Artefact Spread Rationale

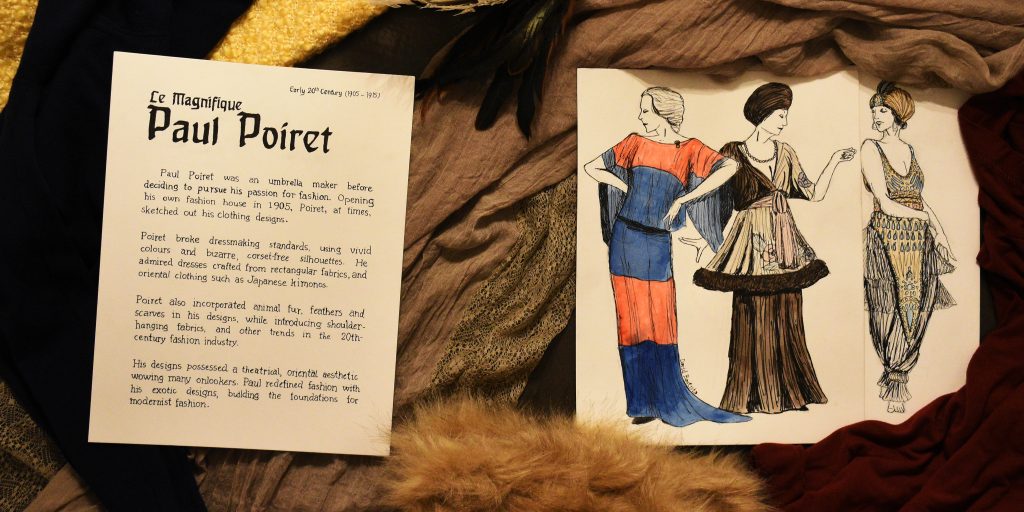

I was assigned to design a fashion artefact spread for Week 7, as such I wanted to cover fashion designer Paul Poiret, whose avant-garde designs inspired me to draw some of his apparent sketches in his style.

Many decisions were made, of course, before creating the final spread. For one, a wash of watercolour was added to the sketches, despite Poiret’s sketches not being coloured, to depict some of the vibrant colours that Poiret used in his clothing designs.

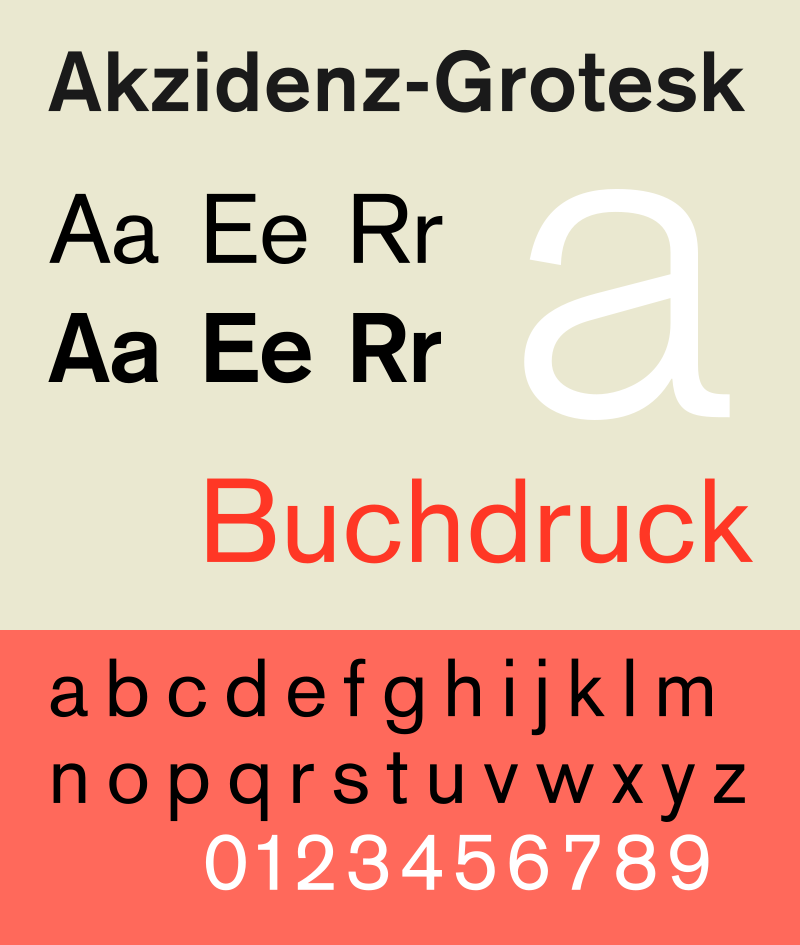

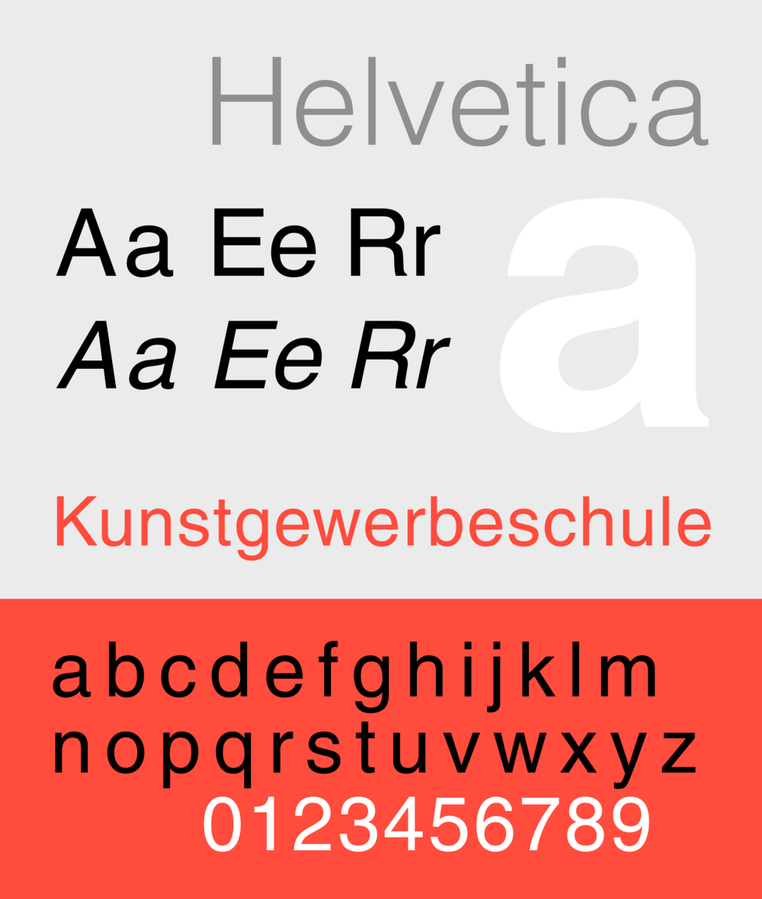

The typefaces replicated on the left side of the spread are supposed to Behrens-Schrift and Souvenir, these typefaces were chosen because they originated from the 20th century and thus matching the time period.

For the surrounding ‘objects’, the clump of feathers and fur were placed onto the spread as Poiret simply used feathers and fur trims in some of his designs. The fabrics in the back were carefully chosen depending on their likeliness to fabrics Paul himself would’ve used.

As for the orientation of the papers, the spine of the upcoming history book was considered, hence the slightly upright positioning. They were tilted slightly to make the spread more dynamic and less stiff.

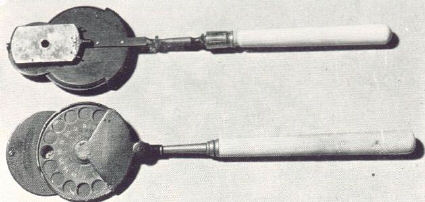

Originally, 20th-century sewing objects were to be included in the spread, however finding or crafting a pin cushion, tape measure and fabric scissors was and would have been difficult for me. It would have also caused the spread to become a bit too busy. Thus it was decided to scrap the idea of including those objects.

Considering the end result, I am satisfied. However, I do recall committing some minor mistakes with the text and sketches. The execution of the body text could have been done more carefully. As such, I give myself an 8.5/10.

Total hours spent: 19h:22m

- Research = 7:09

- Ideation = 1:58

- Execution = 8:55

- Reflection = 2:00

Research – Survey 7

Le Magnifique Paul Poiret

For Week 7, we covered Cubism and Corporate Identity within the period of 1905 to 1915. It was interesting to learn about Peter Behrens and his contributions to visual identity, typography and architectural design. I was also assigned to create an artefact related to fashion during the week, and I eventually decided to research about the French fashion designer, Paul Poiret.

Born on April 20, 1879, in Paris France, Paul Poiret was the son of a cloth maker and, as a teen, became an apprentice umbrella maker. However, Poiret’s interests lay in fashion and thus he began to work for fashion designers including Jaques Doucet.

In 1905, Paul established his own ‘maison de couture’, or fashion house in English, and was assisted by Jaques Doucet who managed to contact famous French actress Gabrielle Rejane to model for Poiret.

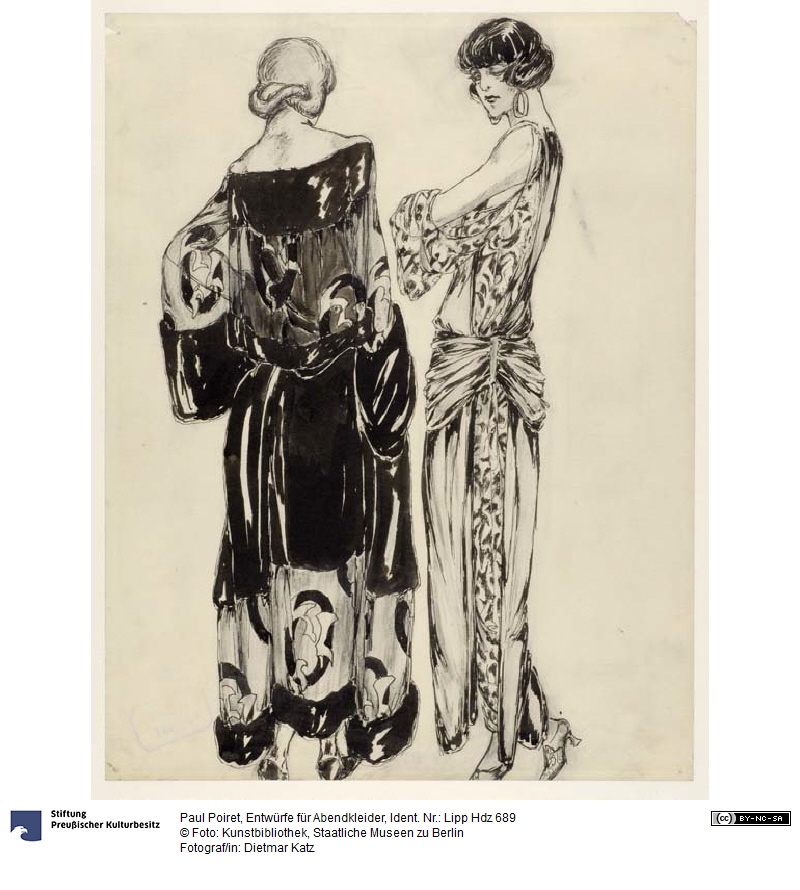

Paul was free to create his own fashion designs, influenced by oriental, eastern fashion, he introduced the Kimono shape to Europe and also made use of turbans and harem pants. Poiret’s designs took a theatrical aesthetic with fringed, draped fabrics, feathers in vibrant colours and fur trims.

He would eventually tour Europe in 1912 with a group of models, showcasing his rather avant-garde designs, and later toured the US in 1913.

The following year, he joined the war efforts in WWI as a military tailor, and was forced to close his fashion business and, afterwards, couldn’t regain his position in the fashion industry, as postwar fashions were more modernist than his exotic fashions. Poiret lost his fame and later died in poverty on April 30, 1944.

However, were it not for Paul Poiret and his bizarre fashions, modern-era fashion wouldn’t have destroyed his career, for his tendency to go above and beyond built the foundations for modernist fashion.

WORKS CITED

- “Poiret, Paul.” Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Britannica Digital Learning, 2017. Credo Reference, https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/content/entry/ebconcise/poiret_paul/0. Accessed 04 Nov. 2019.

- “Poiret, Paul.” World of Art: The Thames & Hudson Dictionary of Fashion and Fashion Designers, Georgina O’Hara Callan, Thames & Hudson, 2nd edition, 2008. Credo Reference, https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/content/entry/thfashion/poiret_paul/0. Accessed 04 Nov. 2019.

- Koda, Harold, and Andrew Bolton. “Paul Poiret (1879–1944).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/poir/hd_poir.htm (September 2008)

- Koda, Harold, and Andrew Bolton. “Paul Poiret (1879-1944).” Metmuseum.org, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Sept. 2008, www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/poir/hd_poir.htm.

IMAGES OBTAINED FROM

- https://agnautacouture.com/2014/04/06/paul-poiret-le-magnifique-part-2/

- http://www.smb-digital.de/eMuseumPlus?service=direct/1/ResultLightboxView/result.t1.collection_lightbox.$TspTitleImageLink.link&sp=10&sp=Scollection&sp=SfieldValue&sp=0&sp=0&sp=3&sp=Slightbox_3x4&sp=12&sp=Sdetail&sp=0&sp=F&sp=T&sp=19

- https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1983.8a,b/