The Evolution of The Chinese Writing System

Today in our Survey Design class, we covered the history of handprints and handwriting. We briefly discussed the history of handwriting in Asia, and it was interesting to learn that inscriptions were found on bones. This drove me to further research about these inscriptions, and the history of the Chinese writing system.

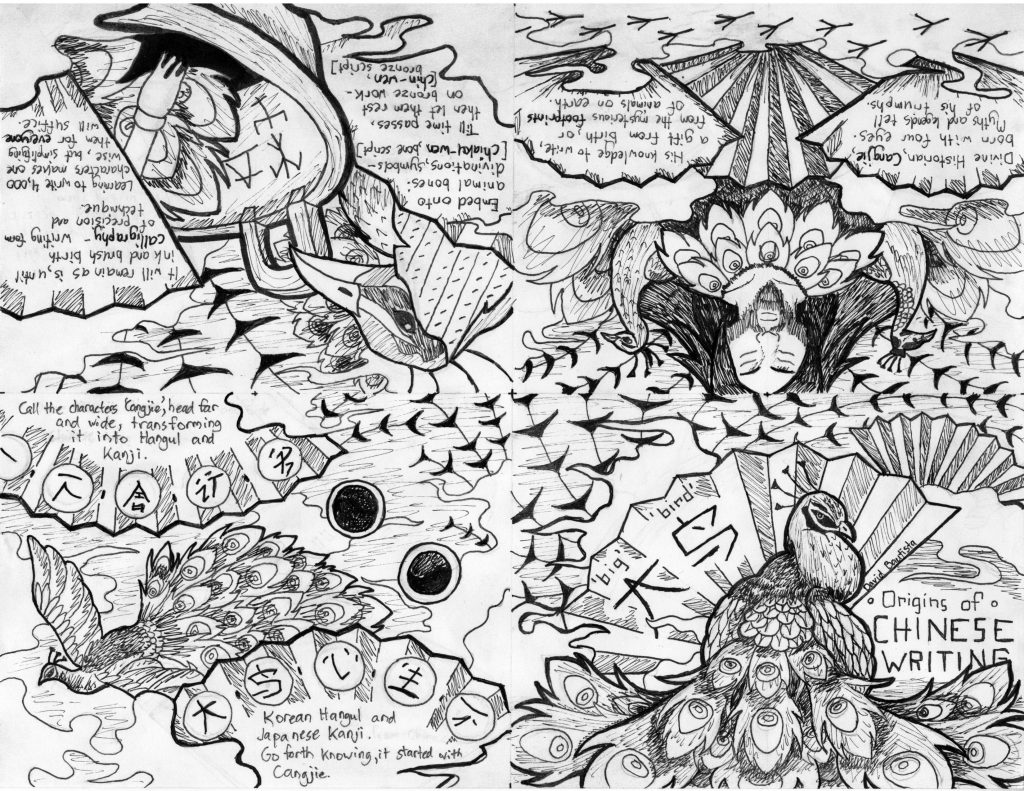

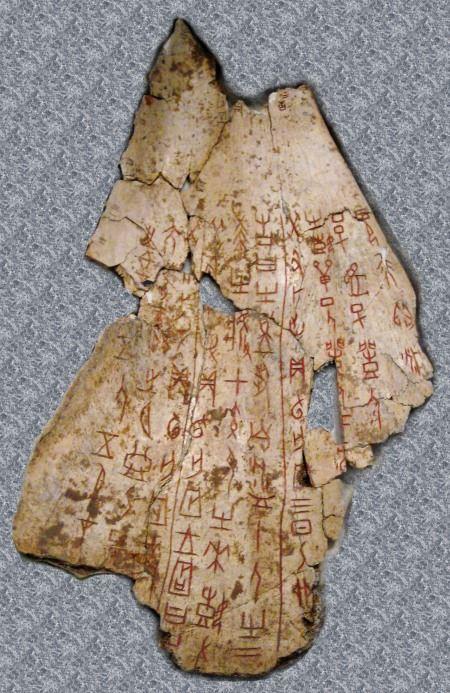

Chinese writing consists of symbols or characters ,and the earliest confirmed iteration of these characters took place sometime between the Neolithic period and half of the Shang Dynasty (around 1200 to 1050 B.C.E.). First manifesting during the reign of King Wu Ding around 1200 B.C.E., they came in the form of oracle bone inscriptions.

The inscriptions on these bones are known as chiaku-wen, or bone-and-shell script, and were commonly used in divination and were inscribed on animal shoulder blades and turtle shells. They usually depicted questions from diviners regarding subjects such as weather and luck. They were then heated, and the cracks produced by the heating determined a yes or no answer from gods or ancestors.

Samples of these oracle bones show that the characters were written in columns. The symbols themselves were more like pictograms compared to their modern-day counterparts. These are the earliest evidence of ideograms, a term referring to picture symbols often associated with the Chinese writing system.

Chiaku-wen would eventually evolve into chin-wen (or bronze script). This involved the embedding of inscriptions onto various cast-bronze objects. Similar to the writings on oracle bones, bronze inscriptions depicted messages from gods and ancestors. However, these inscriptions were permanent, making bronze script ideal for treaties, contracts and other important documents.

Chin-wen would eventually evolve into an art form known as calligraphy. Starting sometime during the 4th century B.C.E, the practice, involving ink and brush, had very strict rules in terms of its execution. These included how much ink was used and the composition of written characters.

Individual brush strokes in ideograms are known as radicals, allowing each character to be classified. All the characters fit into an imaginary, rectangular box and are known as logograms, which are symbols representing individual words. Eventually, this formed a vast library of written characters that needed to be learnt, and those who managed to learn them were considered to be wise.

Initially, different styles of calligraphy were utilized throughout China, until the reign of Emperor Shih Huang Ti (around 259 to 210 B.C.E.), who unified all of the existing writing styles. This style remained until Li Ssu, a prime minister from 280 to 208 B.C.E., developed a new style of calligraphy called hsiao chuan or “small-seal”. The result was a more abstract and graceful style, also neatly balanced in terms of form.

I will not be covering anything that occurred during the common era, since the post would be lengthened. Thus, I will be taking my leave.

Thanks, and until then!

WORKS CITED

- “Chinese.” The Columbia Encyclopedia, Paul Lagasse, and Columbia University, Columbia University Press, 8th edition, 2018. Credo Reference, https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/columency/chinese/0?institutionId=6884. Accessed 16 Sep. 2019.

- Chinese writing system. (2017). In Encyclopaedia Britannica, Britannica concise encyclopedia. Chicago, IL: Britannica Digital Learning. Retrieved from https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/ebconcise/chinese_writing_system/0?institutionId=6884

- SAUSSY, H. “Ideogram.” The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, edited by Roland Green, et al., Princeton University Press, 4th edition, 2012. Credo Reference, https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/prpoetry/ideogram/0?institutionId=6884. Accessed 16 Sep. 2019.

- “calligraphy.” The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide, edited by Helicon, 2018. Credo Reference, https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/heliconhe/calligraphy/0?institutionId=6884. Accessed 16 Sep. 2019.

- “oracle bones.” The Columbia Encyclopedia, Paul Lagasse, and Columbia University, Columbia University Press, 8th edition, 2018. Credo Reference, https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/columency/oracle_bones/0?institutionId=6884. Accessed 16 Sep. 2019.

- Writing and Literacy in Early China : Studies from the Columbia Early China Seminar, edited by Feng Li, and David Prager Branner, University of Washington Press, 2011. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/lib/capilano-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3444463.

- “typography.” The Columbia Encyclopedia, Paul Lagasse, and Columbia University, Columbia University Press, 8th edition, 2018. Credo Reference, https://ezproxy.capilanou.ca/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/topic/typography?institutionId=6884. Accessed 16 Sep. 2019.

- Yee, Chiang. “Chinese Calligraphy.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 17 Jan. 2019, www.britannica.com/art/Chinese-calligraphy.

- Asia for Educators. “Timeline of Chinese History and Dynasties: Asia for Educators: Columbia University.” Timeline of Chinese History and Dynasties | Asia for Educators | Columbia University, Columbia University, 2009, afe.easia.columbia.edu/timelines/china_timeline.htm.

- “Chapter 3: The Asian Contribution.” Meggs’ History of Graphic Design, by Philip B. Meggs and Alston W. Purvis, 5th ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2012, pp. 34–36.