of style in order to collect insurance money. Though shirtwaists were popular and the industry was competitive, it is not beyond the realm of possibility.

While there were fire exits built out to the streets on either side of the building, the exit to Greene street had been blocked by the fire, and the door to the stairway descending to Washington street had been locked. There was a padlock on the door that was only unlocked at the end of the day by the supervisor, as it was standard procedure to check women’s purses to prevent them from stealing. The man who had the key had already fled the building. This was a primary reason for the vast losses that occurred.

Many people fled to the roof, including both factory owners and their children, who happened to be visiting at the time of the fire. There was another stairway from the roof to Greene street, but it was poorly built and never maintained so when the many panicked people piled onto it, it collapsed and about 20 people fell to their deaths. Firemen arrived with ladders but they only reached the floors below the fire, people jumped from the windows into fire nets, but the only ones they had tore when three women jumped from the window at one time.

There were elevators within the building, but they could only hold so many people and were very slow. The elevator operators, Joseph Zito and Gaspar Mortillalo, saved lives by continuing to operate the elevators to help people escape instead of fleeing. One elevator buckled under the heat of the fire, and the other became inoperable due to people jumping down the elevator shaft, trying to escape.

Many people who could not reach the stairs or the elevators ended up using the last resort: the windows. Many people leapt from the 8th, 9th and 10th floor to their deaths. Bystanders gathered to witness 62 people fall to their deaths from the windows. There were accounts of a man and a woman kissing before jumping out of the 8th story window to their deaths.

Apart of the crowd gathered on the street, William Gunn Shepard, a reporter said, “I learned a new sound that day, a sound more horrible than description can picture – the thud of a speeding living body on a stone sidewalk”.

In total, 146 people died as a result of the fire. 123 of those were women, 23 were men, almost all young immigrants. Their bodies were lined up on the street in the hopes that their families would come to identify them, and only 6 were left unidentified. Historian Micheal Hirsch managed to identify all of the unnamed victims in 2011.

There was a large funeral procession through the city to mourn the tragedy of the people lost in the fire, and there is a monument of a woman kneeling at the site of the fire to commemorate the event.

Fortunately, the owners of the factory Max Blanck and Issac Harris went to trial for first and second-degree manslaughter in late 1911, due to the neglect of safety standards and fire exits within their factory. During the trial, the defendants council belittled, mocked and undermined the victims and survivors of the fire, in order to destroy their credibility and that of the prosecution. Unfortunately, the factory owners were acquitted for the manslaughter charges. They had to pay a fine due to liability for wrongful death within the workplace, which required them to pay about $75 per casualty as a result of the fire.

The insurance company deemed the losses worth $60,000 more than the declared losses, resulting in Blanck and Harris receiving about $400 per life lost in the fire. They made money off of the deaths of the 146 people that died as a result of their neglect.

The prosecution kept working, and in 1913, Max Blanck was arrested and fined, and payed the minimum fine of $20.

The primary result of this fire was a tragic legacy, as well as the formation of workers unions, better conditions for staff and safety regulations within the workplace. Between the fire in 1911 and 1913, up to 64 new bills were proposed to influence labour laws and regulations.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire still effects the world today. On the centennial of the fire there was an organized event that included public speakers, conferences and a parade, where many women carried shirtwaists like flags to mourn their fallen sisters.

References:

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/triangle-fire-what-shirtwaist/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangle_Shirtwaist_Factory_fire

https://www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/triangle-shirtwaist-fire