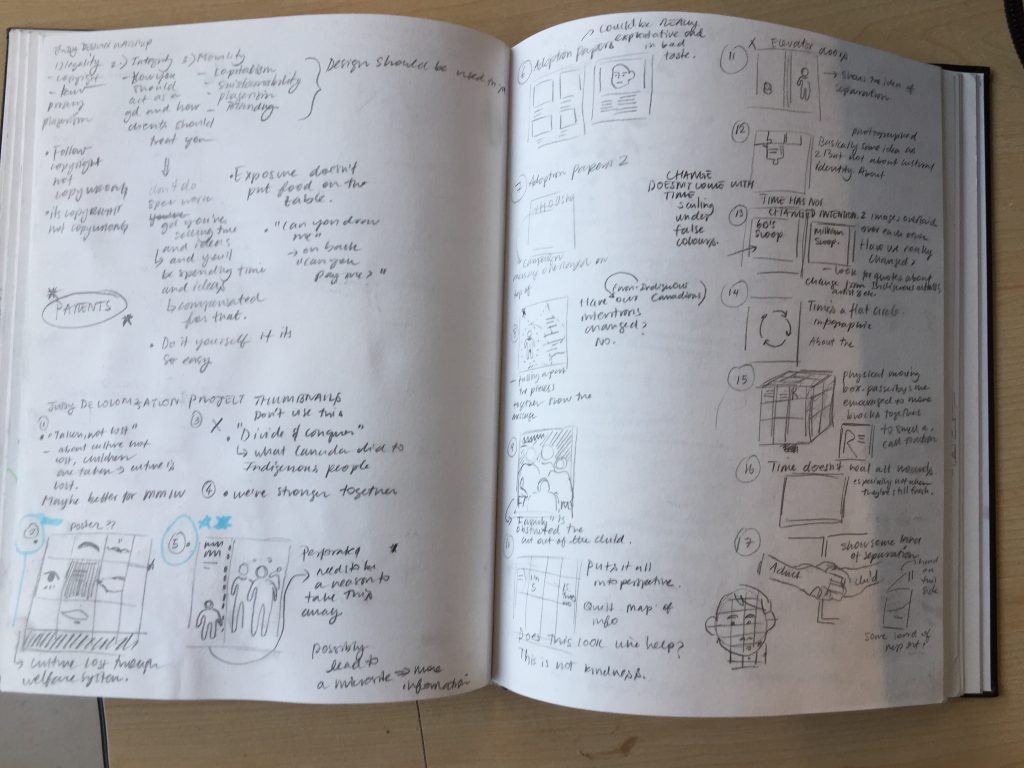

I began the process of picking a topic by reading the Calls to Action of Truth and Reconciliation, where I was intrigued by the inclusion of child welfare. Admittedly, I hadn’t actually considered the role of the child welfare system in systematic colonization, probably in part due to the tone surrounding the entire issue. To be more specific, I had always seen the separation of Indigenous families framed as a perhaps regrettable, but necessary act. However, upon the barest research, that whole idea comes into question, especially when looking at Canada’s history with the subject.

I thought that an awareness campaign targeting non-Indigenous Canadians, specifically parents, would be a good idea. However, I wanted to specifically encourage non-Indigenous Canadians to pressure the Government to enact some for tangible change of Indigenous families.

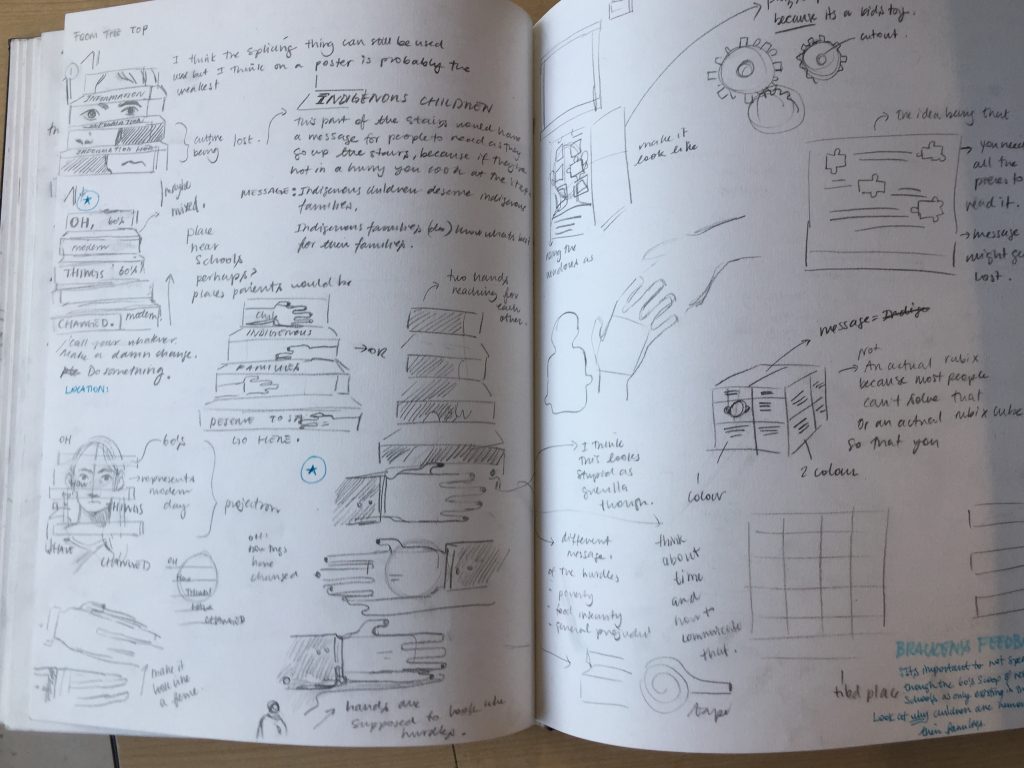

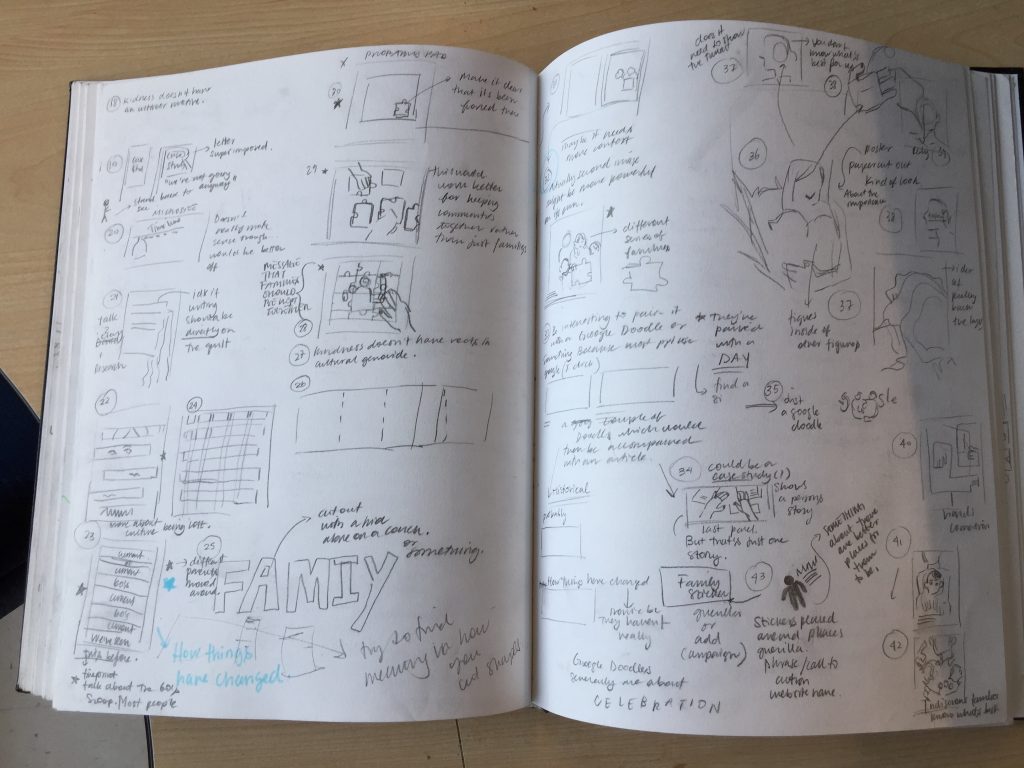

And thus, I began ideating!

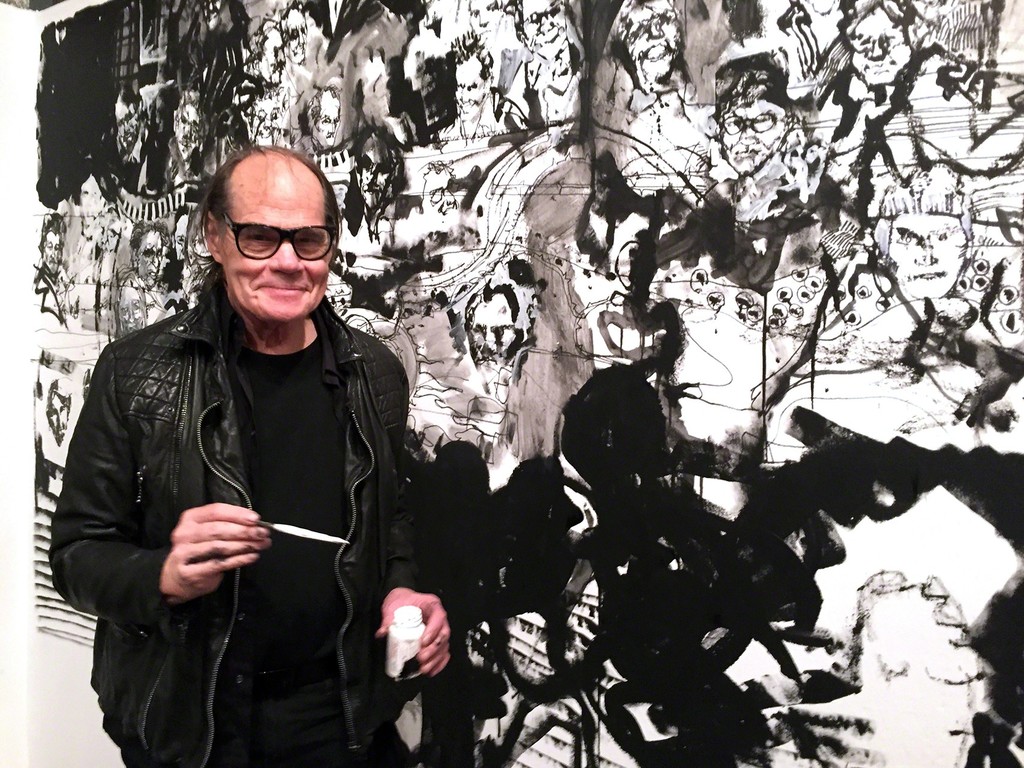

There were a few ideas here that I thought might have potential if carried out further, but I felt that my strongest concept was the idea of splicing images, which I felt could aptly represent some key elements associated with the problem.

Namely, the idea of splicing could represent culture and cultural identity lost through the separation of Indigenous families. This is an especially important idea to express because historically, the eradication of Indigenous cultures and cultural identity was purposeful. It was one of the driving forces behind Residential schools and the sixties scoop. Additionally, many Indigenous families report that this same motive drives much of the current separation of Indigenous families.

Another aspect which the splicing idea neatly expresses is the concept of time. Specifically, it can be used to clearly juxtaposed multiple different periods of time. The juxtaposition creates a system of rhythm and pattern, which establishes the fact that the separation of Indigenous families is a recurring problem.

However, the idea of splicing images is hardly new, and thus I had to find a way to put a new spin on it.

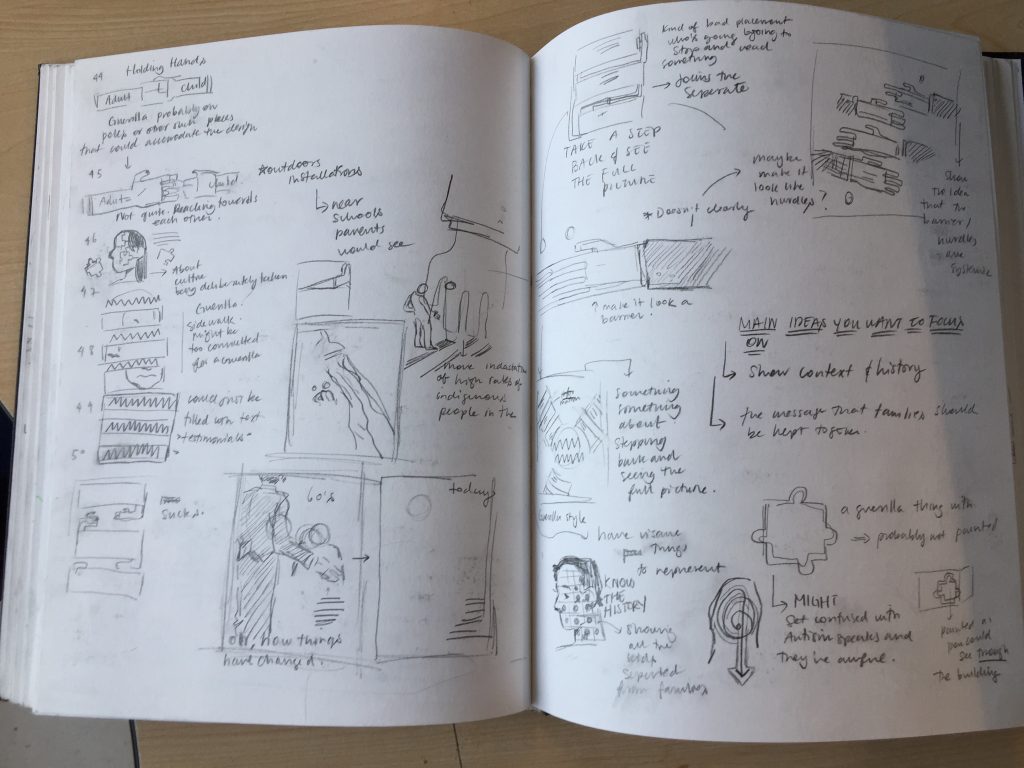

I thought about different ways in which I would apply the images which would strengthen the idea. One of the first ideas I settled on was the idea of using stairs. Ideally, the design would be placed near libraries and other places that parents regularly frequent.

I spoke with others who suggested that my campaign also be included as digital banner adds as well as on bus shelters. After looking at the breakdown of bus shelters, I thought about the natural division in the panels (three in total, two ones on the side and three ) and how I could take advantage of that. I considered breaking it down the center panel into three, and including my message on the side panels. Each panel would represent a different time period and would together they’d read “How Times Change”.

However, I ultimately rejected this idea in favor of spreading the photographs among the three main panels and placing my message underneath the middle panel, which represents the modern-day. I felt like this would emphasize the fact that it is not a problem of the past.

In the end, I think the idea has potential but still needs more work to push the idea further. Additionally, I think that my execution needs much more work and I intend to refine it as my design skills improve. Overall, I would give myself a 7.5/10.