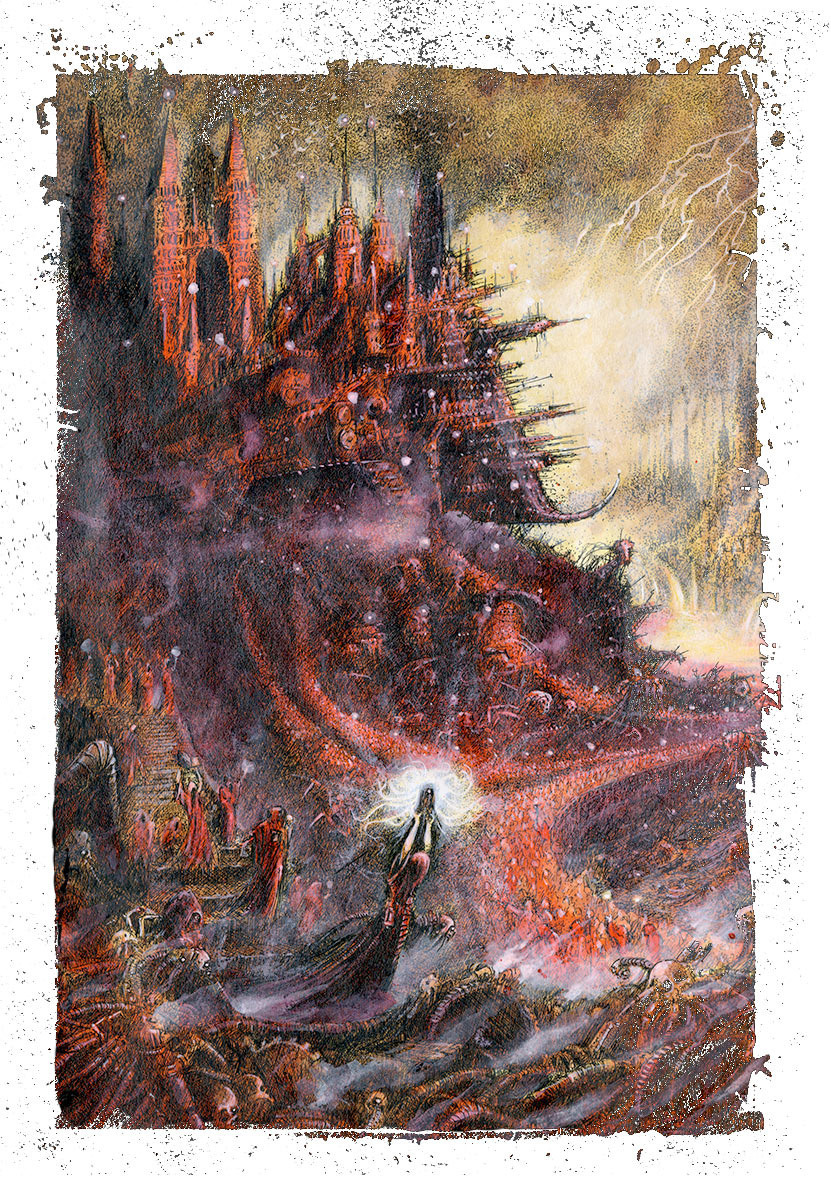

John Blanche occupies an interesting position in the ranks of illustrators that had influence on me while growing up. When I think back, his drawings (perhaps more than any other) captivated me when I was young. I had seen nothing like them before; this wasn’t the optimistic, high science fiction of Star Trek, Lost in Space and Star Wars. This was terrifying in comparison, grotesque and savage, incredibly bleak. So like any child who enjoys a good scare, I’d turn off the lights and pore over the drawings in the dark with a flashlight, losing myself in this twisting Baroque future that flowed from Blanche’s pen and brush.

Blanche’s reputation was built on the early work he did illustrating worlds for Games Workshop in the 80s. Character art, environmental and narrative illustrations for the worlds they were creating were entirely up to him at the time, they had no other artist contributing. It was a small company trading in games systems and models, publishing from the garages of the small group of friends who were passionate about building their hobby into a growing community and business. Similar to TSR, the company created by Gary Gygax to publish his Advanced Dungeons and Dragons system, Games Workshop (then known as White Dwarf) depended on a strong base of worldbuilding to capture the imagination of their audiences to bring them in to playing their tabletop systems. Blanche became instrumental in this, laying the foundation for the aesthetic that would carry their game Rogue Trader into its formative years.

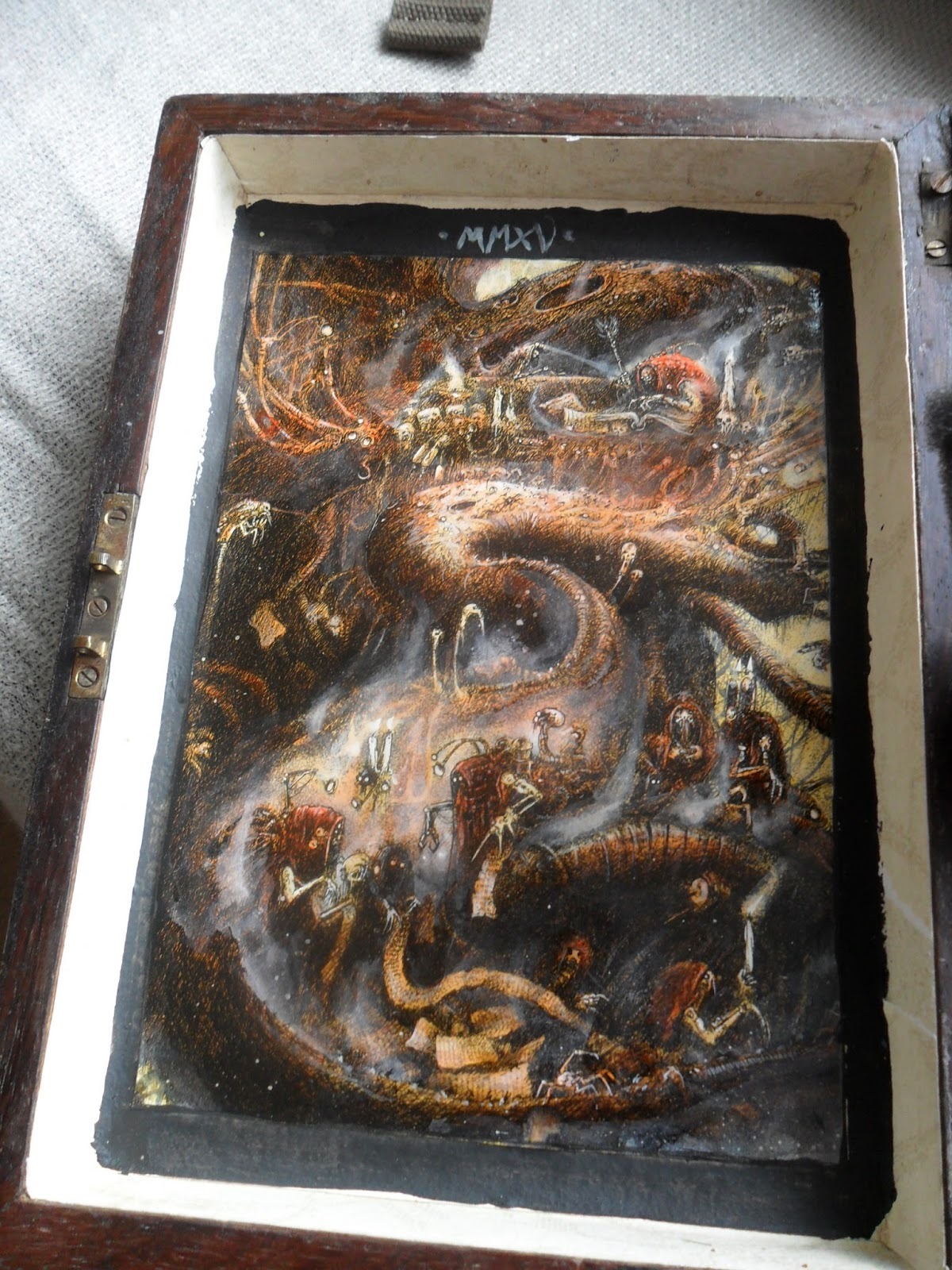

What draws me towards these works is that it reflects a period in illustration that I feel very fondly about. It was a time before concept art was taken over by digital art, before the majority of it became studio-based work. His work sometimes swings between gorgeous and naive or outright crude at points, somewhat like the work of William Blake before him. What was important was to communicate the idea, the emotion above a perfect rendering, and in this I believe he often succeeded.

There’s a certain charm in niche work from the 80s and 90s where the concept artists weren’t illustrators requiring degrees and perfected academic drawing skillsets: many were friends of friends with strong vision and drive. There’s a quality about that has a certain charm to it. Regardless of their skill level, they still created works that have turned into beloved worlds or franchises, much like Chris Metzen of Blizzard Entertainment fame.

His work drips with the punk ethos that was a driving force in so many underground subcultures of the time, walking a parallel path with things like tape trading circles in heavy metal culture and early hardcore zine culture. I work on a quarterly self-published zine called Umbra with a friend, and that DIY culture that John Blanche was a part of is something that sparks a fond feeling of nostalgia in me, and is something I love about his work and that I’d also like to tap into in my own endeavours.

Nowadays, the humble beginnings of White Dwarf have turned into a multi million dollar international company, but the work he put into creating the worlds these games take place in are universally revered within the community. To this day, he retains a legendary position in the mythology of the universes he illuminated. In his time illustrating these worlds, he created a vision that was wholly unique for the genre and he leaves a mark that lasts in the community to this day, perhaps proving that there is a niche for almost any of us if you have the vision and will to fight for it.

Sources and Images

http://convertorum.blogspot.com/p/blanche-gallery.html

Leave a Reply