Starting this project, I knew that my views on decolonization and indigenous relations would be vastly different than my target market’s. When talking to my mom about the issue she brought up the inconsistencies in medical care when treating aboriginal children and families, and eventually we landed on the topic of the foster care system.

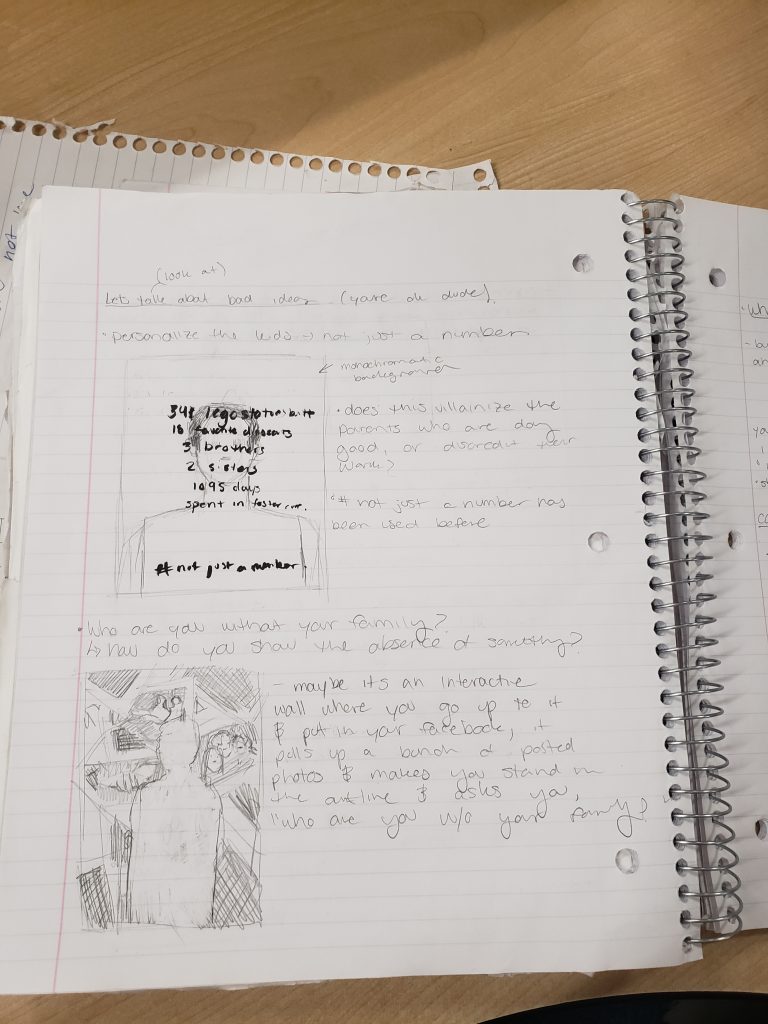

Initially, I wanted to focus on the failure of the government dating back to the Sixties Scoop. I knew I wanted to focus on the individuals to gain empathy from the target market, but I knew I couldn’t call the children broken or incomplete, and at the same time I couldn’t villainize the parents partaking in the foster care system who were providing positive experiences.

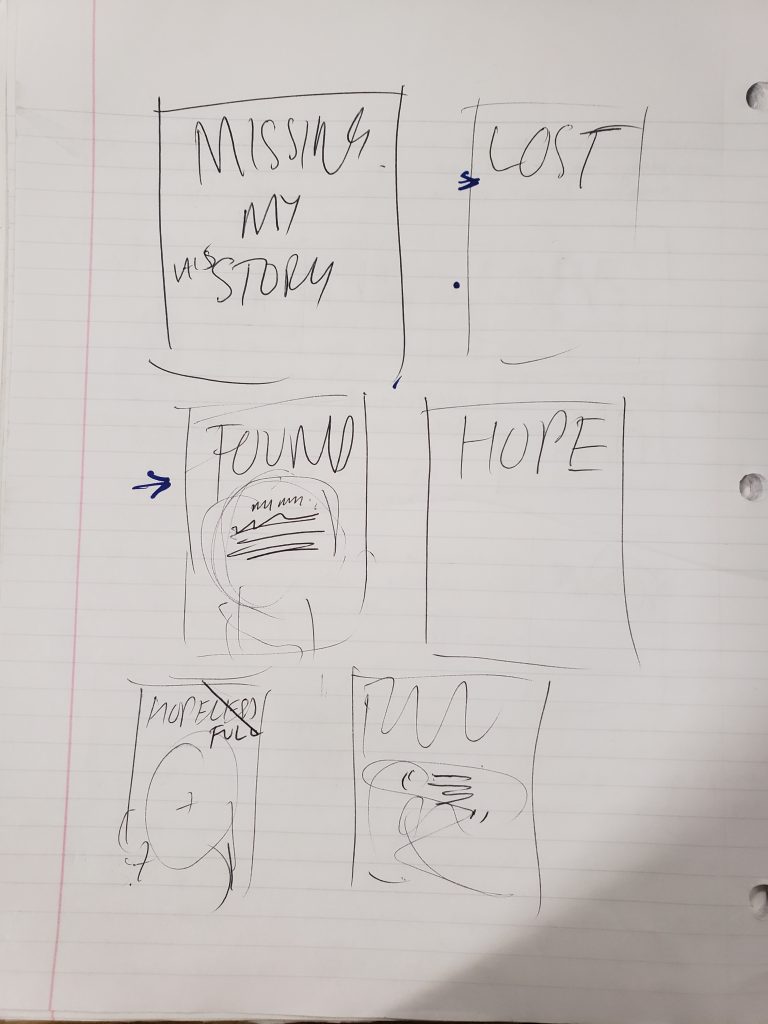

With this in mind, I originally landed on the phrase “Missing But Not Lost,” intended to address the Indigenous identities of the children separated from their communities who’s culture/language/family ties were “missing but not lost,” intending to build awareness for the issue and inspire change in elections. However, this sounded too close to the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women campaigns, and it pointed fingers in the wrong directions. It was through ideation with peers and professors like Vida that landed the idea of the “FOUND” posters. The idea of being found vs. yet to be put the exact positive spin on the campaign that I needed, and gave footing to the funding it needed. Although this removed it from the direct problem (intergenerational trauma and a lack of parenting skills due to the Canadian Government) it re-contextualized the campaign into one of hope and community building, not loss and mourning.

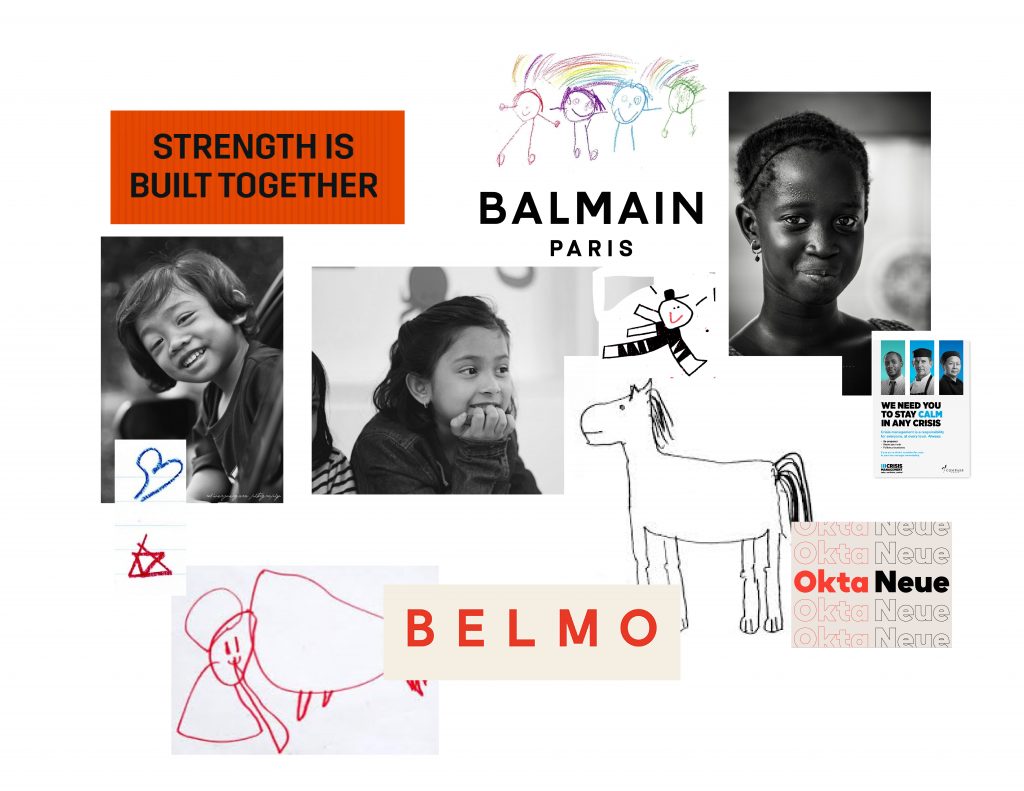

To keep with the positive, youth centred theme I chose to utilize bright colours and children’s illustration. I wanted the posters to be eye catching and dynamic to make them stand out. (See mood boards above.)

I understood that the target market would easily look past a regular poster with a child’s face on it, so I wanted to play to the emotional appeal by showing showing a child in a way that they would want their own to feel. Happy, whole, and inspired. This is also why I decided to incorporate an animated aspect into the campaign, to catch the eye and confront them with an image that seemed alive as opposed to static.

These animations could take form in a number of ways. A short 5 second ad with a simple found logo and link at the bottom, a long form narrated commercial, replacing the photography and illustrations exactly the same as the posters above, an animated card on the website, etc.

I also decided to include a website to provide an opportunity for education and further explanation of the initiative. The first step in removing cultural barriers is always education, allowing the viewer to build sympathy and de-mystifying the other group step by step. At Found.ca, the visuals match that of the poster, and then provides culturally relevant information for each of the illustrations to start educating the viewer in an approachable and comfortable way. Now that you have an emotional tie to the main child shown (Marcus) and you feel like you understand him a little, it explains the reality of the situation lower down the page as to not shock you with it straight away.

Overall, I wanted this campaign to be an approachable, positive way to address, educate on, and fund the very intense process that is rebuilding culture within indigenous youth that have been separated from their communities. The Found project builds up and helps fund organizations that help youth to reconnect with their cultures, languages, communities, and families. These are local youth groups, night-classes for Indigenous languages, Indigenous lead art camps, etc. that contribute to a sustainable community children in foster care would not have had they been without services that the Found project provides.

Self Evaluation

Although I’m happy with my final product, research, and strategy rationale, I think my ideation process and workflow could have been streamlined. I stressed myself out too much in the beginning stages and delayed my working time significantly. In the final product, I am happy with the aesthetic and art direction. I worked very hard on the copyrighting and hierarchy but recognize that there is always room for me to improve in those two areas. If it makes sense, I’d give myself a low A for execution and a B for process.