Survey 4 Summary: Steam and the Speed of Light

This weeks lecture mainly focused on the innovations of the industrial revolution and their contributions to the phenomenon of mass production. We began by touching on the French revolution, world exploration and a changing political climate with the crowning of Napoleon Bonaparte. During the “long 18th century” we see climbing literacy rates, a call for reformed social structure, and as mentioned, and increase in mass production. One of the most commonly produced items was books, with approximately 600 being produced in the crowning year of Queen Victoria. There were several machines that allowed this level of production, like the invention of the Steam Engine (invented by James Watt), lithography (Alois Senefelder), chromolithography, or printing in color (invented by Godfrey Anglemon) as well as several new typefaces used specifically for consumer benefit. These included the first modern typeface Didot, Robert Thornes Fat-faces, and Vincent Figgins Egyptian. All were used to advertise to the middle class consumer. We also discussed the invention of Braille, as well as the Joseph Nieps first photographs using the Heliogravure. Lastly, we touched on the Japanese art form of Ukiyo-e, a minimalistic impressionist style that focused on the entertainment district of Japan. My interests during this lecture primarily lie in the typefaces and Ukiyo-e, due to the secrecy of the latter and the matter in which it was transported to the US. The fact that the artform inspired the movement of Japan-ism and Impressionism was astounding to me. I was blown away that these pieces of art that were valued very little in their own society could have such a profound impact on the Western world.

The Quality of Bookmaking During the Industrial Revolution

It’s hard to imagine that at one time books were once a high class luxury item. Now we see cheap copies of paperbacks almost anywhere. Books inhabit every retail environment, whether it be gas station comics or questionable grocery store romance novels, they’re more than easily attainable today. To make things easier, Canada has a staggering literacy rate of 99%, meaning that even if people don’t necessarily want to buy books, there is nothing stoping them from being able to do so.

The industrial revolution saw a vastly different environment. The average literacy rate throughout Europe was an approximate 50% in the year 1800, with the majority of said statistic consisting of white Englishmen. However, this number was growing throughout Europe, and quickly. This increased demand for books called for a faster method of production, cheaper materials, and ideally, less man power.

Prior to the industrial revolution, books were hand-made, bound in leather, printed on parchment or vellum (high quality calf skin), and hand painted often with precious mineral inks and with gold.

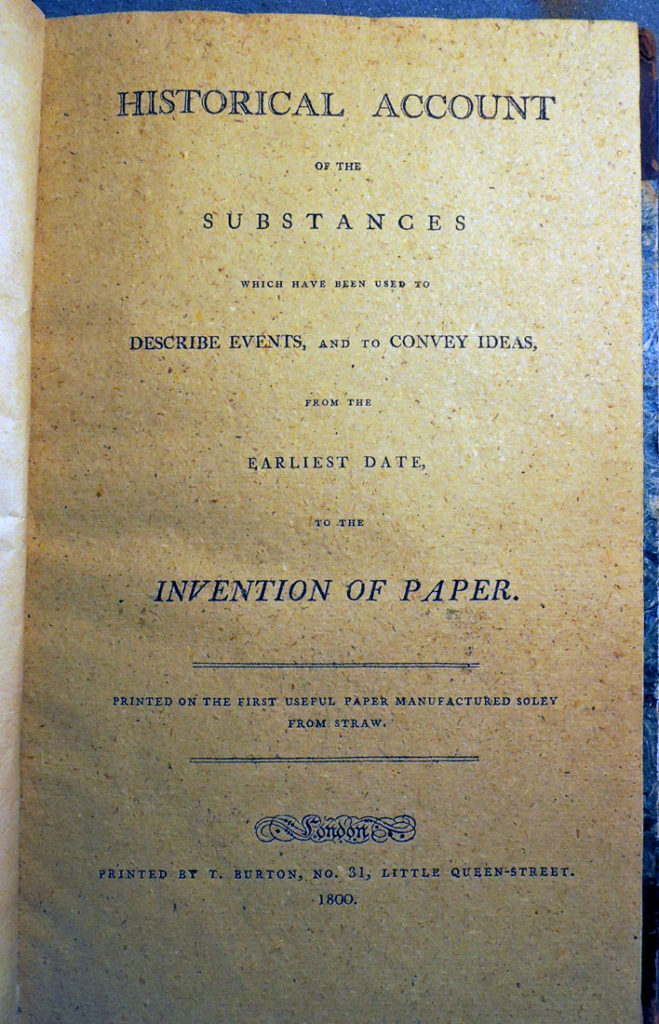

With the invention of the steam engine (done by James Watt in 1765) books were able to be mass produced with significantly less man power. Bookbinders also found many ways to cut costs as the century went on to make the product more consumer friendly and to satisfy the expanding demand. The first cost-cut was in the paper. Vellum was unsustainable and very expensive, so there was a desperate search for an easier alternative. At first paper was switched over to a linen, cotton, or hemp base. This was called “rag” paper. However, as with any product in high demand, the price rose quickly and there was once again a search for more. It was not until the latter half of the 19th century that “modern” paper was created. As stated by www.ibookbinding.com:

“It was not until the 1840s that the initial development of the papermaking machine in England and experiments in ground wood pulping in Germany and Nova Scotia enabled the commercial production of paper, which used wood fibre as part of its composition”

In addition to paper, bookbinders found many other ways to make production cheaper and easier. Leather covers were replaced by starch cloth and cardboard, and were decorated less and less. Cloth tapes replaced the former chords or vellum strips formerly used in the sewing process. The bookbinder would also apply a false band to create the authentic handmade feel. The invention of chromolithography aided in lowering the cost and employee count by getting rid of the need for hand painted illustrations, as did the invention of the sewing machine in 1832 by Phillip Watt. This enabled companies to sew in bindings, instead of doing it by hand. Bookbinding could now be done by the publishers themselves, eliminating another middleman. In 1860, machinists (those who would be working the printing presses and binding machine) would be making an approximate weekly wage of $10.00 a week for 60 hours. Eliminating more employees brought down the cost even further, approximately $520 a year per employee.

So if the quality changed…shouldn’t the price?

Mass production enabled books to become a commonplace object in Europe during the industrial revolution. In fact, from the years 1450-1800 there were 1 726 166 total books produced, with a staggering 641 166 of those being produced in the last half of the 18th century. In the mid 18th century, illustrated books that were short in length cost an average 3 dollars, with custom and luxurious books being much more. 3 dollars in the 18th century was enough to buy food for 1 family for 1 week. Now, the average American family of four spends an average of $239 a week for food. Compared to the prior cost of books (handmade books could cost the same as a farm), 1 week of food was much more affordable.

Sources:

https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/museum-life/tradition-and-transformation-in-19th-century-bookbindinghttps://www.ibookbinding.com/blog/bookbinding-history-and-introduction/https://ariettarichmond.com/paper-early-1800s/https://historyofinformation.com/expanded.php?id=500https://www.officialdata.org/1800-dollars-in-2018?amount=0.15https://hlq.pennpress.org/media/34098/hlq-774_p373_hume.pdfhttps://knoema.com/atlas/Canada/topics/Education/Literacy/Adult-literacy-ratehttps://www.quora.com/How-many-people-could-read-in-1800s-Europehttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_steam_enginhttp://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/historicalbookarts/id/986/rec/5http://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/historicalbookarts/id/994/rec/1https://www.google.ca/url?sa=i&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=images&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjS99GM4__dAhX6HjQIHbOlB7sQjRx6BAgBEAU&url=https%3A%2F%2Fen.wikipedia.org%2Fwiki%2FMainz_Psalter&psig=AOvVaw1t6RGoDy6HQJdiJLgjaH_M&ust=1539394902290523https://www.bookstellyouwhy.com/advSearchResults.php?action=search&orderBy=relevance&category_id=0&keywordsField=vellumhttp://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/cdm/singleitem/collection/historicalbookarts/id/994/rec/1