Lecture Review

Todays lecture covered the year zero the year 1450 CE. We focused on the evolution of print and text, as well as the illuminated manuscript and the evolution of paper. Some key titles are…

- Parchment

- Codex and Codeci

- Uncials and Half-uncials

- The effects of Barbaric invasions

- Gothic text and international influence of text

- The Printing Press (Bi Sheng, China)

- The Printing Press (Johan Gutenberg)

I found this lecture particularly interesting. It was fascinating to find out how innovations in text and print were reflected all throughout the known world. Especially in the instances of Sheng and Gutenberg, where they came up with the exact same technology with zero communication whatsoever.

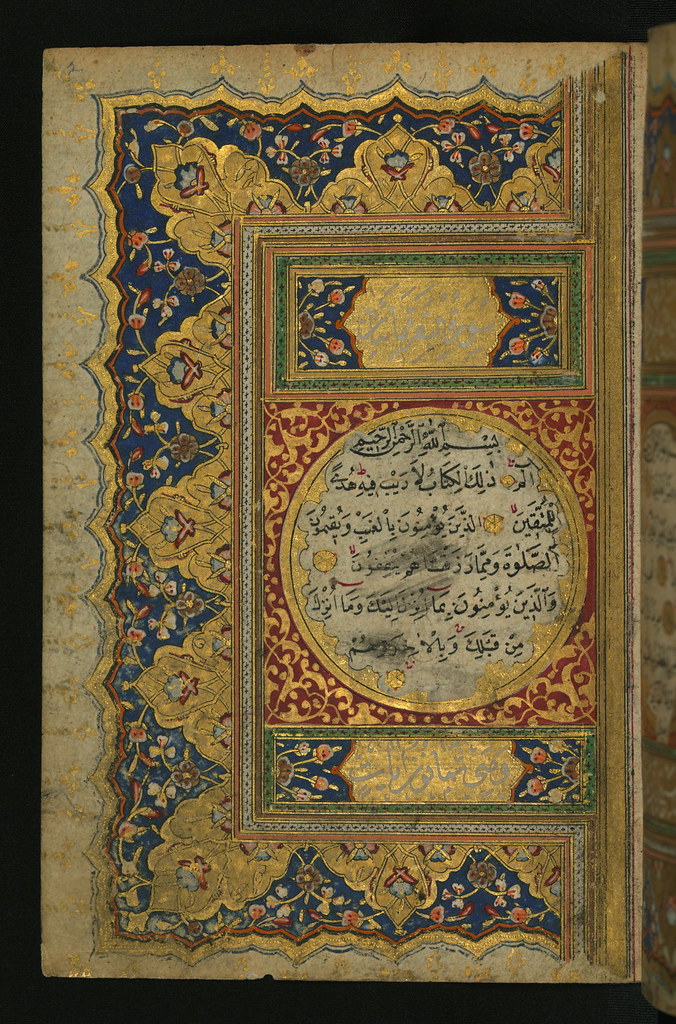

Middle Eastern Illuminated Manuscripts

Illuminated manuscripts of the middle east provided a wide arrange of topics and information, straying far from the typical religious text found in the West. Islamic illuminators were unable to depict humans. The Islamic faith did not allow any renderings of God’s creations with souls, and the lack of such set these manuscripts apart from their European counterparts. People and animals (anything with a soul) were strictly banned from being depicted. All illustrated codecis of the area instead featured natural details, but the majority of the illustrations consisted of embellished designs. The style these books were created in was highly decorative, ornate, and detailed. Artists would work on a commission for months or even years, working primarily in royal workshops with an array of other workers.

In early production the majority of commissioned manuscripts were Qur’ans, religious texts of the Islamic faith. Illuminators would work with the scribes to create elaborate texts to lead the faithful by God’s word. After the scribes produced and decorated the paper, the illuminators would create their inks. Different inks were made up of various minerals, both for colour and for pigmentation.

- Gold

- Silver

- Lapis lazuli/Indigo (dark blue) and azurite (light blue)

- Orpient (for yellow) and malachite (for green)

- Cinnabar (for red)

Ink was first mixed with a glue-like substance called albumen. This made the ink dry glossy, and it was not until the 16th century that artists switched over to a matt texture. This was achieved with gum arabic, sap derived from the acacia tree. The artist would then create a rough draft. This would be achieved with a fine layer of light ink or by using a device called a pounce. To pounce, the artist would lay a transparent layer over the rough draft and prick holes around every outline. Then, they would lay it over the new paper and pound a cloth bag of pigment into the holes, creating an outline where the paper once was. This technique would continue to be used into the high renaissance by muralists and fresco painters. Multiple artist were a part of the drawing process, with junior artists filling in large portions and blocks of colour. After each page was completed, illuminators would add finishing touches. These ranged from gold leaf accents to chapter headings and initials. The very last step would be to burnish the page with a rock of glass stone.

- All the different minerals used to create the ink colours. On the bottom, we see Lapus Lazuli (right) and Azurite (left). On the left of the second row we see Orpient and Malachite.

An Illuminated Qur’an

- Here we have the left side of an illuminated manuscript Qur’an. It was done in 1282 CE, by the Turkish Scribe Muhammad ibn Mustafa İzmir’i. We can see the ornate drawings, gold leaf embellishment, and just how much the different pigments stand out against one another.

Sources:

https://www.library.yale.edu/neareast/exhibitions/exhibit20071.html

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/isbk/hd_isbk.htm

Photos:

Left side of the Qu’ran: