In the past, illnesses and ailments were unexplainable phenomena that meant you had sinned and were being punished by the gods. However, as science and philosophy began to take shape in places like ancient Greece, physicians like Hippocrates began to make new observations about illness and its affects.

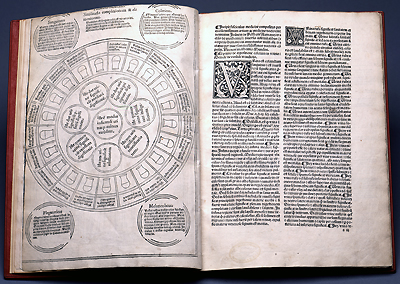

what was humorism?

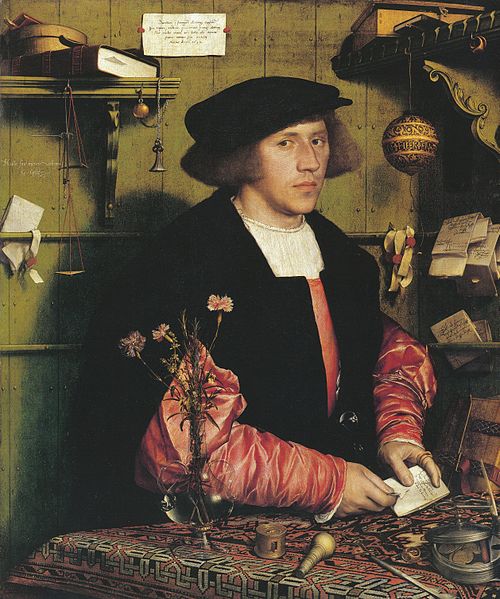

Humorism was a theory that was made by Hippocrates, a physician in ancient Greece, and was used to treat people’s illnesses by balancing the four fluids in the body. It was believed that if the four fluids– phlegm, blood, yellow bile, and black bile– needed to be kept in balance in order to keep a person healthy. The balance of the humors were affected by an individual’s gender, environment, lifestyle, mental state, and even by the planets. If someone had an excess of a fluid, then a physician would have them release the excess by urinating, letting blood and leeches, purgatives (like laxatives), or blistering the skin with hot irons. Symptoms of excess fluids included runny noses from too much phlegm and bloody noses from too much blood.

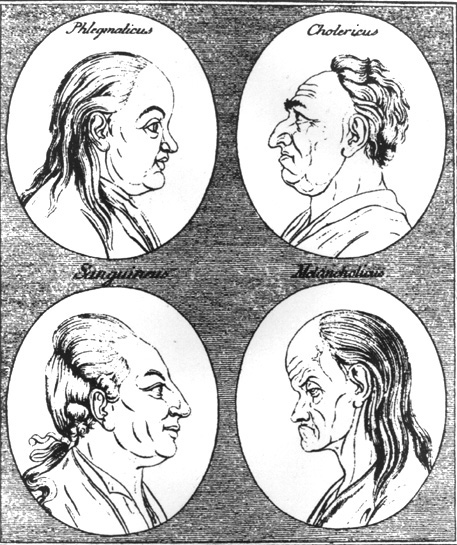

The four Temperaments

In humorism there were four temperaments called melancholic, choleric, phlegmatic, and sanguine. It was believed that every person had a natural temperament that they fell under, and that they needed to balance themselves by having the opposite temperament in their lives. For example, if a person was considered melancholic, then they needed to take purgatives to remove excess black bile in their bodies or they would need to. A person’s temperament did not stay the same and changed over time. As people aged they naturally moved from choleric to sanguine and then to phlegmatic and finally to melancholic. When seasons changed, a person had an excess of whichever temperament was associated with the season. In autumn for example, a person might have more phlegm in their body that caused their runny nose.

temperament chart:

| Temperament: | Melancholic | Choleric | Phlegmatic | Sanguine |

| Humor: | black bile | yellow bile | phlegm | blood |

| Season: | winter | summer | autumn | spring |

| Age: | old age | childhood | maturity | adolescence |

| Element: | earth | fire | water | air |

| Qualities: | cold and dry | hot and dry | cold and moist | hot and moist |

| Organ: | spleen | gall bladder | brain | heart |

| Planet: | saturn | mars | moon | jupiter |

appreciating modern medicine

Learning about the past of medicine brings me a new appreciation to our current medical knowledge and the practice of doctors that is strongly regulated. While the theory of humorism is a fascinating and important first step into identifying illness and disease in the human body, I can’t imagine having a doctor decide I have too much blood and need leeches to drink the excess from my body. Please keep the leeches away from me and my blood.

sources:

- https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/legacy-humoral-medicine/2002-07

- http://broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/techniques/humours

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zyscng8/revision/1

- http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/humoralism-1

- https://blogs.library.duke.edu/rubenstein/2016/09/15/delicate-balance-understanding-four-humors/

- https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/shakespeare/fourhumors.html