David Small’s “Stitches” is a groundbreaking graphic novel that directly confronts the effects of childhood trauma. His novel accurately depicts the events of his childhood and how they alter his adult life. Small paints a picture of his home that is silently torn apart by his parents, his own life being disregarded by the people who are supposed to love him most, and most importantly, himself as a young boy as he becomes acutely aware of it all.

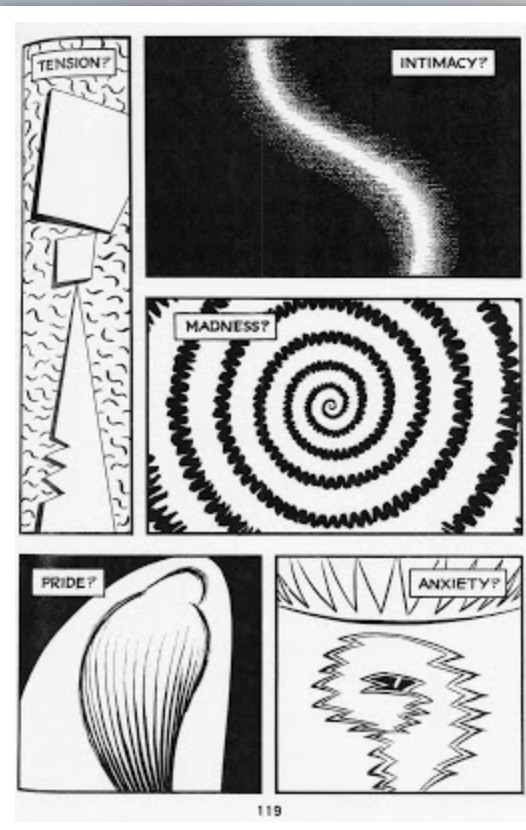

Small uses static, rigid panels to communicate a feeling of stiffness and rigidity. This combined with his moment-moment panel transitions helps to paint an image of a quietly threatening environment. Small’s parents’ desire to maintain normalcy and an unwavering family dynamic can be represented by the seemingly straight but wobby panels that encase each illustration. This subtle technique helps create instability with the reader. Additionally, Small almost entirely assembles his story via moment-moment transitions, a technique which makes his world seem (no pun intended, I promise) small. The childlike perspective helps drive this fact, as David would only perceive what was directly in front of him. Due to these moment to moment transitions we feel as though we are David, turning his head from one side of the room to another to watch the older people talk. When it is not moment to moment, Small separates the viewer from the narrative and into his imagination, or into an external scene to encapsulate an aspect from the previous scene in an abstract idea. However while inside the panels, we often look at Small over the shoulder of another character, emphasising his insignificance as a decision maker in the narrative. As the story descends and we experience moments of height or tension, Small ditches the frame in favor of a full bleed to let the scene consume the reader. However these “consuming” scenes are often pulled far back to help the quiet feeling that persists throughout the story.

Small excellently distills his characters down by only using defining dialogue and cutting out any fat. Our first experience of Small’s Father is all that he did to David when he was younger to help cure his sickness, all that he does to appease David’s mother, but has no defining dialogue attached to him. That is of course, until nearly the end of the book, where he breaks his complacent silence and tells David about his cancer. It truly is as if David’s father doesn’t realize the consequence of any of his actions until he is faced with losing his son. And even then, in the presentation of the information, it seems as though it is only to relieve himself of guilt. On the other hand David’s Mother is introduced through dialogue immediately. By doing this, Small immediately establishes her as the dominant figure in the household. We meet her, in her untiring anger, “Hnf-ing” around the kitchen and making noise to express her displeasure. It is important to note that this develops an important characteristic of his mother from the get-go; she is never direct in her speaking. She will always express her emotions and thoughts in an ambiguous manner. Lastly, we meet David as an emotionally intelligent, ultra perceptive young boy. He picks up on nuances and minute details, even if he does not understand the long term significance of them all. His quiet and private narrative implies he understands more than his parents think. When David does speak at the beginning of the book, it is weak in tone and in conviction. He starts to speak out more as he ages, getting his most brave right before his surgery. Brave for David, that is, as he is still relatively quiet and seemingly complacent. Once gaining his voice back we see David speak more often and with more conviction. It’s as if after being literally silenced (following years of figurative duct-tape having been placed over his mouth by his parents) David feels a new drive to control and define his own life. He starts snapping back, speaking with attitude, yelling at his parents even. His switch in dialogue symbolizes his switch in perspective and awareness of the injustices that happened to him.

The most outstanding use of character development through imagery in Stitches is the author’s illustration—or rather lack thereof—of his parents’ eyes. Small starts the novel off painting his parents as monsters, unemotional people who lack compassion and responsibility for their actions. He withholds from drawing their most expressive part, their eyes, instead illustrating only their glasses. This technique persists until we see them in their weakest or most intense moments. For example, the first time we see the mother’s eyes is when she experiences the same fear that she inflicts upon David while dealing with her deranged mother. As the novel progresses, we start to see the parents eyes more and more as David (and therefore the reader) starts to understand their flaws and view them as more and more human.

The reader learns a lot from visual cues in Stitches, so Small’s use of text is naturally minimal. He spaces out dialogue over panels to make his relationships seem stale and awkward. There’s an emphasis in spaces between dialogue, and only one person gets to speak per panel. This is broken, of course, when there is an argument or someone interrupts another. The majority of the text in the novel is self narrative—showing that Small is telling his story and his story only, and that he is most comfortable with himself as his own closest companion.

Visually, this novel looks like a storm. Most often it is overcast with a slight drizzle (sometimes literally), in its sparse monochromatic black ink washes.. His color treatment is dark but remains looming, with merely the potential to be loud and booming. It’s the great restraint within his treatment that allows Small to pale-down and ground a story that could be ultra-dramatic. This ink wash technique is paired with a line style that is extremely expressive. It is loose and undefined in places and often extremely simple with a very skillfully placed touch of messiness. When asked by Smith Magazine about his technique, he states he likes to stick to the basics. “I drew with a brush and ink, a fine-point nib pen (the kind you dip, gets your hands dirty and splatters you with ink). Except for the lettering—which was done from a font of my own printing, and which lends a nice element of regularity to my loopy line work,” Small comments. He goes on to provide what is possibly the best review of his graphic novel in the phrase “As you see, all very real, tangible, hands-on stuff.” If anything, “real” and “tangible” are in fact the two words that could sum up Stitches. This line style not only lends itself to a child narrator, but also to an unstable environment that is created completely from memory. Where his line style stays consistent, his font usage differs throughout the book depending on intensity, importance, speaker, and volume. For example, when Small’s internal narrative is the focus, the handwritten font is small, thin, and weak, exemplifying Small’s lack of influence and literally weak character within the narrative. When someone is yelling or there are loud noises the font switches to a heavy brush stroke that has a much more bold and abrasive presence. His speech bubbles are often regulated to thin lined semi-stable boxes and do not vary often, which allows a sense of security in the recalling of information. Had Small varied in his speech bubbles, it may have discredited the information, making it seem as a more feeble memory than a confident declaration and retelling.

When we look at the presence of metaphor and symbolism in Stitches the usage is sparse and vague. By far the most overt metaphor is the somewhat out of place visual representation of his therapist as the White Rabbit from Alice in Wonderland. Small’s choice to swap these two characters represents the therapist’s ability to guide Small into his subconscious and enable him to re-interpret his real world surroundings. When asked on the seemingly bizarre choice, Small confidently replies;

“The White Rabbit, in Alice, is the usher into a subconscious world, which Alice sees as nonsense. (She is like a patient rejecting the “curious” evidence of her dreams, which tell her that all is not right in her life.) So, the Rabbit seemed a perfect stand-in for the analyst, who ushers us into the world of the subconscious, where the truth is told at last.”

Additionally, there’s the disturbing fetus that chases David through the hospital halls. It is unclear whether this represents his experiences in hospitals as a young child taking a toll on his body that will haunt him for the rest of his life (the x-rays, the enimas, etc) or his mother’s perspective that David is a nuisance that has ruined her life, endlessly pestering and inconveniencing her since she became pregnant, or something completely different. Regardless of the transparency of the symbol or metaphor, we can assume that these alternate aspects of reality is David—both as a child and as an adult recounting the events while writing—processing his trauma by associating them with extremely unrealistic situations. In an interview with journalist Alex Dueben, Small states “There should be nothing superfluous in the images that take away from the main themes of the story…The reader is the dreamer of a book or, rather, is put in that position, and deserves clarity or, at least, the means to achieve it. And if a dream is going to be included, it should relate somehow to the waking story being told, it should expand that story in a fanciful way, not confuse it for the sake of weirdness.” Although there are certainly parts of the book that are “weird,” they serve no other purpose than to let us into the mind of young David. We may not understand exactly the significance of a drawing of a pit underneath his house with all of his cartoon friends living underneath it, but we do understand the feeling Small wants to communicate.

Through all of these visual and literary devices, Small curates an ultra-realistic experience filled with universal truths. Although all aspects of the novel are not “real” persay, every reader is able to identify with the events and characters in stitches—even if our mother wasn’t exactly an eyeless monster and our life-saving therapist isn’t the exact replica of a much loved Disney character. More importantly Small’s development of his own young self as a character has created a unique phenomenon within readers and in the literary community. By articulating his memories and trauma, Small has fostered the image in the mind of the reader of an emotionally intelligent and socially aware young person. Often the reader perceives children in literature as flippant and naive, assuming actions will have no long-term effects on them due to their lack of permanence due to their youth. Too often we see the common trope of the abused child being a simple mention in a story. We assume that once a child is removed from trauma, the trauma stops existing.

Small changes this. By carrying his story all the way to adulthood, even to the grieve-less death of his mother, we understand the long term effects of life in his childhood home and how it continues to shape him deep into his adulthood. His writing shapes a new type of young character. One who sees the world through knowing eyes, and although they might not be able to correctly understand significance, they can still feel and process and repress the same as a grown adult. Most importantly, David paints his own character as unremarkable. He is forgettable, even. By doing this, the reader can assume that although his experiences as a young man are completely unique, David is not. Through the book we begin to understand that David is the ultimate example of a teenager with a complicated home life, and that everyone can fit into his character’s “mold” to some degree. Part of every teen is able to be defined, albeit in small parts, by David Small’s character.

In conclusion, Small has created a novel that perfectly describes childhood trauma. HIs choice to pair storm-like ink washes accompanied by loose linework creates an unstable and ominous quality to the story. His masterful use of text and limited dialogue to distill characters down to their simplest form allows the reader to perceive them as a child would. Additionally, his short paced moment to moment transitions make us feel hyper connected to the character, acting as a pseudo first person perspective. Lastly, due to his raw, almost visceral recounting of his memories we are able to recognize youth both in and out of literature as emotionally intelligent and aware characters.

Sources

“‘A Conversation with Illustrator David Small,” Julia Tindell.” World Literature Today, 27 Feb. 2015, www.worldliteraturetoday.org/2012/march/conversation-illustrator-david-small-julia-tindell.

Abbott, Alysia, and Alysia Abbott. “From Tales of Wonder to Tales of Horror: David Small Dissects Stitches.” Nieman Storyboard, 14 May 2010, niemanstoryboard.org/stories/from-tales-of-wonder-to-tales-of-horror-david-small-dissects-stitches/.

“David Small: Penguin Random House.” PenguinRandomhouse.com, www.penguinrandomhouse.com/authors/28746/david-small.

“Home After Dark by David Small.” Goodreads, Goodreads, 3 Sept. 2019, www.goodreads.com/book/show/43726550-home-after-dark.

“‘I Don’t Mind Scaring Myself’: An Interview with David Small.” “I Don’t Mind Scaring Myself”: An Interview with David Small |, www.tcj.com/i-dont-mind-scaring-myself-an-interview-with-david-small/.

“Interview: David Small, Author of Stitches: Memoirville.” Memoirville RSS, www.smithmag.net/memoirville/2009/10/06/interview-david-small-author-of-stitches/.

Small, David. “Big Think Interview With David Small.” Big Think, Big Think, 8 Feb. 2019, bigthink.com/videos/big-think-interview-with-david-small.

“Stitches (Book).” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 11 Dec. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stitches_(book).

Weldon, Glen. “’Stitches’ Draws On An Artist’s Painful Childhood.” NPR, NPR, 15 Sept. 2009, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=112842179.