Modern History at a Modern University

WHY?

What goes through a student’s mind when they are choosing their courses for the next term? Do they ever stop to wonder how a particular course was thought into existence? How deeply do they ponder about the origins of history courses? Do students ever ask why this particular topic and why is it being taught now?

What I can determine from experience leads me to believe that not much critical thinking goes into selecting a course beyond how it fits into the degree or a student’s personal interest. However, I have decided not only to ask why and how Capilano’s history courses were created but also how the political and cultural events of the time were reflected through the course offerings and how they changed throughout the years.

My overall goal was to discern what role, if any, Cold War events played on the history curriculum at Capilano university from its opening in 1969 to 1995, four years after the official end of the Soviet Union.

HOW?

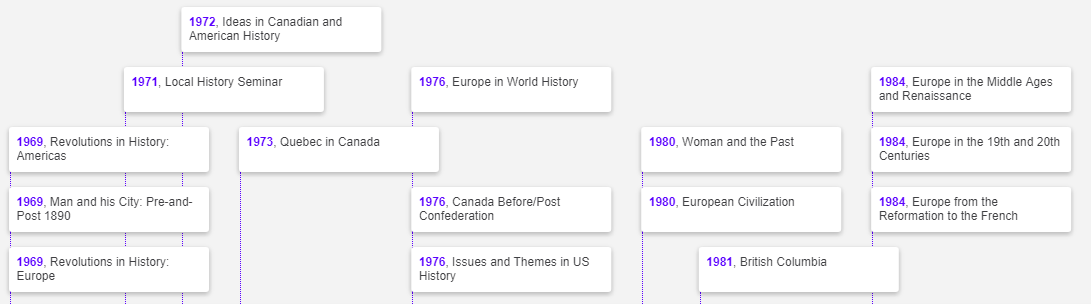

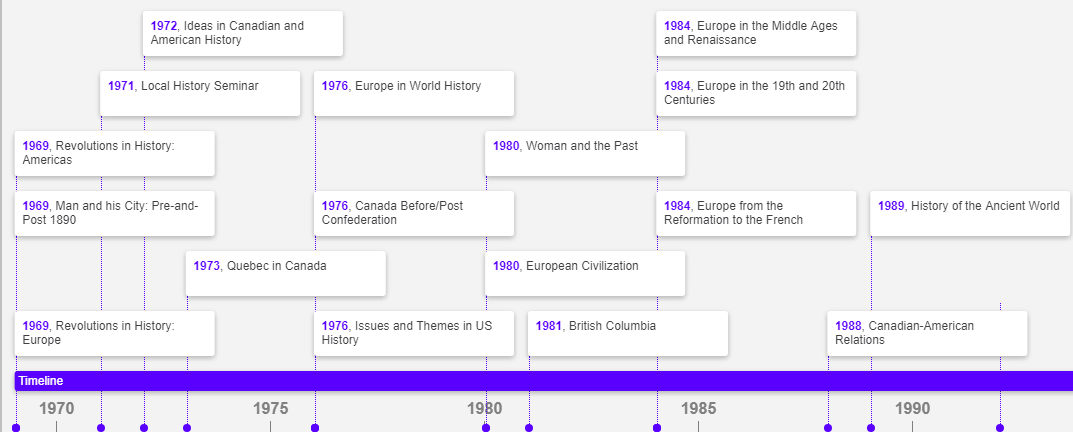

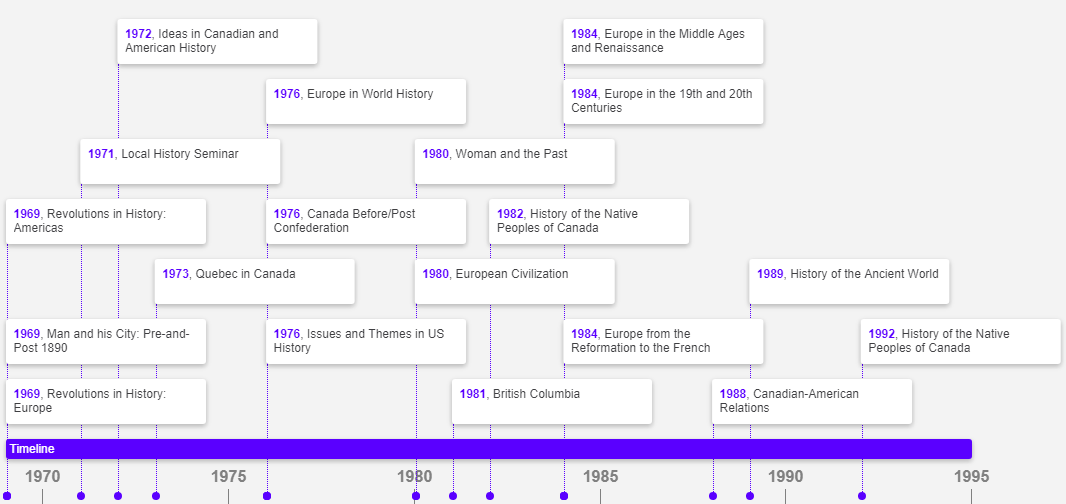

The Capilano academic calendars display a wealth of information including maps of the campus; admission guidelines and course requirements; institutional administration and more. Nevertheless, if you do not know what you are looking for when reading through them it can easily become an overwhelming experience and as the university progressed through the years, so did the amount of content on the calendars. To understand how they were displayed, I knew that I would first have to take a comprehensive survey of the calendars to tease out any patterns in the way the programs where set up and displayed throughout the years. I logged all the courses on a basic timeline so that I may view them in a context of what and when so that I may later try to understand the why.

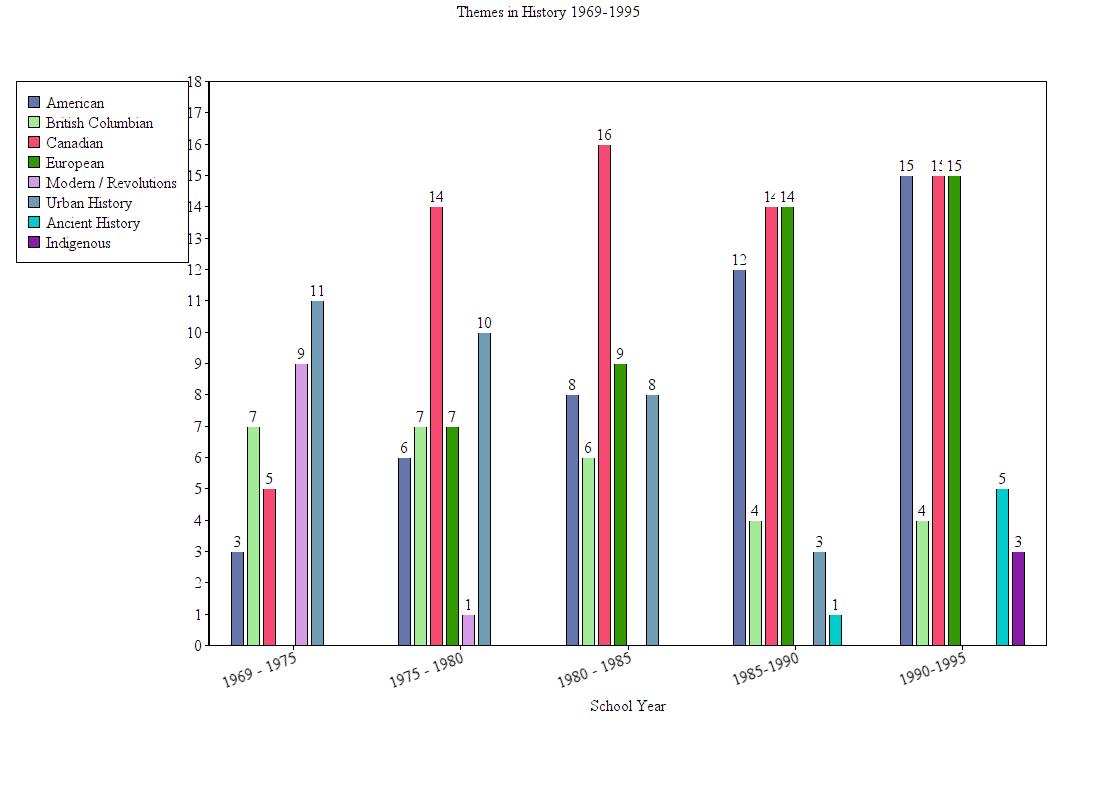

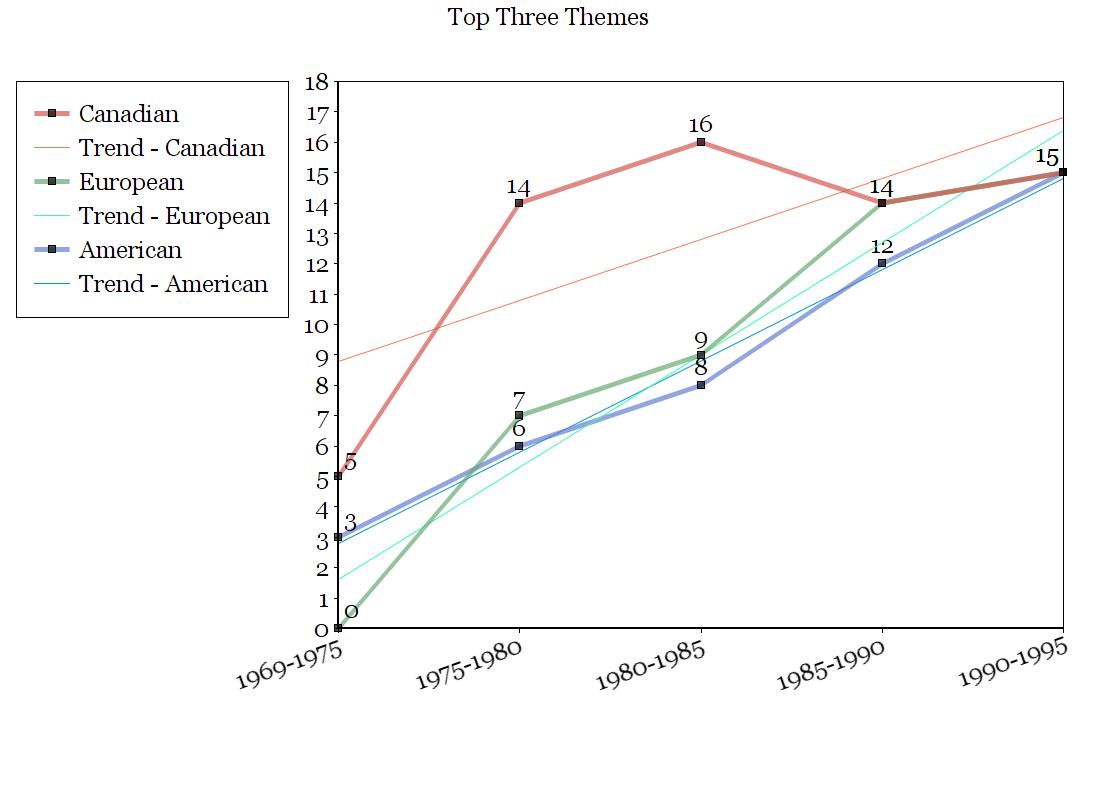

However, this wouldn’t be just quick gander through the calendars once before calling it a day and I knew that if tried to pull information from all of the calendars at once that data would be left out, lost, or perhaps overlooked. Therefore, I had to be practical in my methods of observing and recording information. I choose to separate the dates into five (in one case six) year spans: 1969-75, 1975-80, 1980-85, 1985-90 and 1990-95. This would allow me a closer reading to distinguish between the small shifts, changes, and additions to the content presented in the history program which I could later form together to get the comprehensive whole picture. From there I logged how many times a certain historical theme came up during each five-year period.

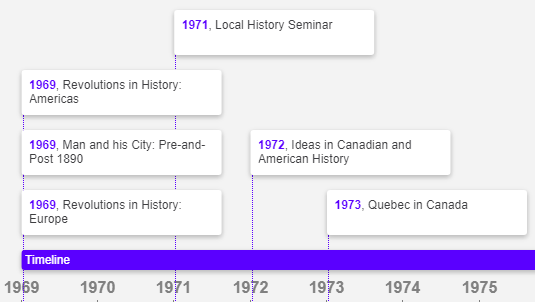

During the first six years of Capilano’s opening, the core focus in history was the origins of urban sprawl with two courses entitled ‘Man and His City’ both pre-and-post 1850. These two courses reoccurred every year until the mid eighties. The other major focus in the early years were two courses focusing on revolutions in Europe and the Americas. The former had a longer period on the curriculum, staying well into the late seventies while the latter had only a three-year span.

Canadian history, which surprisingly wasn’t featured often in the curriculum until the mid-seventies, was the most consistent and reoccurring theme throughout the following years; followed closely by American (US) and European history. By 1995, those three themes evened out in occurrence in curriculum.

British Columbia’s history was the most consistent theme offered throughout the years. It began with a course entitled ‘Local History Seminar’ in 1969 which focused on the North Shore and surrounding areas, until 1981 where it was replaced by a broader course on all of British Columbia.

1969-1975

Coincidentally, the beginning of the classes at Capilano College aligned with the Cold War Détente between America and the Soviet Union in 1969. The first history 100 course to be offered at Capilano was “Revolutionary Ideas in History: The Americas”. Despite the title inferring that the course content would discuss the multiple revolutions and movements that swept through Central and South America during previous years, the course description states that the course is “an analysis of the major ideas which have influenced the social, economic and political developments of Canada and the United States.” Unfortunately, there is no further information available that would help us better understand how and what this course taught. We can include in our account the fervor of anti-communism at Universities in the US at the time and draw our own conclusions as to why the entire continent of South America would have been left out.

The course entitled ‘Revolutionary Ideas in History: Europe’ describes its content to regard “capitalism, communism, fascism and socialism [with an ] emphasis…on these ideologies in action.” Obviously, they found it important to teach students the varied ideals as a concept but the focus seems to be rather ambiguous. How far back did they reach to? The French revolution? The events that lead to the Second World War? Would they have discussed Lenin and Stalin, and if so, in what context? How did the professor teach it? Did they approach it as unbiased history students or as residents at a Western university? Without looking at a full course outline, we are left only with questions and speculations.

Dr. Robert Campbell, former history teacher at Capilano University from 1978 until he became Dean of the Arts and Sciences department in 2008, shared with his insights into why history classes are chosen by stating that “historians are very much influenced by the times in which they live.” Whether that includes issues that are currently occurring; trends that are re-emerging; or new historic discoveries is up for us to distinguish. Dr. Campbell eludes to this by stating that “when something becomes a contemporary social issue, a historian will often put on his or her hat and say, ‘I wonder where that came from?’”

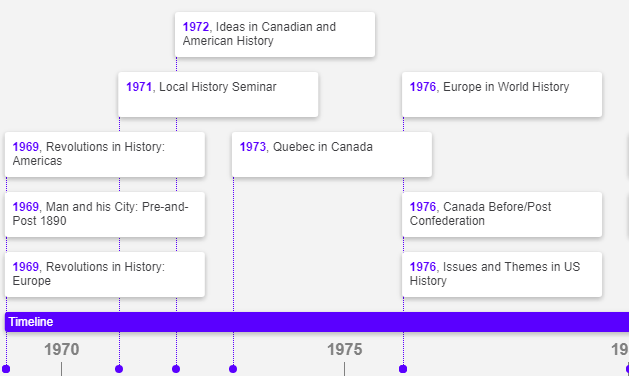

1975 – 1980

In 1976, the focus on Canadian history became more comprehensive, splintering from a course entitled ‘Ideas in American and Canadian History’ into two well developed courses on pre and post confederation history in Canada. Both first year courses offered students what would likely be their first real glance at an interesting Canadian history outside of high school. Former Capilano history teacher H. Towser Jones believes that high schools teach Canadian history in a way that discourages students from furthering their education when they reach university. While this could provide insight on trends, it wasn’t only disinterest in students that caused the discrepancy in courses. Jones states that “as Canadian history become less and less a requirement for further degrees or opportunities, than the demand for Canadian history reduced.” Her statement focuses on the decline that started in the late nineties, however, what she is saying is relevent and applicable. For any course to exist, there must be demand for it.

In the sixties a movement swept through Quebec pushing for its own sovereignty. Parti Québécois were established, and in 1976 they won 71 seats in parliament. Independence was discussed within the populace but ultimately rejected by the majority and that goal was put on the back burner. However, Canadians became interested in the francophone province and therefor a course entitled ‘Quebec in Canada’ was a fixture in the history curriculum from 1973 onward.

1980-1985

In 1978, Dr. Robert Campbell started teaching at Capilano and with him he brought his expertise in American and Canadian history and the curriculum became further streamlined. The ‘Local History Seminar’ was done away with and a more comprehensive ‘British Columbia’ history was formed. In total, four history courses with Canadian issues as the main topic were offered to students, followed by American history and European history. The latter which began to be more frequent in the curriculum since the mid-seventies, and just like Canadian history became more disciplined as time went on. Instead of a largely broad topic labeled “Europe in World History”, the courses became more focused and time specific.

In 1980, “Woman and the Past” was offered to students which discussed “women’s participation in and contribution to the making of history.” After the civil rights movements of the 1960’s, academic work from a feminist perspective re-emerged and Woman’s Studies programs and courses in Universities started to be a prominent field in academia. History in particular was often filled with men who did impressive deeds (with the rare exception of queens and martyrs) leaving women’s role in the formation of the world to be largely neglected. The entry of a history course focused entirely on woman was undoubtedly welcome.

1985-1990

When I asked Dr. Campbell why there seemed to be a shift to American and Canadian politics in the curriculum from broader topics, his answer was that it was partly because of him having come to Capilano with a master’s degree from UBC and expertise regarding history in United States and America. The ‘British Columbia’ history course and ‘Canadian-American Relations’ course were both developed by Dr. Campbell himself. He states that students were keen on the BC course as “they could identify with it as it brought history close to home.” Towser Jones expands on this further by saying that “in the late eighties local history as discipline was becoming very popular [because] technology was changing, ways at looking at things were changing, the ability to look at the individuals in the street was becoming available to us.”

By the late eighties, it was clear that the arms race was waning and with it the power of the Soviet Union, and by 1989 the Warsaw Pact officially started to dismantle with the collapse Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany. Interest shifted as the constant tension of the Cold War changed to issues closer to home. One of the few courses that was still present up until the late eighties and the early nineties was entitled ‘The City’, which had developed from ‘Man and the City’. The two-part course discussed the formation of the European city and a “comparison of urban developments” in Canada and America. In fact, a large portion of history courses had references between Canadian culture in comparison to America. Dr. Campbell states that this is because in “Canada there is a constant of the United States and in the United States there is the constant presence of Canada regarding the world of history.”

1990-1995

The Soviet Union was officially dissolved at the end of 1991 and so the supposed communist threat was eliminated. At Capilano, “The City” had finally been removed from the curriculum, and Ancient History replaced it as the core history 100 course. Overall the content had become wholly streamlined as well as complimentary with other courses so that history students would get a more comprehensive and linear learning.

Towser Jones started at Capilano in 1989 when the demand grew for European History courses. She brought with her expertise in Europeanism and passion for Ancient History where she says turned “dry historical names, dates and places into real people doing their very best in real times.” This was especially relevant to the time where modern history was at a more peaceful standstill than in had been in a long period of time and an interest in a distant history was starting to develop as more than just a sarcophagus in a museum.

First Nations history was the final course created in 1993 as interest in the indigenous peoples in the Canada began to grow. Dr. Campbell admitted that it became increasingly easier to teach first nations history to students as interest in it grew, and expanded out of the dry knowledge learned in high school regarding the fur trade. Considering that the school was named after a Joe Capilano, chief of the Squamish nation in the late ninetieth to early twentieth century and the Capilano buildings lie on their unceded traditional land, it could be viewed as a start to learning about the original peoples of Canada or rather late in coming.

Final Thoughts

When examining the Capilano history curriculum from the first thirty-six years, we must take a few things into account. We must first note that the school is new in comparison to similar schools in BC and Canada, and developing the curriculum for a new institution would be different and more difficult than one well established. Courses offered grew from just four to twelve well rounded selections by the end of 1995 as both demand and experience grew. Secondly, demand itself is the second to note and when it comes to comparing history courses to recent history, regardless if a large event happened or not, the course content must be of interest to students for the professors to teach it. Finally, the teacher at the University is the final and largest impact on courses offered. If a teacher’s expertise lay in the European Renaissance they are not going to be the right fit to teach history regarding the world wars and vise versa. They teach what they know, and adjust it to the demand at the time. Dr. Robert Campbell explains this all rather poetically by saying that “curriculum development in general is a response to our perceptions of what students want or need, our own expertise and also, what people in other institutions as well.”

Words Cited

Campbell, Dr. Robert. Personal Interview. 30 November 2017

Capilano Calendars. “1969-1970 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1970-1971 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1971-1972 Calendar”. LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars.”1972-1973 Calendar”. LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1973-1974 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1974-1975 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1975-1976 Calendar”. LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1976-1977 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1977-1978 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1978-1979 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1979-1980 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1980-1981 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1981-1982 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1982-1983 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1983-1984 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1984-1985 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1985-1986 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1986-1987 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1987-1988 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1988-1989 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1989-1990 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1990-1991 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1991-1992 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1992-1993 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1993-1994 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Capilano Calendars. “1994-1995 Calendar.” LBST 200 Primary Resource Project. Capilano University, North Vancouver. Accessed via Moodle.

Jones, H. Toswer. Personal Interview. 30 November 2017