Vision with Herman von Helmholtz

For Week 7 of Survey Design, we went over the years 1850 – 1895, while also covering The Great Exhibition. As this event happened in Vancouver in 1986, I do hope it returns in the future so I can experience it and travel the world without wandering too far from home.

I was also assigned to a group as a researcher, and in a general agreement, decided to cover optics during the 19th century, specifically anything related to vision. It was a bit difficult to research this topic during this period, but luckily I did find something interesting to cover for this post.

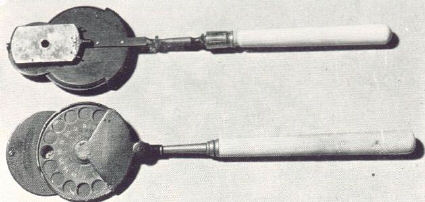

As such, I would like to introduce to you, the man responsible for boosting the development of visual optics: Hermann von Helmholtz, or Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand Helmholtz, who contributed to the study of optics, and also invented some tools that optometrists use today, with the most significant being the ophthalmoscope.

Ophthalmoscopes are used today to examine blood cells in the retina and can indicate signs of medical issues in the eye and even in the circulatory system. It also allows for the accurate prescription of eyeglasses.

Helmholtz invented the first proper ophthalmoscope in the 19th century, in the year 1851. An English inventor named Charles Babbage made a similar instrument to the ophthalmoscope earlier in 1847, but it failed to be of any use to eye doctors at the time.

Helmholtz was greatly successful due to his studies while conducting research on the eye, he found out that a clear image of eye tissue can be produced if a light is focused onto the tissue.

Helmholtz also wrote the ‘Treatise of Physiological Optics’ (c.a. 1856), where he reports on his research regarding the behaviour and characteristics of the eye, with a dose of philosophy.

The text demonstrated the eyes’ perception of distance and developed the theory of space, while also elaborating on colour vision, in response to a theory made by Thomas Young (1802).

According to Young, three primary-colour receptors worked in unison to produce the colour range an average human witnesses.

Helmholtz expands on this, stating that three types of light receptors in the eye were colour-sensitive, reacting to blue-violet, green or red light.

Within these receptors are various chemicals with different sensitivities and reactions to light, stimulating neurons and sending signals to the brain.

Helmholtz applied this expanded theory to topics such as afterimages and blindness.

Helmholtz also delves into deep thinking with the following question: if eyes do react in a form of optical phenomena, can we be sure and trust our general senses to relay information of the outside world to our brain? This was a question that Helmholtz explored and often failed to answer.

Thanks to the efforts and materialized research of Hermann von Helmholtz, humans managed to develop the understanding of eye vision that we know and follow today.

Our optometrists may have been unable to care for the conditions of our eyes, were it not for Helmholtz’s invention.

WORKS CITED

- Williams, L. Pearce. “Hermann von Helmholtz.” Biographies, 4 Sept. 2019. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hermann-von-Helmholtz. Accessed 22 Oct. 2019.

- Street, Warren R, and Philip Tolin. “Helmholtz, Hermann von.” Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, L. Nadel, Wiley, 1st edition, 2005. Credo Reference, https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/content/entry/wileycs/helmholtz_hermann_von/0. Accessed 22 Oct. 2019.

- “Helmholtz, Hermann (Ludwig Ferdinand) von (1821 – 1894).” The Cambridge Dictionary of Scientists, edited by David Millar, Cambridge University Press, 2nd edition, 2002. Credo Reference, https://search-credoreference-com.ezproxy.capilanou.ca/content/entry/dicscientist/helmholtz_hermann_ludwig_ferdinand_von_1821_1894/0. Accessed 23 Oct. 2019.

IMAGES OBTAINED FROM

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hermann-von-Helmholtz

- http://www.mrcophth.com/Historyofophthalmology/ophthalmoscope.html

- https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B0006AJDBQ/?tag=prabook0b-20